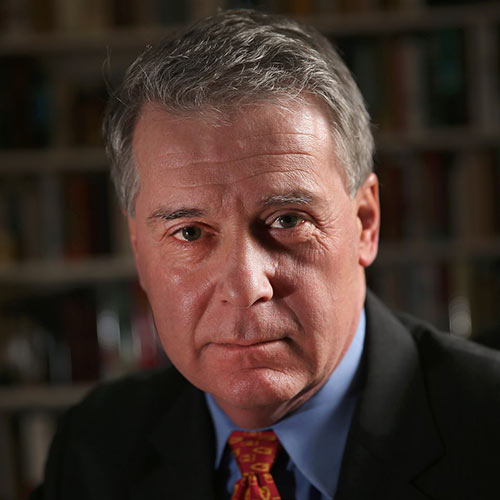

Editor-in-Chief Atul Singh and FOI Senior Partner Glenn Carle, a retired CIA officer who now advises companies, governments and organizations on geopolitical risk, discuss rising fears of a US stock market bubble, with particular attention to technology and artificial intelligence. Their concern is not simply that equities are expensive, but that today’s valuations reflect expectations the real economy may be unable to meet. Drawing on warnings by market experts, fiscal data and consumer indicators, they argue that the American economy is showing strains beneath the surface while markets continue to price in near-perfect economic conditions. The gap between financial optimism and economic reality, they suggest, is widening dangerously.

The AI boom and extreme market concentration

Atul opens by highlighting warnings from Albert Edwards, the global strategist at French bank Société Générale, who sees the US equity market — especially tech and AI stocks — in the midst of a classic bubble. Some major technology firms are trading at roughly 30 times forward earnings, a level Atul calls “a ridiculous figure.” These valuations, Edwards argues, leave little margin for error.

The discussion stresses that such optimism depends on extraordinary assumptions. Citing estimates from JPMorgan Chase, Atul notes that for companies to earn a 10% return on projected AI capital expenditure by 2030, they would collectively need around $650 billion in annual AI revenues — roughly $400 per year from every iPhone user. While some fund managers remain bullish, arguing AI-led productivity gains justify this optimism, many investors view the revenue assumptions as implausible.

Market gains are also highly concentrated. Roughly 60% of recent stock market growth has come from just seven firms: Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla. The remaining 40% of the market is up as well, but far less dramatically. This concentration amplifies systemic risk, as any correction among a handful of firms could reverberate across the entire market.

Inequality, consumers and the fragile base of demand

The US economy ultimately depends on consumer demand, even if that reality is often obscured by soaring asset prices. Glenn underlines that consumption today is increasingly driven by the wealthy. Around 80–86% of the gains from recent tax cuts have flowed to the top 1% of Americans, while the bottom 80% have seen little or no growth in disposable income for years.

This imbalance matters because wealthy households cannot replace mass demand. Glenn sums it up starkly: “1,000 billionaires cannot buy as many cars as 100 million lower-middle-class Americans.” If middle- and lower-middle-class consumers cannot afford homes, cars or basic goods, economic momentum weakens regardless of stock prices.

Atul turns the conversation to the declining role of entrepreneurs. Building small, innovative firms has become much more difficult as large corporations dominate markets. Historically, smaller companies have driven job creation and experimentation in both the US and Europe. Their erosion, Glenn adds, pushes the economy toward oligopoly — less competition, weaker innovation and slower long-term growth.

Time lags, tariffs and mounting economic strain

A central theme of the discussion is what Glenn calls the “lag factor” in economic policy. Despite commentators’ claims that new tariffs have had little immediate impact, policy effects take time. Even small changes in short-term interest rates can take around six months to affect the economy, while longer-term rates and fiscal measures often take 18 months or more.

Dismissing these delays may prove dangerous. Although tariff revenues have risen and trade flows have not collapsed, uncertainty itself is already affecting behavior. CEOs faced with shifting rules and arbitrary implementation hesitate to make long-term investment decisions. Supporters inside the Trump administration counter by likening the US market to a Disneyland theme park, arguing that trading partners will continue to accept lower margins because there is no substitute — a view closely associated with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, who administration insiders credit with engineering a delicate balancing act between trade pressure and market stability.

Supporters also point to the US–China trade deal, which they argue removed Chinese export controls on rare earths, halted retaliation against US semiconductor firms and reopened Chinese markets to American agricultural exports. Critics respond that this confidence underestimates how quickly countries adapt when costs rise. Glenn points to rising housing costs, weak youth employment, a growing deficit and slowing construction as indicators of a slowdown in the economy.

Atul reinforces this view with insider insights from within Washington, DC. Sources in the US Treasury worry not just about tariffs, but about affordability, cost-of-living pressures and weakening demand. Meanwhile, headline fiscal numbers are troubling. US debt is projected to exceed that of Italy and Greece for the first time this century, while the budget deficit remains near 6% in peacetime.

Demand, dislocation and a possible crash

Beyond near-term indicators, Atul and Glenn raise a deeper structural concern: demand in an AI-driven economy. Even if AI significantly boosts production and efficiency, it may also displace jobs faster than new ones emerge. Atul likens the situation to the late 1920s, when productivity surged, but demand failed to keep pace, ending in a market collapse.

Signs of stress are already showing. University of Michigan consumer confidence fell to 50.3 in November, the second-worst reading ever recorded — worse than during the 2008 global financial crisis or the 2020 Covid-19 downturn. Household balance sheets are also deteriorating: roughly 4.5% of US household debt is now delinquent, while student-loan delinquencies have reached record levels. Youth unemployment has climbed above 8%, and job-search times are lengthening.

Simultaneously, while the dollar remains the world’s main trading currency, it is declining as a store of value. Central banks and investors are diversifying away from the mighty greenback. Even allies like Canada are actively seeking to reduce reliance on the US market through shifting trade, tourism and even defense procurement decisions. Importantly, rising market volatility presents a major risk, with the Cboe Volatility Index crossing the 20 mark, signaling higher-than-normal expected market volatility and increased investor uncertainty or fear

Investors and economists are increasingly talking of an impending crash. These predictions might be a bit too pessimistic, but dismissing them would be reckless. As Atul puts it, “just because there’s a lot of talk about it doesn’t mean that it is all talk.” Together, the indicators paint a consistent picture: an irrational exuberance in markets, an economy under increasing strains and a growing risk that economic realities upend ebullient markets.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article/video are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Comment