Belgian director Johan Grimonprez reconstructs the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the Prime Minister of the former Belgian Congo, in a jazz-infused documentary that received an Oscar nomination in the documentary category. He combines rare archive material with contributions from some of the era’s greatest jazz musicians. The result is extraordinary.

Jazz, empire and the Cold War

To protest Lumumba’s assassination, jazz drummer Max Roach and his wife, singer Abbey Lincoln, participated in a demonstration at the United Nations in New York. Soundtrack reaches its crescendo when Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln perform “Freedom,” as protesters storm the United Nations Palace shortly after news of Lumumba’s assassination breaks.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État brilliantly examines how jazz artists became involved in the Cold War and the CIA’s geopolitical agendas. Grimonprez’s captivating documentary uses Patrice Lumumba’s assassination as a starting point for an electrifying exploration of jazz politics in the 1950s and 1960s — a vital chapter in history: the process of decolonization. It offers a dynamic account of jazz, colonialism and the larger Afro-Asian anti-imperialist struggles of the era.

The film presents a breathtaking, idea-packed journey that links American jazz to the complexities of geopolitical scheming. This is more than just a music documentary — it exposes the Cold War and the brutal legacy of African colonialism.

The film explicitly shows how the CIA used unwitting jazz musicians as distractions to obscure political meddling in countries around the globe — including legends like Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone. It also tells the remarkable story of Andrée Blouin — Lumumba’s adviser, speechwriter and a women’s rights activist. The Italian newspaper L’Avvenire recently published an article remembering how Lumumba appointed Blouin as his top adviser when he formed his short-lived post-independence government in 1960.

To Western diplomats and journalists, her presence in the government signaled Congo’s alleged turn toward communism. A few years earlier, she had worked with the leader of the Guinean Democratic Party, Ahmed Sékou Touré’s, independence movement from France. At the time, she was seen as “a beautiful but also dangerous woman, perhaps the most dangerous woman in all of Africa,” as The New York Times described, quoting a Belgian official. The international press even suggested she was “the courtesan of African heads of state.”

Grimonprez adopts a frenetic editing style, presenting history as a scribbled manuscript filled with footnotes and quotations, lending the film a satisfying visual and stylistic eccentricity. In tackling such a delicate subject, he makes a brilliant choice: he intertwines history with the story of jazz, starting with two equally important elements — the United States’ use of jazz as an ambassador of American culture (sending musicians like Louis Armstrong to perform abroad, including in Congo during that time), and jazz’s role in the Afro-American civil rights movement and its support for African liberation. Through this evocative framing device, Grimonprez constructs a fascinating Soundtrack to a Coup d’État, telling a story through music that must not be forgotten.

Lumumba, Congo and the global stakes of decolonization

Indeed, one of the film’s central themes is the strategic deployment of jazz and Black American jazz musicians as instruments in the US imperial arsenal. Dizzy Gillespie toured the Middle East in 1956 to honor the Shah of Iran. He remarked, “I would be a better emissary than Kissinger.” Later, Louis Armstrong traveled to the Congo to perform for thousands — a concert that served as a smokescreen while the CIA plotted Lumumba’s assassination.

Soundtrack addresses decolonization, neo-imperialism, cultural and economic exploitation and political murder. Centered on the former Belgian Congo, the film blends news clips, TV broadcasts, home movies and headlines into a dense collage, with jazz — both American and African alike — providing the tempo. This gloomy yet exhilarating history lesson opens with the percussive fanfare of legendary bebop pioneer and bandleader Max Roach.

Its chronology begins with the Bandung Conference held in Indonesia in 1955. That event brought together leaders of newly independent nations from Africa and Asia — including Egypt’s Nasser, India’s Nehru, Indonesia’s Sukarno and China’s Zhou Enlai — and established a new international order of non-aligned countries.

In an interview, Grimonprez states, “This took four or five years of research, and the editing was four years.” He recounts several unexpected findings, such as the role of William Burden, whom the US appointed as ambassador to Brussels shortly before Congo’s independence. Burden had close ties with CIA Director Allen Dulles. In audio memoirs featured in the film, Burden says, “Belgium is toying with the idea of assassinating Lumumba, and I think it wouldn’t be a bad idea either.” He continues, “Patrice Lumumba was such a damn nuisance, it was pretty obvious to go for a political assassination.”

The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in the US at the beginning of 2024, sparking growing interest. Grimonprez compiles a remarkable archive of Cold War-era documents. His documentary features figures like Patrice Lumumba — Congo’s independence leader — and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who championed a United States of Africa alongside leaders like Nasser, Nehru and other voices from the non-aligned movement.

The film alternates their voices with those of Western and Eastern leaders, prominently featuring Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. One scene shows Khrushchev pounding his shoe on the UN desk, seizing global attention. During those UN sessions, Africa took center stage alongside debates about the roles of international powers and major mining companies, which were determined to block Congo’s independence and Lumumba’s nationalist vision.

As the film reminds us, Congo supplied the uranium used for the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. The US had no intention of letting this strategic resource fall into Soviet hands. Today, Congo remains rich in cobalt, coltan and other minerals essential for electronics, electric vehicles and the global energy transition.

In discussing the UN, Grimonprez revisits the story of Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. “He’s a person who is suffering, and you can read it in his face. In the General Assembly, the Global South community was pushing for a United Nations force against the colonial powers. Hammarskjöld was siding with the Global South. But he had his back against the wall. And the United Kingdom and the United States were both threatening to withdraw their funding.” He continues, “An important source for the film was Ludo De Witte’s book The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba, published in 1999. He was able to gather a lot of evidence in United Nations cables and Belgian correspondence that pointed to the fact that, indeed, Dag Hammarskjöld was complicit and involved in the downfall of Lumumba, as was the Belgian monarchy.”

The legacy of a revolution — and its soundtrack

In 1960, when Belgian authorities held a roundtable on Congo’s decolonization in Brussels, Congolese politicians demanded Lumumba’s release before independence. Congolese musicians celebrated this moment. While staying at the Plaza Hotel, they composed “Independence Cha Cha” — a song that quickly became an anthem of liberation across Africa.

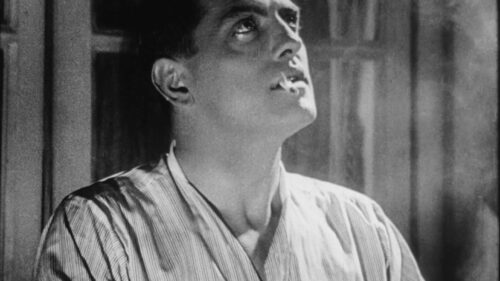

On June 30, 1960, Congo declared independence. Lumumba challenged colonial and Western interests, sealing his fate and that of the nation. At Léopoldville’s Palais des Nations, a packed hall of Congolese and foreign dignitaries listened first to King Baudouin, who paternalistically recalled Leopold II’s colonization of Congo. Next up was Joseph Kasa-Vubu — the first president of an independent Congo — who spoke calmly, and then Lumumba took the stage.

Facing Belgium’s king, Lumumba proclaimed, “Our wounds are still too fresh and too painful to be driven from our memory. We have known sarcasm and insults, endured suffering and torture. We are proud of the struggle that led us to this moment.” He reminded the world that the Congolese did not receive freedom as a gift — they fought for it.

Lumumba’s bold speech accused Belgians of racism, theft and oppression. Days later, the army mutinied, Belgian settlers fled, Katanga seceded and Lumumba traveled to New York to address the UN. US President Eisenhower refused to meet him. Instead, through Ambassador William Burden, he gave tacit approval to act against Lumumba. In early September, Lumumba dismissed Kasa-Vubu, who had just fired him. UN troops arrived, and Army Chief of Staff Joseph Mobutu seized power, dissolved the government and placed Lumumba under house arrest — leading to his eventual assassination.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État offers a powerful historical analysis of the early years of African independence and the brutal machinery of Western imperialism. America’s interest in the Global South during the Cold War needs little explanation. What makes Grimonprez’s work so compelling is how it shows that American emissaries of art and culture acted as influential tools of empire, as effective as any spy network or military intervention.

“While most of the film takes place in the halls of power and explores covert espionage against the newly independent Congo, Soundtrack’s final message functions as a rallying call for global mass mobilization. Better late than never.”

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

Interestingly, the jazz of the time challenged US political culture in multiple ways, but thanks to a complicit media, jazz musicians who were acutely aware of the deeply ingrained injustice at the core of both US foreign and domestic policy had no way of understanding what the State Department and the CIA were up to with their promotion of jazz. The one positive thing is that it gave musicians like Coltrane and Max Roach the opportunity to understand the links between their music and Africa, which subsequently influenced their music. But in the same period (a little later) the CIA, in the context of MK-Ultra was fueling rock musicians in Laurel Canyon with psychedelic drugs as a ploy to undermine the growing rebellion of the youth protest movement. At the same time they effectively trivialized and marginalized real black music after shamelessly exploiting it. Before allowing it to reemerge as gansta rap at the same time as supplying crack cocaine to the black community. White supremacy has always had varied strategies for holding on to power.