[This is the second part of an ongoing series. To read more, see Part 1 here.]

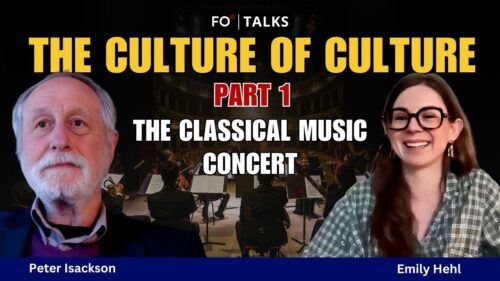

Peter Isackson: Welcome to FO° Talks. I’m Peter Isackson, Fair Observer’s Chief Strategy Officer. It’s my great pleasure to welcome back the talented opera and theater director Emily Hehl for our second edition of a series of conversations we’re calling The Culture of Culture. Our focus is on music, theater and all forms of storytelling. A key aim of what we’re doing is to look more deeply into the role of the audience — not just the artist, but the audience. Now, in the previous chat, Emily, we talked about the history of the classical concert and the role of the audience in its construction and impact. Today, I think you suggested that we delve into the relationship between music and storytelling. Could you just say a few words about what you’re working on now in Vienna?

Emily Hehl: Yes, I’m currently working on two productions, one of them being a new production of Norma by Vincenzo Bellini, and the other production is something that will be coming later this year, which is a new opera about Lee Miller, the war photographer who took a picture of herself in Hitler’s bathtub. And this new opera is questioning how a person could possibly have the idea to take a picture of herself in Hitler’s bathtub, and therefore it becomes a very intense portrait of Lee Miller and things she lived through. And yeah, so that’s the things I’m currently working on. And then, yeah, I have the pleasure of having these serious conversations with you every few weeks, which is a big pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Peter Isackson: Oh, it’s a wonderful pleasure for me to have these conversations. I never know where they’re going to go.

Emily Hehl: Neither do I! (Laughs)

Historical context and rediscovery of La Montagna Noire

Peter Isackson: So it’s not like we’re talking about the events in the political world — and there are plenty of those today — but it’s great to get away from them. So let’s go look at La Montagne Noire, which I don’t think many people know. It had some impact at the time. I think it was noticed by the musical world in Paris, where it was produced. When was it? Just before the end of the 20th century?

Emily Hehl: Yes. So the world premiere was 1895, and it was written by Augusta Holmès — a woman. She was French-Irish, and it was only the second opera that was ever premiered by a female composer in the Palais Garnier, or the big opera house in Paris. And the one before had been Louise Bertin in the 1830s. So after 60 years of no female composers presenting their own works in Paris, this was only the second time in history. So for that reason, this was quite remarkable, but it was forgotten since then and never performed again since 1895. And so we re-premiered the work last year at the opera in Dortmund in Germany.

Peter Isackson: So, has it been forgotten or neglected because it was written by a woman? She was the composer and the lyricist at the same time?

Emily Hehl: Absolutely.

Peter Isackson: And I think the critics said that the music was really good and interesting, but the plot and the writing wasn’t up to the same standard. Was that your impression?

Emily Hehl: To me, it would be the other way around, because I think the libretto is remarkable. But you’re right — she wrote the libretto herself. She wrote poems, she was composing, she was singing as well. And at her time, she was one of the most famous women in France, and she was living a radical life. She had kids with a man she was not together — who was actually married with someone else. So she had really the most liberal life you could imagine at that time. And being a composer as a woman in France, who actually had an Irish nationality, was very, very difficult for several reasons. And why was this work forgotten? I think, yes, her being a woman might have been one of the reasons, because the critiques were worse than they might have been if it was a work by a man at that time. But also, I think we’re quite deep in the kind of content we want to talk about, which is, for example, the repertoire — and how do things become part of history, and how do things just disappear in history? And I think it’s the responsibility of the people who live after the composers to keep these pieces alive. Because, I mean, many composers like Bach and Mozart, they were not composing music for them to become eternal. Music was composed for one event, usually. The idea of repertoire is an invention. It was not usual. But there was this time where an audience and performers started going back into history. And then, of course, we started appreciating a certain quality of pieces and then seeing pieces which are not in this kind of canon or repertoire. Sometimes they might have less quality, but also they might remind us of the quality that the pieces have that we keep playing again and again. So I think there’s a whole question connected to why do we not play certain pieces.

Emily’s directorial approach

Peter Isackson: So was this your choice, La Montagne Noire? And how did you — or whoever made the decision to produce it — how did you come to know it, because it’s such an obscure part of the repertoire?

Emily Hehl: It is. No, the artistic director of Opera Dortmund asked me if I would like to do this piece. The piano reduction was available on the Internet, and it is a collaboration with the Bru Zane, which is an edition that takes care of rediscovering composers or preparing the material in order for these works to be played again. And so they invited me, and all I got was the score. There was no translation, there was no research on this piece very much. And that’s a very different approach to directing, because usually, if you direct, I don’t know, an opera by Puccini or Verdi, you have to, on the one hand, deal with the piece, but you mainly have to deal with the history of the performance, because what has been done? What have been the interpretations? How have people looked at the piece? Whereas in this case, it was really just about trying to get any information about where is the libretto coming from? Because she wrote it, but you felt that there were sources. What is all of this music? Who is Augusta Holmès? So it was really more of a scientific work for a long, long time. It took me almost three years to prepare it. And I translated the libretto myself, all these kinds of things. It was really research. But it was beautiful. I play the piano, so that was very helpful, because whenever you turn a page, I started playing, and it was like reading a very interesting novel, because you had no idea where it would go.

Themes and storytelling in La Montagna Noire

Emily Hehl: And so, yeah, I did a lot of research on the libretto. It’s set in La Montagne Noire — it’s an old French word for Montenegro. So it’s set in this Slavic country during the time of the Ottoman occupation. And you feel in the libretto that there’s a lot of very specific terms and words that I didn’t know, but it didn’t feel as if it was a pure fictional text. And so I started doing a lot of research, and I was diving into the folk songs of the Slavic time around the time where the story is set, because often diving into folk poetry and folk songs can give you a lot of ideas of where things might be coming from. And as I was reading these folk songs of the Slavic people of this time, I recognized a lot of parallels to this libretto. And it turned out that she must have known these folk songs, because around the time where she was writing, just a few years before, there was a French translation of the most famous Slavic folk songs published in France. And she most likely came across them, because her father had one of the biggest libraries of France at the time. And it turns out that she must have done some kind of a mosaic — taking characters from the Slavic folk songs, turning them into a different kind of story, but also uncovering the backside of all the heroes and myths, and basically showing how history and myths are being constructed. And that maybe the truth is not the most strong word for where these stories are coming from.

Peter Isackson: So that’s why you maintain that the libretto is more interesting than the music itself?

Emily Hehl: Absolutely. Also because she talks about constructing, the construction of history, not knowing that she would be the one being forgotten. I mean, she had no idea that this could happen. But looking at it from today, her caring so much about her heritage and talking about how people are being remembered and then being forgotten herself is quite a remarkable combination of things. So we made this whole reflection part of the production. So, yeah.

Peter Isackson: I take it that when you were asked to do this — I don’t know if you committed immediately — but you didn’t know what you were getting into?

Emily Hehl: I had no idea. I was young. I just took it. (Laughs) Honestly, it was the first — I’m quite young, and I’m very lucky that at an early age I had people who trusted me to direct these kinds of massive operas. The whole thing is over three and a half hours. There’s a massive chorus. There’s like a hundred people on stage. The orchestra is almost bigger than Wagner’s orchestras are. It was a massive undertaking. So when they offered it to me, of course I was very much afraid. But yeah, I had no idea what would come.

Peter Isackson: How do you work with the performers? Are you concentrating on the musical side or the textual side — the storytelling side — or both?

Emily Hehl: Both. For me, I always start from music, because I’m a musician at first, and that’s ultimately what singers are as well. You can never go against the music. You always have to deal with the fact that it’s singing people on a stage. And there was a time of directing where directors tried to hide that people were singing — they should act as if they were just in a movie. But it doesn’t work, because singing needs your whole body in order to do it. So that’s where I will always start from, is this whole physicality of singing. But then, of course, in a case like this, to really have everyone included in the whole development of the piece and where things are coming from is important. So what I did with this production was that the first day — which is with the whole cast sat on a table — I tried to tell them everything I had researched in the last two and a half years. And it’s important for people to know where characters are coming from, because especially in this case, most of the characters have an equivalence in the Slavic folk culture. And so we were preparing, kind of — they were reading into the songs and into the characters where their characters were based on — because it’s important for a singer, an artist, a performer, to know where their characters are coming from. But in this case, we also invited a Montenegrin-Serbian artist whose profession is to sing these folk songs. So there’s this very specific instrument called the gusle, which is a one-stringed instrument, and it’s played like this. And this is how the bards at that time were traveling through the countries singing these folk songs. And because this is where this story is originating from, we invited a female artist from Montenegro-Serbia — she’s half-half — and she was part of this production. And we basically looked at the piece of Holmès through her eyes — or actually through her blind eyes, because we had her as a blind character. And so the audience was diving into the imagination of this blind bard. And that’s how the opera came into existence for the audience.

Audience reaction and impact of political events

Emily Hehl: Because it’s also a difficult piece — 1895 — I mean, political correctness is not the term that is the right one for this piece. So there’s a lot of religious conflict. So you have to be quite clever and careful when putting something like this on the stage, to not reproduce any kind of conflicts or assumptions or these kinds of things. So that’s why we chose this blind, imaginational approach to look at the story.

Peter Isackson: So when you started working on it — you say it took three years.

Emily Hehl: It took three and a half years, yeah.

Peter Isackson: So that was before the political events that Eastern Europe has been living through. Now, did that have an effect on the audience and on the production itself? Because, I mean, this is about the Balkans. The Balkans is the frontier between Eastern and Western Europe. In some ways, it epitomizes what’s happened in Ukraine, right? I just throw that out. I don’t want to get involved in political discussion, but your experience as a director and part of a production that wasn’t designed initially to take into account the politics that was going on around you. Of course, you did it in Dortmund — you didn’t do it in Montenegro. But just tell me if that had any influence at all, negative, positive or interesting, let’s say.

Emily Hehl: I mean, of course, it always has an influence, because you read the news in the morning before you go to rehearsal. So you’re full of these conflicts and these themes. But then also, you have to take artistic, visual decisions two years in advance, so you never have an idea what will be happening when you actually are directing the opera. Which is one of the reasons why I try to very much avoid any kind of contemporary reflections on a stage visually. Because you will always be behind, you have no chance. And therefore I’m trying to, of course, create a universe on a stage that allows these kinds of reflections, but they are never explicit. But of course, you know that the audience will be loaded with this information, and they will look at certain conflicts in the opera differently than you would have probably imagined they would a year before. But I think, therefore, it’s a task of an artistic team and the director to keep this openness without being too explicit, and to avoid making something too small. Because you have to be very concrete when you do something on a stage, otherwise no one can act if you don’t have a very concrete situation. But you can also not make the situation too concrete and too small, in order to keep the openness and the reflection of the audience into this situation.

Peter Isackson: So in terms of your aesthetic choices, as you were saying earlier, some people try to contemporize — if we can say that — to bring up to date traditional operas where the plots took place in defined historical circumstances, and then bring them up to date by referring to either modern customs or modern events and modern costumes as well. I think you chose a more classical idea of using the costumes and the styles of the end of the 19th century. Is that right? Or was it set in an earlier time?

Emily Hehl: No. So what we did actually is — because it’s so difficult, especially with these kinds of politics and these kinds of conflicts — to actually reproduce something on the stage. And therefore the approach we chose was through this blind poet. And maybe I’ll just quickly dive into why we chose this: Because I told you that this libretto comes from these folk songs, and that’s the reason why I suggested this theme for our conversation today — because there’s so much more connected to it than just this opera. Because there were these bards traveling through the Slavic countries, and they were writing their songs, and they were listening to people — their stories, their opinions on historical events — and they turned this mixture of historical events and fiction into the songs. But the interesting thing is that many, many of these bards were blind. So they had no possibility to verify things with their eyes. But they were really just depending on what people would tell them. But then these songs were the kind of historiography of this country at that time, and the people were singing these songs as kind of marching into the vision which they had created in the songs — they wanted to be freed from the Ottoman Empire. And they wrote songs about this liberation. But so historical events were turned into songs, and these songs then were turned into historical events, because eventually they were freed from the Ottomans. And so this kind of circle — how stories and fiction influence historical events, and how historical events are always stories in the end, because it’s what we tell each other — that was very crucial for us. And this idea of blindness, in a very beautiful, poetic sense, was the starting point for our production. And therefore, what you see on the stage is neither historical nor purely fictional, but we actually took fragments from all kinds of times and we turned them into a fictional world. Because Augusta Holmès, she had never — at least it’s not recorded — been to Montenegro or Serbia. She had no idea what it looked like. So she described certain things, but it’s a very French look of the 19th century on these kinds of things. And so we didn’t try to make a documentary, but we were really trying to go into this individual imagination of a person imagining these stories and these conflicts.

Peter Isackson: Were you thinking of a parallel with Homer? Because isn’t that the story of how the first truly important literature of Europe is accounted for? Whether it’s true or not, whether Homer was actually a blind poet. I mean, I think historians believe that there were a whole series of poets who were Homer, but maybe all of them were blind or some of them were blind in the same way you say that that seemed to be part of a tradition in the Balkans.

Emily Hehl: Yes, absolutely. It’s very, very fascinating. And this idea of this blind historiography that we’re now talking about — Augusta Holmès — and that’s why I think the libretto is better than the music, up to a certain point, because we have these myths in the Slavic culture. One of them is about Marko Kraljević, who is now — and I was in Montenegro in summer to really see the kind of settings and to talk to people — the hero of the Serbians, I mean, what we call Serbia now, because he’s the most celebrated hero who freed the country from the Ottomans. But if you dive deeper into the research of the historical Marko Kraljević, he in the end actually switched sides to the Ottomans. He didn’t die in the battle, but he had a quite good life until the very end. And so the main character in the opera is not called Marko but Mirko, but his fiancée has the same name. So it’s very obvious that she refers to this very character. But what Augusta Holmès does in the opera is that she uncovers the point where he actually switches his sides. So in the beginning, we have the folk and the people who are telling these songs about the hero, but then the audience — and that’s the interesting point — witnesses the actual other side of the coin of this myth. But in the end, the people keep singing the same song as they did in the beginning, but the audience knows more than they did in the first act. And in the very end, it’s very much about who survives and who is dying — because the people who survive, they will be the ones telling the stories. And that’s where we are questioning: Why do we perform certain pieces and why do we forget others? It’s always our responsibility — the living — to transfer stories in written or oral ways and to keep performing pieces. Yeah, it’s our responsibility.

Peter Isackson: So you added — I mean, as a jazz musician, I would call that your act of improvisation. You added the blind poet. That’s quite a feat, because you’ve got an opera which is totally composed. Did the blind poet actually have a musical role in your production?

Emily Hehl: Yes, but it was not part of the score that she wrote — something we added. But it was, for me, very, very important to actually add it. Because if you look at music in the 19th century, you have a lot of this local color — it’s composers who tried to make music sound like something they imagined Egyptian music would sound like, or Serbian music would sound like. And in order to overcome this, and to just say, okay, you see, this is an actual heritage of this country, and this is what Holmès made of it — but this is not trying to be this. This is really — it’s the creation of poetry, it’s fiction. It’s not reality. And also, for me, talking about this whole culture, which is a very complex culture — when I was in Montenegro this summer talking about these stories — it’s so deeply rooted, these conflicts, until this very day. And so for me, it was very, very important to have someone from this culture with us in the production to verify things and to feel more comfortable with this theme and to tell this story — which is definitely not my story — but to actually have someone on the stage who cared about it very, very much, because her grandfather had already been one of these blind poets as well. It felt more acceptable for me to perform this piece or to direct this piece, because I felt there was some kind of justification for it on a stage. And yeah, people said that she really opened their eyes for a different form of singing also. Yeah.

Peter Isackson: I’m very interested — you’re in the audience reaction. I mean, how much feedback do you get from your audience, and how long did the production run?

Emily Hehl: We had, I think, six performances, but spread over several months. And so, I mean, you get as much feedback as you would like to take in, because everyone will put their opinion on you if you want or not, but it’s up to you to listen to it or to actively seek for it. But the interesting thing was that there were some people at the premiere, and they kept coming back for every single performance because they loved the music, they loved the piece, and they loved the production. So if a theater programs a piece like this, they know that it won’t be sold out, because it’s not Don Giovanni and it’s not Wagner. But of course, then therefore they do musical theater before to be able to finance this kind of responsibilities, experiments, whatever you want to call it, rediscoveries. But the people who were there — and I was in three out of the six performances, for other reasons I was in town — but so I witnessed three of the six performances, and the audience was cheering and really, really enjoying the performance, apparently. Of course, you always have people who don’t like anything, but in general, the reviews were good and the audience seemed to really enjoy it as well.

Comparison with other productions and personal reflections

Peter Isackson: Because the storytelling was such a big part of it for you, do you feel that the audience could appreciate that and had learned something, if you like, had challenged their understanding of the opera itself? I don’t think that’s really a question, because nobody knew the opera — it’s not like Don Giovanni or Norma. But do you feel that you got the point across, the original points you were trying to make about the history, about the story itself, the impact? Also, it’s a tragedy, right?

Emily Hehl: Yes, it is.

Peter Isackson: So it’s got that emotional dimension which fits into a historical context. So you could look at it like any Shakespearean tragedy and say it’s as much the emotion as the poetry and the music. But I’m curious: With only six performances, what kind of feedback do you get? I suppose there were critics about it.

Emily Hehl: Yes, and we also got nominated. There is the International Opera Awards, which is one of the biggest awards for opera. And our production got nominated for the Best Rediscovered Work. So it was really appreciated in the critics and the reviews. Also, what I was happy about most was that people were interested in Augusta Holmès and not only in this Slavic culture, because they were really intrigued by Bojana Peković. That was the artist that joined us. And she was also giving workshops around and concerts and stuff. So I really think that the people who saw it were really, really touched by her singing as well, because it’s a very different way of singing. It’s very direct. If you know this kind of wide voice that just goes right through your body — you immediately get goosebumps. It’s the opposite of operatic singing. Also to have this as a contrast, I think for audiences this was a great experience. But we had a lot of after-talks and these kinds of things. And people were just curious about Augusta Holmès. Because when you read a little bit about her, you wonder why you had never heard about her. Because she was so big at her time. Like, she was a friend of Wagner, and she had relations with Liszt and a lot of really important composers. She was very deeply in the scene of the poets in France at that time. Everybody knew her, but no one knows her today. And so I think that’s what people really started to wonder about — how is this possible? And I think this is where the reflection probably sets in even more than in just the story of the opera. Because her life’s story and the dilemma and drama of her life’s story corresponds so much with what she actually talks about in the opera, without knowing that this would become her story. The question that you are not responsible for what people will tell about you once you’re not on this planet anymore. So I think this was a coincidence of these two things that, yeah, I’m sure people realized it, and I hope that it inspired them to think further into it.

Peter Isackson: So how would you compare the kind of experience it was for you — in terms of the research you did on storytelling itself, and the relationship between music and narrative, and propaganda even, I think, is part of it because there’s this political dimension — how would you compare that with what you’re doing with Norma?

Emily Hehl: It’s a completely different world. It’s literally a different universe. And I must say, I prefer the universe of the rediscovered works, because you feel you’re actually contributing to something. And you’re giving these pieces a chance to be seen again, and also people to experience these things. I had a very interesting conversation with John Andrews not so long ago — who is a British conductor who is a master in performing rediscovered works or works that hadn’t been performed in a long time, or even just in the last 20 years. And as I said in the beginning, for me, it’s really the main difference that, in the case of Holmès, you take care of and really investigate the piece, just the piece and how it came into existence. Whereas in the other case of Norma, you’re mainly busy with what have other people done with the piece. And for me, that’s different.

Peter Isackson: With Norma, do you feel — I mean, not you personally — but is this the normal thing, to feel that you’re in competition with all the directors who have done this before you?

Emily Hehl: Absolutely. Because even now, it’s really culminating, because Vienna has two big opera houses: Staatsoper and Theater an der Wien. And within a few days of difference, they’re performing Norma in two different productions. So this is really the culmination of the problem I’m talking about. Because it’s not about Norma, it’s about the competition of these two productions. And that’s what I really, really admired about being able to direct La Montagne Noire, was to dive into this universe. And yeah, I mean, it’s a beautiful coincidence that this became this kind of meta-reflection on storytelling and historiography and all these kinds of things. And also this historiography that reflects on the repertoire we talk about. And I think that’s a whole other series of serious conversations, is the repertoire and who came up with the idea of having a repertoire, and how it didn’t exist for a very, very long time.

Peter Isackson: Yeah, so just to go back to the question of competition, you are now competing with another production?

Emily Hehl: Yes, Staatsoper is competing with another production! (Laughs)

Peter Isackson: Do you communicate? Do you know the people there?

Emily Hehl: Yes! Well, so the Norma, it’s not my personal direction. I’m part of the team, but it’s not my responsibility what the artistic output will be. There’s communication, there’s non-communication, I would say. Yeah.

Peter Isackson: I mean, when I say that, do you try to do things differently because you know the others are doing it in a certain way and you have to contrast? And is there a spirit of competition, or is it a kind of creative collaboration — “We can both turn Norma into something contemporary with impact on the audience?”

Emily Hehl: Ideally, it will be the second. And ideally, people who see the show in one place are so curious that they want to see the piece in the other one. And also it’s beautiful, because you’re confronted with the core conflict of performing arts, which is: You can never see a piece as it just hangs in a museum. Because you always need the people to do it. So I think this is really a beautiful problem we have, and something we’re presented with or we are confronted with now here in Vienna, on this example of Norma. But then also, something I said before is that you have to take the major decisions many years in advance. And with this size of house, even more than two or three years. And I’m not even sure if back then, things were clear that things would happen at the same time, so I’m quite sure that these productions came into existence without knowing of each other. And so, yeah. But I hope—

Peter Isackson: We’ll kind of wrap this up, because we’ve used the allotted time. But I’d like to come back, in perhaps a more general way, to the question of competition or collaboration in musical productions. I have my own ideas about it, but in a different context. We have the example given to us by Hollywood of Amadeus, where we are told, through that storytelling, that Mozart and Salieri were competing in ways that probably aren’t very true, but maybe they are as well. But that’s a topic — if you’re interested — I’d like to come back to that in one of our conversations.

Emily Hehl: Yes, I’d appreciate that.

Future plans and legacy of La Montagna Noire

Peter Isackson: Okay, great. Well, thank you again. And is there any place that people can profit from your production of La Montagne Noire? Has it been filmed?

Emily Hehl: It has been filmed. It hasn’t been published. But if anyone who is watching this is actually really curious, just reach out to us and I’m sure we can find a way of sharing this recording. But it’s not available in public. So we hope that someone will program this piece again. I mean, that’s why these kinds of awards — one might think about opera awards, whatever you like — but it’s good for these kinds of reasons, that things stay in the memory of people for a bit longer. And so maybe there will be an artistic director who will program it again. There are even conversations of actually bringing the piece to Montenegro, because Montenegro doesn’t really have an opera story. That was the reason why I was there in summer, because we’re trying to find a way to bring the piece there. But then also we would need to majorly rewrite it, because, of course, then there is already a political interest in performing art. And then that’s where it gets difficult for me as a director, because Augusta Holmès — she had never in mind to write it for this kind of event.

Peter Isackson: Yeah, if you were to do it again more than a year later than the initial production, would you have the same singers? Would they be available?

Emily Hehl: It really depends on when and how and what. But it’s also for singers to learn a piece that no one has ever performed before, and that will most likely not be performed again, and then you confront this really difficult music of like three and a half hours. It’s quite an investment of a singer to say, “Yes, I really want to do it.” And usually you don’t have an idea what the piece will be like when you sign the contract. So, yeah. It would be wonderful to keep—

Peter Isackson: At least they can see the film.

Emily Hehl: Exactly. (Laughs)

Peter Isackson: Okay. Well, thank you very much, Emily, and I’m looking forward to our next session. We’ll be announcing it very shortly.

Emily Hehl: Yes, wonderful. Thanks for this invitation to chat.

Peter Isackson: Bye.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment