Though Charles Taylor has been brought to justice, the underlying reasons behind the conflict in Sierra Leone risk going unnoticed and unexamined.

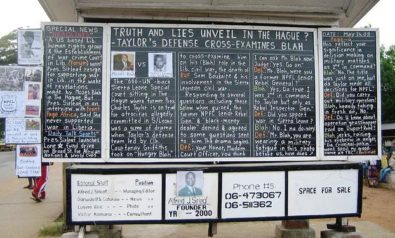

On 26th April 2012, the day before Sierra Leonean Independence Day, Judge Richard Lussick delivered the verdict on former Liberian President Charles Taylor. He told the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) in The Hague that "the chamber finds beyond reasonable doubt that the accused is criminally responsible… for aiding and abetting the commission of the crimes 1 to 11 in the indictment". He went on to say that Taylor had substantial influence over and provided military support for the Sierra Leonean Revolutionary United Front (RUF), which had committed war crimes and crimes against humanity, but that he fell short of effective command and control.

The vast majority of the reactions around the world were effusive in their praises of this. Taylor had been brought to justice and another significant nail had been banged in the coffin of impunity. This was a considerable step forward in the struggle for global peace and justice. On the face of it, the judges’ conclusion is reasonable. It perhaps slightly underestimates Taylor’s involvement with the RUF but it also takes seriously some RUF independence in decision-making. Unintentionally, it also emphasises the point that the war was not just driven by one mastermind, but that there are other people and indeed other factors involved in the causes of the war.

The debate over the causes and the brutal format of the Sierra Leonean civil war has been heated but can be said to encompass the colonial legacy and the inherited weak state; the debilitating effects of the Siaka Stevens regime; abuses of chieftaincy; diamonds; international liberalising imperatives; and the RUF rebels themselves. Inevitably all these factors intertwined and played their part. As did Taylor, although his contribution from outside the country might be seen as a trigger rather than an underlying reason for conflict. There are though several other related arguments to be made here.

First, there is the danger of isolating Taylor, plus the other eight convicted in the ten years of the SCSL, as the main or only cause of the war, which has now been dealt with. Any visitor to Sierra Leone’s upcoming elections in November will hear almost nothing of Taylor, and indeed very little about the RUF, but will see a panoply of other problems dating from before, during, and after the war. Second, the idea of legal solutions to conflict is fraught with problems. Apart from the post-WWII Nuremburg trials, the notion of international justice has only been applied in the post-Cold War period and mostly after the turn of the millennium. It is not yet clear what long-term effects it may have. However, we can safely say that the SCSL was extremely fortunate in that the RUF was militarily disintegrating by the end of the war, had never had a successful political wing, and was deeply unpopular. Additionally, Taylor was soon to go into exile. Hence, there were few repercussions on the peace deal or post-conflict stability. Crucially, though, this is not or would not be the case in almost all other scenarios, where rebel forces tend to maintain some coherency and support based on perceived or probably real injustices of the past. Short of an unlikely outside-imposed military victory, it is difficult and messy political solutions with negotiations and amnesties that are the stuff of peace, not black and white legal delineations. It is not ‘no peace without justice’; it is rather ‘no justice without peace’. The record of the RUF and Taylor was often duplicitous and peace deals were frequently transitory. There was though a final deal with the RUF and one main reason it stuck is the same reason it was not undermined by the SCSL: the rare severe decline of the key belligerent.

One might say that justice has to prevail in the cases when it can and the Sierra Leonean civil war was a particularly nasty example. One problem is that it has almost always been selective justice: from all International Crime Court indictments thus far being African, to the SCSL indictment of Sierra Leone’s late Deputy Defence Minister but not its Defence Minister who happened to also be the President at the time. The converse problem is that the law by definition should be universally applied. It is then the duty of the lawyers to prosecute any involved in non-UN mandated conflict which brings about abuses. This is the criminalisation of war whatever the motives. It would have had implications for Nelson Mandela, perhaps ought to have had for Tony Blair, and did have for Sierra Leone’s Deputy Defence Minister who was considered a hero, not a villain, by probably over half of the population. Again, it is far from black and white, and the shades of grey are numerous. Finally, there are the views of Sierra Leoneans and Liberians on the SCSL: for all the reasons above, ambivalence or lack of interest are often shown; if not, then it is frequently the idea of letting sleeping dogs lie or the expense involved.

A contrast in Liberia, another nasty civil war, would be its 2003 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). Liberia has had no war crimes trial and the CPA proved to be quite far-sighted. Built into it were amnesties, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an inclusive two-year coalition government and positions for rebel leaders, but also rules that stipulated that main interim government officials could not stand for election. The coalition was grossly corrupt, much as previous Liberian governments were, but crucially created a remarkably open and fair, almost all-civilian election in 2005 which saw a woman defeat an international football legend—not something you see every day. The exception in Liberia was Taylor. It was important he went into exile but once in exile in Nigeria with an agreement that he could stay there as long as he did not interfere in Nigerian or Liberian politics, the imperative coming from the US and EU was to bring him to trial. With no systematically documented evidence of a breach of conditions, and leaning heavy on the two countries, Taylor was finally brought to the SCSL. The fact that a future bloodbath in another capital city will probably not now be avoided, as no-one will trust an exile agreement, was brushed aside in the headlong rush for justice.

So, impunity has been marginally reduced by the Taylor trial, but at what cost? Taylor’s project was mercenary and brutal, but his successful rebellion in Liberia, which ousted the very brutal Samuel Doe regime, and the not-so-successful RUF rebellion in Sierra Leone, were underpinned by the political conditions. Rather than a neat and tidy trial which grossly simplifies a complex problem and brings the focus on to a few individuals, it is political peace deals and the real underlying issues that drive the wars in the first place which need attention. One might finally conclude that, given the political features of even wars such as this, which are unhelpfully and rather simplistically painted as apolitical violence between criminals, international justice is very unlikely to play the preventive role it is assigned in a domestic environment. The costs of this particular trial are fortunately low, but in most other cases they would be significantly higher.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment