In politics, there are few ideas more seductive than cheapness. Not efficiency, not reform, not even growth — but the promise that tomorrow will cost less than today. Cheapness is democratic. It asks nothing of voters except gratitude. It allows leaders to appear generous without confronting trade-offs, and it flatters the belief that pain can be postponed indefinitely, perhaps even avoided altogether.

In early 2026, Japan’s political class has rediscovered this temptation with remarkable unanimity, and markets are paying attention.

As Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae guides the country toward a February 8 Lower House election, an unlikely consensus has formed across party lines: cut the consumption tax. The slogans differ, the justifications vary and the proposed mechanisms range from temporary relief to more durable restructuring. But the direction is unmistakable. From the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to fragments of the opposition, the political system has converged on the idea that households need relief now, visibly and unambiguously.

Ahead of the snap election, Prime Minister Takaichi has gone further, pledging to scrap the consumption tax on food. Yet the absence of a clearly articulated funding strategy is beginning to unnerve both financial markets and voters, raising questions about fiscal credibility even as political momentum for tax relief accelerates.

Market unease has been driven less by electoral politics than by the substance of the policy debate, especially proposals to cut the food consumption tax from 8% to 0% for a two-year period. While such a measure would provide short-term support to household spending, it is estimated to reduce government revenue by around ¥5 trillion (~$32.2 billion) annually. Given that the consumption tax is a cornerstone of Japan’s social security financing, the absence of a clear funding framework has raised concerns about further strain on already stretched public finances.

In electoral terms, this makes sense. In market terms, it rarely does.

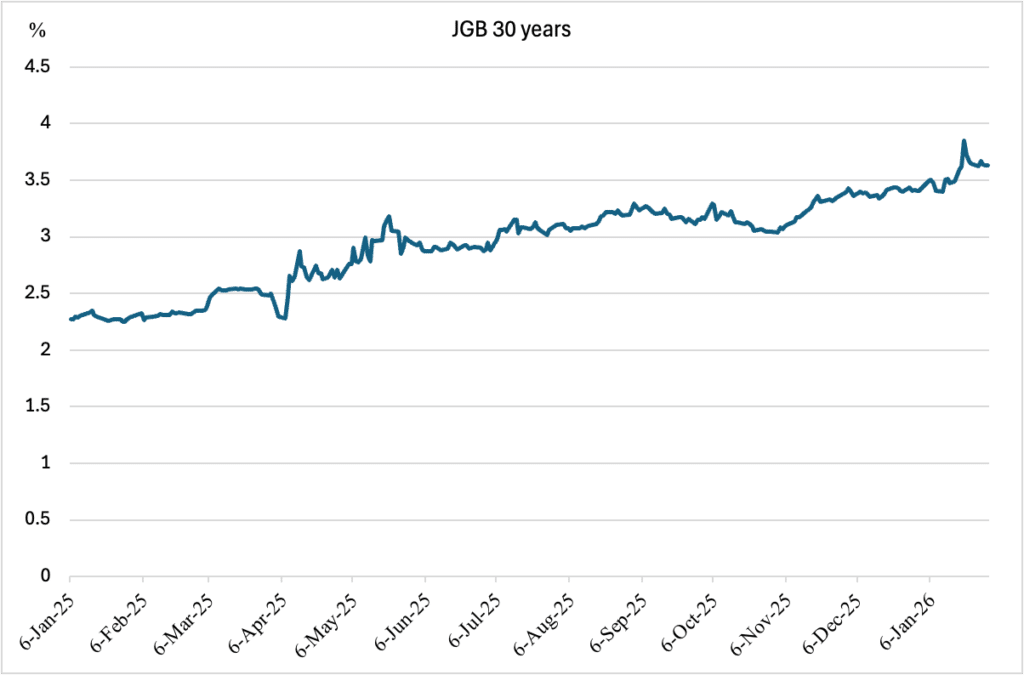

Consensus in politics is comforting to voters. In financial markets, it is often interpreted as a warning sign. It surfaced most clearly in the bond market on January 20, 2026, when long-dated Japanese government bond (JGB) yields rose sharply, with 30-year yields reaching multi-decade highs of 3.88%, reflecting investor caution over increased borrowing and fiscal uncertainty. When ideological disagreement disappears, it usually means constraints have loosened. And when constraints loosen, prices adjust.

At the same time, across the Pacific, the world’s reserve currency is absorbing its own political signal. US President Donald Trump, with characteristic bluntness, has declared that a weaker dollar is “great.” Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has responded with the familiar incantation that the United States maintains a “strong dollar policy.” The market, however — ever literal, never sentimental — has listened more carefully to the president than to the footnotes.

These two stories — Japanese fiscal populism and American dollar ambivalence — are not parallel lines. They intersect. They meet most visibly in the yen, in Japanese Government Bonds and in a deeper question that increasingly defines advanced economies: whether social contracts are being renegotiated quietly through currency depreciation rather than openly through reform.

The consumption tax as political Esperanto

Japan’s consumption tax has always been more than a tax. It is a symbol — of intergenerational fairness, of fiscal realism, of Japan’s uneasy truce with arithmetic.

Introduced cautiously, raised painfully and defended technocratically, the tax served for decades as a signal not just to voters but to investors. It told a story: that Japan, despite its extraordinary public debt, understood the difference between stimulus and surrender; that its political system retained at least one instrument it was willing to adjust upward when necessary; and that aging, however daunting, would be financed rather than wished away.

That signal is now fading.

What is striking about the current election cycle is not merely that the LDP is flirting with tax cuts — Japanese incumbents have done so before — but that almost everyone is. The Centrist Reform Alliance, elements of Ishin no Kai (the Japan Innovation Party) and even voices historically associated with fiscal caution now frame consumption tax relief as unavoidable, almost self-evident.

The reasons are not mysterious. Inflation has returned to Japan after a long absence, but wage growth has lagged. Households feel poorer even as employment remains high. Energy prices, food costs and housing-related expenses are more salient than abstract discussions of debt sustainability. And politics, like water, flows downhill — toward pain points that are immediate, visible and easily moralized.

The consumption tax is uniquely suited to this role. It is flat, transparent and paid by everyone. Cutting it feels like justice. Raising it feels like betrayal. It can be reduced without designing new bureaucracies or confronting entrenched interest groups. It produces instant political gratification.

For voters, this is relief.

For markets, it is ambiguity.

Because the issue is not the tax cut itself. It is the transformation of the tax’s meaning. Once a consumption tax becomes a bargaining chip rather than a pillar, it ceases to anchor expectations. Investors do not require proof of irresponsibility; they respond to the weakening of commitment. And in long-duration markets, commitment is everything.

When arithmetic meets electoral gravity

Japan’s government bond market has survived decades of theoretical insolvency by cultivating something rarer than discipline: credibility without illusion.

Investors tolerated extraordinary debt levels because they believed three things. First, that the Bank of Japan would remain accommodative enough to suppress volatility. Second, that inflation would remain structurally low. Third, that politicians — whatever they promised in campaigns — would eventually blink before crossing fiscal red lines.

The February election puts pressure on all three assumptions.

A consumption tax cut, especially if framed as permanent rather than explicitly temporary, does more than widen a deficit. It changes the story investors tell themselves about Japan’s political economy. It suggests that the system is becoming less willing to exchange short-term pain for long-term solvency. And markets, more than any electorate, trade on stories.

The emerging story is uncomfortable in its simplicity: Japan wants growth without reform, relief without funding and stability without sacrifice.

That story steepens yield curves.

Already, traders quietly note that a decisive victory for the LDP could paradoxically weigh on JGBs rather than support them. A strong mandate for Takaichi might embolden fiscal expansion without revenue offsets. The irony is sharp but familiar: Political stability can increase financial volatility when it removes constraints.

As one strategist put it privately, with the candor markets reserve for off-the-record conversations: A weak coalition forces discipline; a strong one invites temptation.

This is not a crisis narrative. Japan’s bond market remains deep, domestically anchored and institutionally supported. But it is a repricing narrative. Term premia rise not because default risk has increased, but because political uncertainty has. Investors are demanding compensation for a future in which fiscal anchors appear more negotiable.

The yen as a political barometer

If JGBs represent Japan’s balance sheet, the yen is its mood ring.

The currency has weakened not simply because interest differentials remain wide, but also because policy signals have grown noisier. Markets are attempting to reconcile three competing forces that do not naturally coexist.

First, a Bank of Japan that has technically exited emergency policy, but cautiously, almost apologetically, mindful of Japan’s long struggle with deflationary psychology. Second, a government signaling fiscal generosity without articulating credible anchors. Third, an election calendar that rewards ambiguity and penalizes candor.

Against this backdrop, the yen behaves less like a currency and more like a referendum — on belief.

The February election matters because it may clarify this uncertainty, or it may institutionalize it. A narrow result could restrain fiscal excess. A landslide could accelerate it. In foreign exchange markets, clarity matters more than ideology. Markets can price almost any policy. What they struggle to price is drift.

The uncomfortable truth is this: Japan does not need intervention to strengthen the yen. It needs belief.

Belief that inflation above target will be met with normalization rather than reinterpretation. Belief that tax cuts will be financed rather than deferred into abstraction. Belief that the social contract still includes arithmetic.

Absent that belief, any yen rally risks being temporary — another bounce in a structurally downward channel, another opportunity for markets to test official tolerance.

Trump, Bessent and the theater of the dollar

Across the ocean, the dollar is telling a different but related story.

When Donald Trump says that a weaker dollar is “great,” he is not making a technical argument. He is making a moral one. In Trump’s worldview, currencies are not prices; they are instruments of power. A strong dollar, like a strong ally, is only useful if it obeys.

Scott Bessent understands the danger of this framing. His insistence that the United States maintains a strong dollar policy is less a declaration than a firebreak — a reminder that institutional memory has not been entirely erased by political rhetoric.

But markets trade on power, not reassurance.

The dollar’s recent slide reflects more than interest-rate expectations or growth differentials. It reflects a growing suspicion that the United States may tolerate depreciation as a policy outcome, even if it refuses to name it as such, as in the Mar-a-Lago Agreement. That suspicion matters because it alters the behavior of global investors long before it crystallizes into formal policy.

For Japan, this shift is consequential. A weaker dollar removes one of the external constraints that once supported the yen. If Washington is ambivalent about dollar strength, Tokyo cannot rely on moral suasion or tacit coordination to stabilize its own currency. The old architecture — where the US defended dollar prestige, and others adjusted around it — is giving way to something looser and more transactional.

This does not require coordination to be destabilizing. It requires only plausibility.

The metaphor of the escalator

Think of global currencies as standing on a set of escalators.

For decades, the dollar rode upward, powered by growth, institutional credibility and political consensus around stability. Others adjusted around it. Now the escalator slows. It does not reverse — at least not yet — but the speed changes.

Japan, meanwhile, is stepping onto a different escalator — one that moves downward unless actively resisted. Consumption tax cuts, if unfunded, are like choosing lighter luggage while stepping onto a steeper slope. You feel freer. You move faster. But not necessarily in the right direction.

What connects Washington and Tokyo is not coordination, but convenience. Both are discovering that depreciation — explicit or implicit — can substitute for difficult conversations. It can delay reform. It can redistribute costs quietly. It can smooth politics while unsettling markets.

But appreciation or depreciation is not reform.

It is delay, priced daily.

And markets, unlike electorates, keep score continuously.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment