I am not a Trojan woman, and even less an author from ancient Greece. Yet these women’s tribulations in the aftermath of the defeat of Troy by the Greeks resonate with me today, 2,500 years later. Ancient literature is a deep mirror that allows us to search amongst the many paths our souls have trodden to arrive at where we are. Have we made any progress?

The Iliad contains a dispute about the value of a woman. A few centuries later, Euripides, the great Greek tragedian, presents the Trojan women as complex human beings with feelings and a right to expression — refreshing in our post-truth era.

At the time of Euripides, twenty-five centuries ago, there was neither journalism nor social media. Parchment and tablets were expensive commodities. As a result, there were very few written works. People learned the news from the agora, the theater, and public assemblies, where they met someone who had witnessed the events. There were historians as well, such as Thucydides, who wrote detailed accounts of important happenings.

Trojan Women was performed for the first time at the Dionysia Festival shortly after its composition in 415 BC. Some consider it the first anti-war play in recorded history. It was written by a man and played by men. According to actor and director Martha Dusseldorp, “Women had the hardest times, and the Greeks knew it.” Ben Winspear adds, “What is extraordinary is that in that era, in which heroes were so venerated, Euripides chose to wipe them out of the picture and instead concentrated on the people who are most affected by these circumstances.”

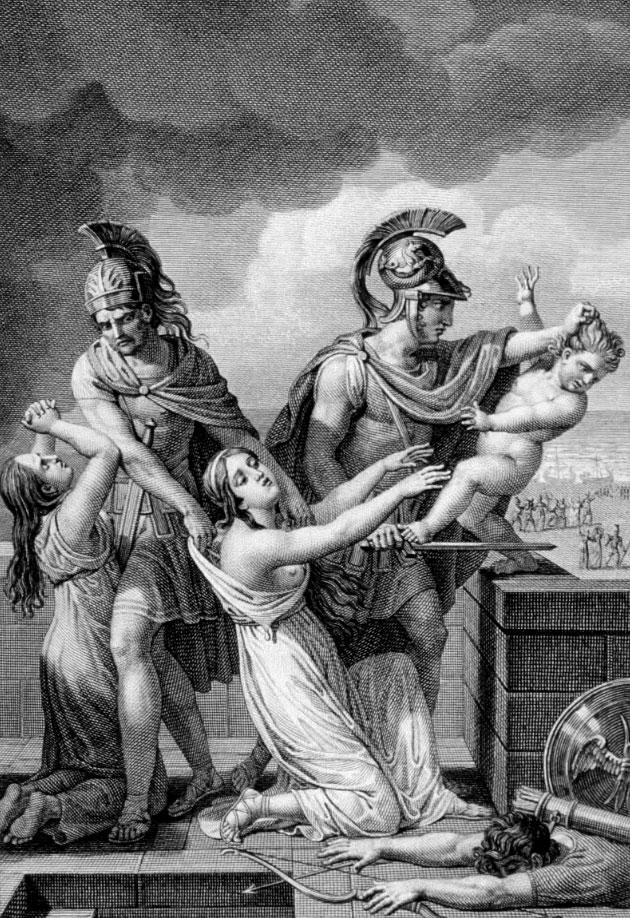

The women and children of Troy suffered during and after the war. They lost their dear ones, their homes, their status. Many were enslaved by the Greek victors. Hecuba was Troy’s queen, Cassandra her daughter, and Andromache her daughter-in-law, the widow of the Trojan hero Hector. The Greek heroes of war had no qualms about enslaving the three of them following their victory. The Greek Menelaus not only promised to kill his wife Helen for leaving him, but also the only heir of the Trojan dynasty, a child. Euripides sees the murder of a child for fear of dynastic revival as a worrying and particularly pernicious innovation.

Euripides dared to represent the powerful reflecting on their actions

For there to be suffering victims, there must also be perpetrators. Euripides judged them in this play. And their fall into decadence is evident, as what we now call the narratives — that of the Athenians and that of the Trojans — expose how different perspectives account for the same historical events, each, of course, to its own advantage.

Two and a half millennia later, we can still shudder in grief, fear, frustration, and despair at the plight of these women. We can imagine the destruction of Troy. We’ve seen so many catastrophe movies in the mold of The Day After. Have we now become immune to piles of rubble? Philosophers wrote entire books about the meaning of ruins. Today, we witness these things every day on TV. Euripides’ tragedy shows us the destruction of an entire city.

Allow me to borrow the words of Alan Shapiro’s introduction to the Oxford edition of Trojan Women: “The theme is really a double one: the suffering of the victims of war, exemplified by the women who survive the fall of Troy, and the degradation of the victors, shown by the Greeks’ reckless and ultimately self-destructive behavior. Trojan Women gains special relevance, of course, in times of war. Today, we seem to need this play more than ever.”

Shapiro discusses why Euripides lost the theater contest that year to a now-forgotten playwright. The likely reason: Euripides hit a nerve. The play premiered the same year Athens raided the island of Milos, slaughtering and enslaving its population for choosing neutrality. Athenians didn’t want to hear about the desperation they were causing in expanding their hegemony. What hegemon wants to hear that?

According to historian Jean-Pierre Vernant, Greek tragedy is extraordinary because it puts dramatic events of the past before our eyes. “In a way,” says Vernant, “it is the city itself that plays out the events, and it offers a problematic line of questioning to the audience without providing any solution.” In tragedy, events unfold with a sort of internal necessity. This is mimesis — a simulation, in the same sense we use the term in physics. Tragedy constructs a chain of events that leads to an apparently inevitable catastrophe.

The bravery and grief of mothers

Fast forward to modern times. Enter Bertolt Brecht, who wrote Mother Courage, another anti-war play, subtitled Chronicle of the Thirty Years War. It premiered in 1941 in Zurich. Brecht, then in exile in Sweden, did not write for amusement but to awaken the public to the grim reality they faced. What he called epic theater is the opposite of what we usually expect: not a divertimento, not an escape, and certainly not catharsis.

Epic theater is a form of didactic drama presenting a series of loosely connected scenes that seek to avoid the effect of illusion, often interrupting the storyline to address the audience directly with analysis, argument, or documentation. Brecht, quite literally, wished to block the public’s emotional responses and to hinder its tendency to empathize with the characters and become caught up in the action.

Yet if we think of the post-truth era, we might see the media doing just the opposite: stoking emotional response to override thought. With the pervasiveness of mis- and disinformation, we may ask ourselves what is the “more real” reality of a play — and where journalism now sits in this arena. What is the role of illusion in the media, as everyone scrambles to control the narrative? Do we even see the truth, or are we still captives of Plato’s cavern?

Perhaps the distinction between reality and narrative can be found in yet another drammaturgo, a theater writer.

In 1918, Luigi Pirandello wrote a short story titled “Quando si comprende” (simply titled “War” in English). Here, the clash between patriotism and personal grief is brought sharply into focus. One character, at first, insists that children belong to their country, not their parents. Since his son wrote that he was happy to serve, the father claims he won’t grieve his death. But a mother asks simply, “So is your son not dead?” At that moment, the man realizes the truth and breaks down sobbing. Feeling, too, teaches. Emotion can provoke critical thought, just as Brecht’s estrangement techniques do.

We are torn between “what must be done” for some ideal — sovereignty, democracy, or another abstraction — and our own subjective experience of care and grief for those we love. Moreover, in consuming media today, we see that democracy means different things to different people. Perhaps there are no universal values. Perhaps those we thought were universal are not.

In Euripides’ Trojan Women, the tragedy of women and children suffering in the aftermath of war is a testament to the human cost of conflict. Brecht’s Mother Courage shows the harsh reality of profiting from war, often at great personal loss. Both works highlight the cyclical nature of violence, where victors’ narratives overshadow the pain of the defeated, who in turn are driven to rebel. Pirandello’s story echoes this too: the inner collapse of someone who tries to uphold the patriotic narrative but is undone by grief.

As we witness the unbearable suffering of civilians in Ukraine and Palestine, we are reminded that their stories often go unheard amid the din of geopolitical agendas. The devastation in these places reflects a grim continuity with the themes expressed in the works of Euripides, Brecht, and Pirandello: the exploitation of the vulnerable, the dehumanization of the “other,” and the moral ambiguities that ensnare individuals in the machinery of war. Brecht calls us to engage critically, not retreat into complacency. Just as the characters in Trojan Women and War are torn between duty and loss, so must we confront the true cost of modern warfare. In a world where truth blurs with propaganda, these ancient and modern voices urge us to act — for peace, justice, and the recognition of our shared humanity.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment