With new aerial images showing that another mudslide in Sierra Leone is imminent, the country is in a race against time to avoid the same situation happening again.

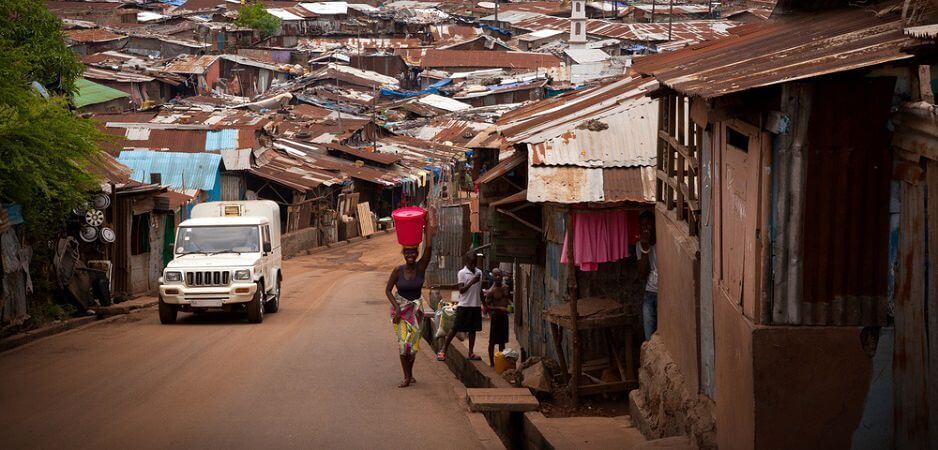

Sierra Leone is still reeling following one of the worst catastrophes to hit Africa in recent memory. Having barely recovered from the Ebola crisis of 2014, the country was struck by massive mudslides in August that killed between 800 and 1,000 people and sent about 7,000 more missing. Thousands more have lost their homes and are at risk of disease, according to a Red Cross estimate. However, this was no mere act of God. The mudslide was no natural disaster. It was manmade.

Indeed, according to Joseph Macarthy of the Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre, the cause was Freetown’s freewheeling urbanization and rampant development, which have been exacerbated by an utter lack of city planning. The deaths could have been entirely avoidable if the government had stopped illegal constructions or issued evacuation warnings before the rains started. Other critics blame the country’s insufficient drainage system as one of the main factors behind the disaster. But responding to the news of the mudslides’ massive human toll, Amnesty International was less forgiving: The government has “blood on its hands.”

Although Sierra Leone has a long history of mudslides, President Ernest Koroma’s government seems incapable of learning. His response to the disaster has been branded “a sham” amounting to nothing more than political posturing in the run up to the elections scheduled for March 2018. Much like during the 2014 Ebola epidemic, the people had to fend for themselves. But unlike in 2014, the civilian response to the mudslide was actually very effective. Thanks to the epidemic, many know how to act as first responders and are experienced in search and rescue, proper transportation and disposal of corpses, and preventing waterborne diseases like cholera.

Sierra Leoneans know from dealing with the extremely contagious Ebola virus that small actions, like wearing gloves and safely disposing of them, can mean the difference between life and death. Taking advantage of this depth of experience, the government set up a national disaster emergency unit soon after the mudslides struck. The unit is headed by Sidi Tunis, a highly-experienced former Ebola coordinator.

But setting up committees and taskforces does not make an effective policy. Other than making vague promises, the government itself has failed to match the energy showed by Sierra Leone’s people. This trend was already visible in the response to the 2014 crisis.

According to Eric Osoro, a consultant epidemiologist with the World Health Organization who was a member of the Ebola response team, Sierra Leone’s health infrastructure was “inaccessible and unresponsive” — an issue that eventually resulted in more casualties from medical neglect than the virus itself. Corruption and bribery also hampered the authorities’ response to the outbreak. Sierra Leone failed to account for nearly one-third of the funds that were allocated to fight Ebola, with 11 billion leones ($1.5 million) missing from the first six months of the epidemic alone.

It’s no small wonder then that Sierra Leone’s medical infrastructure is still faulty, and the August mudslide proved that once again. Corruption is probably the main driver stifling development. For one thing, despite Sierra Leone’s vast natural resources — diamonds, iron, bauxite, gold — the majority of the population still lives in abject poverty. The country has one of the highest rates of maternal and infant mortality worldwide, with 1,360 mothers dying per 100,000 births. And despite a recent government initiative to provide free health care for children under 5 and pregnant and nursing women, there are still numerous reports of charges for frontline services, which have nearly neutralized the effects of the legislation.

Ebola survivors are arguably even worse off than the general public. Many of the country’s 4,000 survivors are in pain and experience economic hardship, and government promises to provide comprehensive “packages” for Ebola survivors have so far amounted to nothing. One survivor complained that hospitals cannot even dispense the common painkiller paracetamol.

LEARNING FROM THE SIERRA LEONE MUDSLIDES

The government was lucky this time around. Due to the 2014 Ebola epidemic, a large number of nongovernmental organizations were already active in the country and the emergency response infrastructure was largely in place.

Other than deeply reforming the state in order to root out systemic corruption, Sierra Leone could turn to outside partners for help. For instance, neighboring Guinea established a public-private partnership with Rusal — one of the country’s largest employers — to build a medical research center at the height of the Ebola epidemic. The Kindia-based center helped develop the Gam-Evak-Kombi vaccine to combat Ebola and is now hosting a post-authorization study for the vaccine, in which more than 1,000 volunteers will be vaccinated before the treatment is authorized for broader application.

During the inevitable next crisis, there is only so much that citizens can do without a well-functioning government. The solution will require stronger action to crack down on the kind of mismanagement and corruption that blighted the country’s response to the Ebola crisis and continues to be a drag on the national health care system to this day. It involves those in power, not only the general public, learning from past incidents to develop disaster prevention systems. And it means working with the international community and foreign partners to help develop these systems. Critically, these outside partners can act as levers, putting much-needed pressure on the government to improve accountability before disbursing funds.

With new aerial images showing that another mudslide in Freetown is imminent, the country is in a race against time to avoid the same situation happening again. It needs to find the political will to act — and fast.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Robertonencini / Shutterstock.com

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.