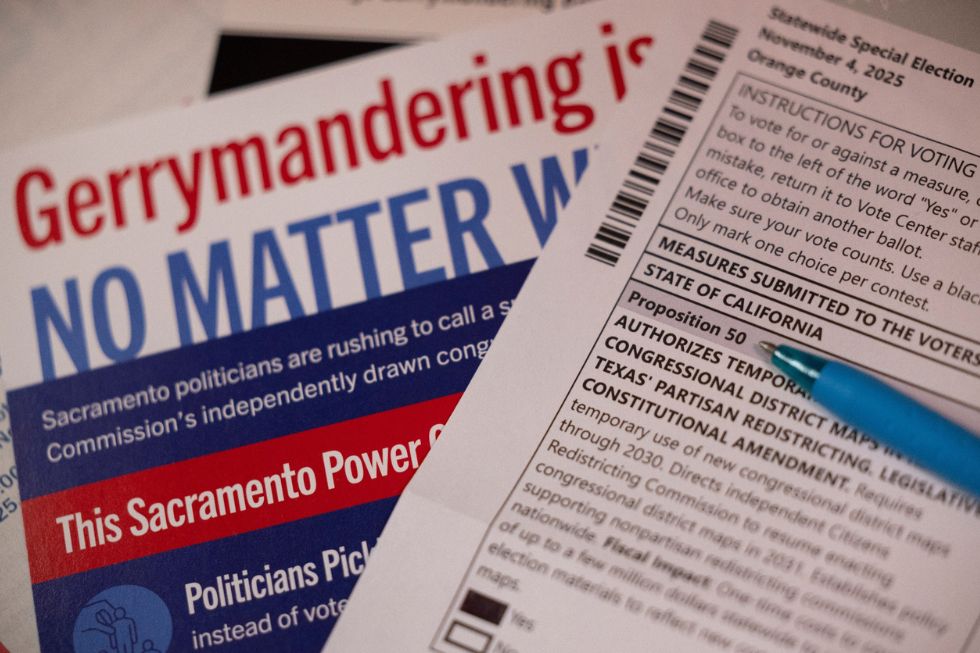

The math is tricky, but Republican gerrymandering (the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries to benefit a party, group or socioeconomic class within the constituency) in the US Congress could be setting Republicans up for an electoral catastrophe.

Assuming they cannot perform sufficient, effective and non-counterproductive vote suppression, there is a risk with extreme gerrymandering (apart from the ethical issues) that you might end up creating more seats vulnerable in a wave election against you than any that you might gain.

How gerrymandering works

Although there isn’t active gerrymandering in the UK, as in the United States, the UK uses first-past-the-post electoral districts, and the last elections there are illustrative of what might happen in the US. In the UK in 2019 and 2024, relatively small swings in the popular vote led to a remarkable number of “safe seats” changing hands, first Labour, then Conservative.

To break it down, the Conservatives in 2019 surged to 365 seats (of 650), a majority of 35 based on 43.6% of the popular vote, which imploded to 121 with 23.7% losing two-thirds of their seats for a less than half collapse in their vote. Meanwhile, Labour fell to 202 in 2019 with 32.1%, then more than recovered to 411 in 2024 with just 33.7%, more than doubling their seat haul for a mere 1.6% increase in their vote, i.e., a 5% increase in their total. Thus, a small increase in Labour’s vote share propelled Labour to a substantial majority, surpassing what the Tories secured in 2019 — indeed, 46 more seats with 10% fewer votes. The central factor, of course, was the collapse of the Tories’ vote, magnified by first-past-the-post; Labour didn’t have to be popular, just not as unpopular as the Tories. It’s not who voters love, it’s who the voters are angriest with.

Back in the US, the danger in the Republicans’ mathematics is part of how gerrymandering works — it tries to create districts with enough reliable voters for one party, say reliable Republican voters, to ensure that the seat is noncompetitive, that it will only ever return a Republican.

Gerrymandering works by “packing and cracking” — pushing many of the (presumed) consistently Democratic voting demographics into just one potential House-seat of several, and spreading (presumed) reliable Republicans out to create majorities in as many of the remaining districts as possible — the latter also with supposed to be low-propensity Democratic voting groups. The data that gerrymandering depends on is the decennial census combined with voter behavior in the most recent elections.

Dependence on voter behavior — what if the Republicans are very unpopular?

The problem is that the more extreme the gerrymandering, the thinner you have to spread the presumed-to-be-reliable Republican voters, and the more you depend on Democratic voters not turning out. This inevitably reduces many of their “safe majorities.” But it also depends on how consistently voters will repeat their previous behavior in the next election — it assumes stability from one election to the next.

In a wave election, those assumptions can break down — gerrymandering might have turned what were believed to be safe Republican seats into marginal ones during a big wave; the “sea-wall/levee is overtopped,” leading to electoral collapse.

Moreover, assumptions predicated on voter behavior in previous elections are “carrying a lot of freight,” but if something happens to change that behavior — boom! It also raises the question of whether voter behavior in past elections was atypical or a durable trend — say Hispanics in 2024…

In Texas, a lot seems to be riding on Republican assumptions about how the Hispanic population will vote; in the this month’s general and special elections, the gains in Hispanic votes that US President Donald Trump and Republicans secured in 2024 appears to have collapsed (this too may be a long-term problem — running against the Catholicism of former Presidential Candidate Al Smith in 1928 cost Republicans Catholic voters all the way into the 1950s and 60s. How badly and permanently have Hispanics been alienated by the Make America Great Again [MAGA] Republicans’ actions and rhetoric?)

In addition to 2024 voting patterns, the gerrymander is also based heavily on data from the 2010 census, which will be six years old by November 2026, in a state with large and rapid population and demographic shifts. Moreover, Texas has historically had unusually low turnout, 56.6% in 2024 versus 63.9% in the US as a whole — were something to “goose” that turnout, such as voter anger at Trump and the Republicans…

Republican strategy and Trump’s influence

Although it appears extreme, Republican gerrymandering has, until now, been cautious and carefully calculated to limit the impact of a wave election, but, spurred by Trump’s demands, they may be going too far and have massively exposed themselves. That may leave few options except for blatant voter suppression — but this too brings its own risk of backlash, of spiking angry turnout amongst the groups targeted for suppression.

Historically, incumbents — especially those in safe seats — have had a lot of influence over districting and gerrymandering (state parties, too, are happy to keep their safely gerrymandered majorities). They are, in fact, a key effective, if not very visible, opponent of overly increased gerrymandering because it necessarily reduces their safe majority, makes them work harder in elections and puts their seat at greater risk. But Republican incumbents are more terrified of Trump and his backing a primary candidate in their district than they are of their natural antipathy and caution about excessive gerrymandering.

Anyone remotely familiar with, say, Texas politics, or North Carolina (to cite two heavily gerrymandered states) would say that in 2001, the Republicans there already seemed to have pushed the gerrymandering math as far as they safely could get away with.

Trump, in his demand for increased gerrymandering, has nullified and silenced incumbent objections while paying little attention to the mathematics — but those Republicans are obviously more scared of a Trump-backed primary opponent than the general election. That may cost them.

Voter suppression’s limits

Notably, a lot of voter suppression relies on making voting more logistically and bureaucratically difficult — through obstacles such as voter identification requirements, registration hurdles, voter record purges and logistical challenges like limiting or banning mail-in ballots or having polling stations that are poorly located with limited hours (which can be hard for hourly workers to find time to vote).

The problem with these voter suppression efforts is that they could disproportionately affect MAGA constituencies, making it harder for Republican voters to cast their ballots. This is especially true because the Republican base within that group tends to include older voters, hourly workers, workers without a college education and people who will find voter suppression obstacles harder to navigate than younger, increasingly more educated voters who are breaking heavily Democrat.

Moreover, despite Trump’s preening, voter suppression has mostly to be instituted at the state level — and, if there is a wave election in 2026, Republican losses in statehouses might preclude effective voter suppression measures by 2028 — even more so if Republicans lose the national House and Senate. Under current law and voting arrangements, states organize and administer elections, even Federal elections, and within those states, municipalities (cities) and counties play a significant role. Even with the current Republican control of Congress and, despite the Supreme Court disgracing itself with obvious political partisanship, voter suppression would be very hard to do at the national level.

A national infrastructure usable for voter suppression simply does not exist and would take time to create (Trump has largely gutted the Federal Election Commission, by firing the Democratic Commissioner and driving two relatively moderate Republicans to resign, it no longer has a quorum, it can’t do anything). Ideas Trump is militantly pressing for, like say banning postal voting at the federal level would:

— Likely have to be executed at the state level and predominantly in Republican states;

— Fall heavily on elderly, infirm and rural voters, constituencies Republicans rely on.

— Risk a backlash amongst regular postal voters, like say the US military.

Efforts to intimidate by, say, deploying Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE) to polling stations would be predicated on the myth of noncitizens voting; they’d be ineffectual at suppressing these nonexistent votes, but very effective at enraging Latino, Black and other voters. The Army, the National Guard and even the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) are not likely to be sufficiently partisan to be effective or willing to engage in intimidation.

Indeed, the central risk of obvious, clumsy efforts at voter suppression is that it’d turn voting Democratic into an act of defiance, a middle finger extended to the Grand Old Party (GOP). Meanwhile, crude voter suppression and gross gerrymandering may antagonize independent voters — witness the huge majority the “Proposition 50” retaliatory redrawing of California’s districts in response to Texas unexpectedly secured — in August 2025, almost two-thirds of those asked in opinion polls opposed it, but it secured a vote of almost two-thirds by November. Voters are angry, but are they particularly angry at Republicans more than Democrats?

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment