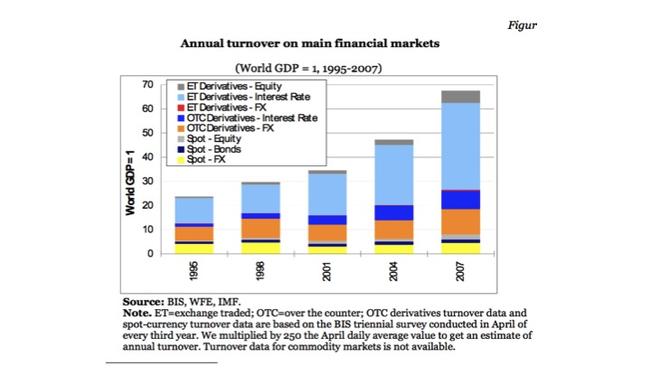

Though the European Union is considering the viability of a Financial Transaction Tax or Tobin tax, it is unlikely to be implemented given the current economic situation. Excerpt from a working paper by Daniel Chorzelski, Lukas Doerfler, Alex Hodbod, and Hannes Timischl, students in the International Trade, Finance, and Development Masters Program at Barcelona GSE. Why Tax Financial Transactions? Financiers have a lot to answer for. As the architects of the ‘structured products’ that turned into ‘toxic assets’, as the funders of those subprime mortgages, and as the recipients of hundreds of billions in taxpayer bailouts during the crisis, they must shoulder some of the blame for the world economic crisis. With anti-banker sentiment reaching fever pitch, politicians and commentators are looking for ways to tame financial market excesses. One of the more interesting of such proposals is the Financial Transaction Tax (FTT), or Tobin tax. Proponents believe it will curb trading that is of dubious social value (e.g., high frequency trading and derivatives activity), while skeptics argue that more targeted interventions might address problems more efficiently. The Financial Transactions Tax has passed through various iterations since it was first suggested in 1936. The most recent proposal from the European Commission calls for a 0.1% tax on the exchange of shares and bonds and 0.01% across derivative contracts. The tax would be levied when one of the trading partners is located within the European Union. The tax does not touch currency trades, which had been considered in earlier versions. Dubious Economic Impacts To assess the European Commission’s proposal for the FTT, we must consider its impact in three areas: its potential to generate government revenue, its likelihood of reducing volatility, and the severity of increased costs of finance. Our opinion is that neither of the first two produces a sufficiently positive impact, and that the latter is a considerable drawback. Generating revenue The EU’s €57bn estimate is based on a tax on a very broad range of transactions, and involves contentious assumptions about the elasticity of demand for transactions, and the behavioral response of economic agents (who may relocate transactions in order to avoid the tax). In our view, the estimate is on the high side of what could be extracted, and we see huge political economy problems generated by the uneven geographical distribution of revenue creation from the tax as proposed (with the majority coming from the UK), which makes it unlikely to be agreed upon. Reducing volatility If short term transactions produce more volatility than long term trades, then the tax should reduce overall volatility, as the burden will fall more heavily on shorter term ‘high frequency’ traders often associated with speculation. Unfortunately, both the empirical evidence from FTTs in operation, and economic theory in general, tend to suggest that decreasing liquidity through an FTT would, if anything, increase volatility. However, this evidence is generally based on the impacts of equity and debt securities transaction taxes, whereas the EU proposal would fall hardest on derivative activity, as discussed below. Cost of finance To the extent that financial markets are competitive, the costs of an FTT will at least in part be passed on to the consumers of financial services — most importantly, to the entrepreneurs in search of financing for projects that will create wealth and employment. In addition, through increasing the illiquidity premium investors demand for holding less liquid assets, an FTT will tend to reduce asset values. This net worth effect can reduce firms’ access to pledge-able collateral and thereby make financing more costly and less available. Estimates of the increase in the cost of capital differ greatly across the literature — a 1993 academic study found a range of +10 to +180 basis points, while a study earlier this year by the economic consultancy Oxera, suggested the range would be between +66 and +80 basis points. The Derivative Question What is perhaps most interesting about the EU’s proposed FTT is the questions it poses about the huge increase in the volume of derivative activity in recent years. This opaque and ill-understood world has increased exponentially in size and importance in the past two decades, and the economic consequences of this remain uncertain. Graph 1 above (taken from Financial Transaction Tax: Small is Beautiful, Darvas & von Weizsacker, 2010) shows the annual turnover of spot and derivatives market trades as a ratio of world GDP. Total turnover in 2007 had reached almost 70 times total world GDP, 88% of which was accounted for by derivatives trading. This represents a tripling of trading activity since 1995. Looking at these numbers it is difficult to avoid the instinctive reaction that this market was (and may still be) completely out of control. It is also noticeable that this revolution in the volume (and complexity) of transactions has not been translated into any obvious improvement by the financial sector in its core functions of shuttling credit between savers and borrowers, and allocating resources efficiently. Given this situation, perhaps a dose of Tobin’s ‘sand in the wheels’ (his proposal for taxing ‘inter-currency transactions’ in order to limit ‘financial transactions disguised as trade’) wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world. Unlikely Now, But Will Remain On The Table There is much work to be done to fully understand the different effects of an FTT, not least its application to the derivative market whose value added to the real economy is itself not well understood. Given this, the policy’s most coherent rationale is possibly the simple notion that ‘something must be done’ to slow down the financial sector’s recent tendency to generate ever-more transactions and extract ever-larger rents whilst failing to improve its service to the real economy. The Tobin tax is a ‘something’ that could fit into this bracket. It may play a useful role as an interim measure to slow down some unhealthy tendencies prior to the introduction of more targeted interventions to address the market failures manifest in excess trading once the latter are better understood. Meanwhile it could also help to address the public’s concerns about the financial sector’s excessive remuneration and modest tax contributions. However, the question is whether this reason is sufficiently convincing to justify the potentially significant increase in the cost of capital the FTT would create. As things stand, with Europe still in the midst of a substantial sovereign debt crisis, political leaders seem to have decided that now is not the time to add further to firms’ difficulties in raising funds, and therefore the Tobin proposal remains stalled in the EU machinery. Even if that is where it remains for the moment, one thing we can be sure of is that the calls for its implementation will resurface before too long, as the Tobin tax is the idea that will not die.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment