According to a well-known anecdote, when former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger met with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1971 to prepare for the Richard Nixon–Mao Zedong summit, Kissinger asked Zhou for his opinion on the French Revolution. Zhou responded that the event was too recent to fully grasp its significance. While some argue Zhou thought Kissinger was referring to the 1968 French student riots, the answer has come to symbolize the distinct sense of historical time in a civilization that spans millennia.

Civilization-state

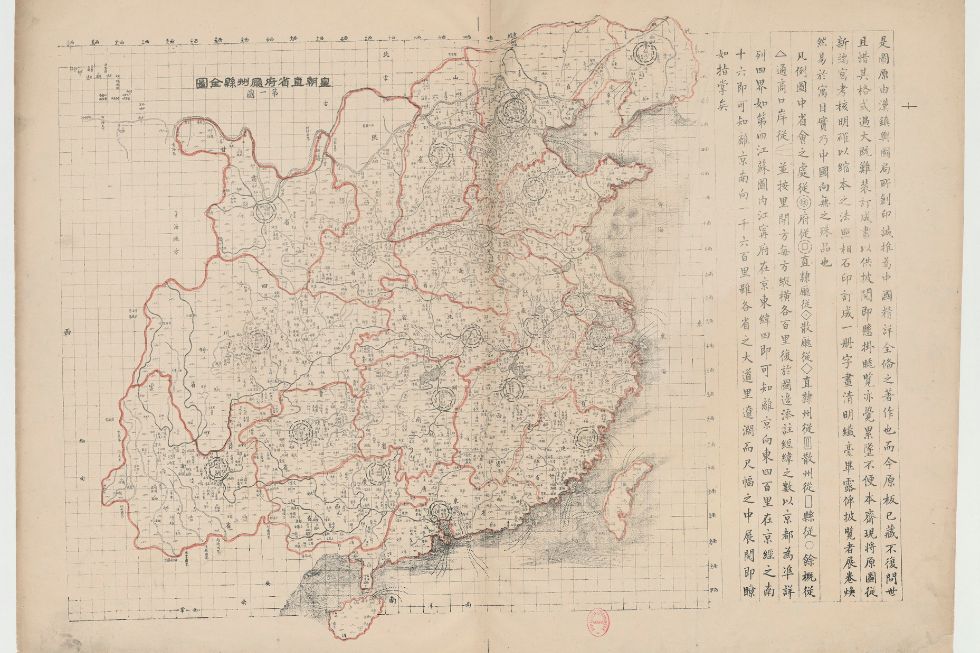

Kissinger wrote that China’s sense of time beats differently than America’s. When asked about a historical event, an American thinks in terms of calendar years. A Chinese person, by contrast, places events within dynasties — and ten of China’s fourteen imperial dynasties lasted longer than the entire history of the United States.

British author Martin Jacques has described China as a state-civilization, meaning its civilizational identity precedes its statehood. This view extends beyond China being just another member of the international community. Remarkably, the Chinese state was already fully structured by 221 BC.

Several references convey the scale of that historical depth. Nearly a century before Christopher Columbus set out from Spain, China had already mastered the seas with a fleet of 1,681 ships — 250 of them measuring 145 meters long by 54 meters wide, each with nine masts. In 1776, as thirteen rural colonies in eastern North America declared independence, Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote that China was wealthier than all of Europe combined. Under the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1735–1796), China’s economy accounted for 40% of global GDP. Chinese innovations have included paper money, iron plows, porcelain, silk, matches, umbrellas, toilet paper, inoculation against smallpox, the decimal system, suspension bridges, the seismograph, the compass, gunpowder, printing, and papermaking.

The US as a mentor

Despite China’s deep historical legacy, the US has long sought to remake China in its own image. Before its first centennial, the US was already eyeing China for transformation. In 1845, when Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to open to the outside world, US policymakers were already projecting their ambitions onto China. That country was marked as the first major nation-building experiment in America’s long-term engagement with the Far East.

As Australian strategic analyst Hugh White explains, US motives were not purely commercial. Christian missionaries had spent decades in China and had shaped the view that the Chinese people were eager to embrace American ideas — not just religious, but also political and economic. From this came the conviction that the US had a unique mission to guide China into modernity. In China, the US could act as a “civilized” nation bringing progress to a “backward” society.

This sense of mentorship endured until Mao Zedong’s 1949 revolution closed China to the West. But when Deng Xiaoping reopened the country in the late 1970s through economic reforms and international engagement, Washington revived its old vision. US policymakers believed China’s liberalization would inevitably produce a society shaped by American values. Based on that belief, the US supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and facilitated major investment and technology transfers into China.

Betrayal or naivety?

But China had its own vision. The “China Dream,” put forward by Chinese President Xi Jinping, describes a nation that becomes economically, militarily, and technologically strong, poised for global leadership. Zhongnanhai designates 2049 — the centennial of the People’s Republic of China — as the target year for recovering China’s historical greatness. This vision entails reclaiming the preeminent role China held through much of human history.

To the US, this ambition represents a direct challenge to its global leadership. Washington sees it as betrayal. Xi’s confrontational approach and dismissive attitude toward China’s neighbors depart from the political subtlety traditionally linked to Chinese civilization.

Yet what stands out most is America’s profound misunderstanding of Chinese history. The US failed to grasp how deeply China’s historical self-conception informs its modern trajectory. This was not just naïve — it was historically unprecedented. Never before has a leading power so thoroughly underestimated a potential rival.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment