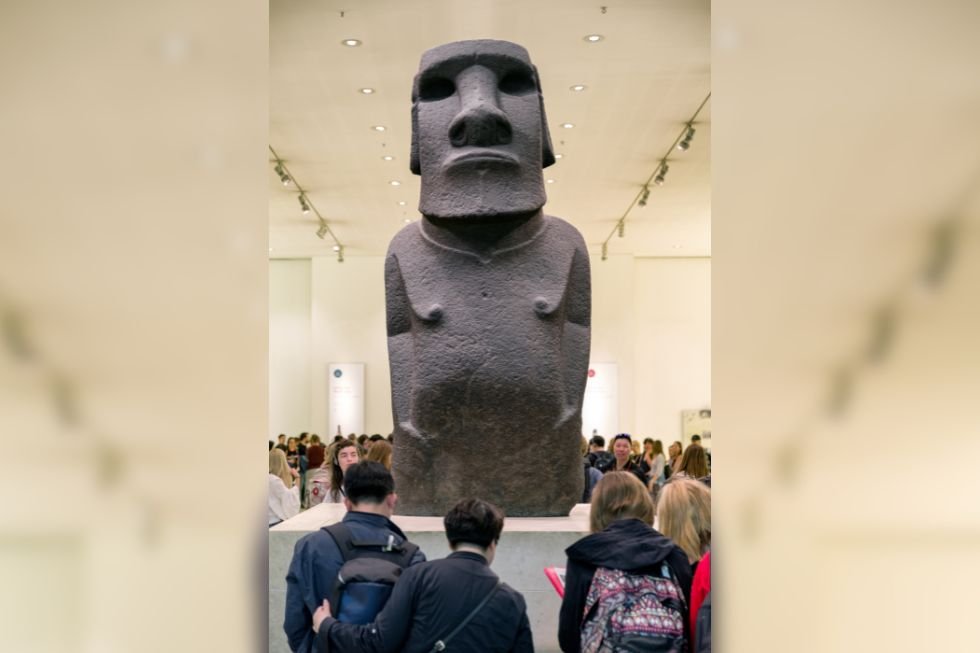

About 3,700 kilometers off the Chilean coast, on one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world, stand the moai of Rapa Nui. Moai refers to the large, monolithic stone statues of deified ancestors on Easter Island in Eastern Polynesia. European explorers first visited this island in 1722, and it now belongs to the South American country of Chile, just as Hawaii belongs to the US and French Polynesia belongs to France.

Carved between the 11th and 16th centuries AD, these towering stone figures act as guardians of the island and enduring symbols of Rapa Nui culture. Yet one of the most important moai, Hoa Hakananai’a, is missing. Like the Elgin and the Amravati marbles, this moai rests in London’s British Museum. Understandably, the moai is the subject of a heated debate that calls into question far more than the fate of a single statue.

For the people of Rapa Nui, the moai in the British Museum is not just art — it is ancestry, spirituality and history carved into stone. Hoa Hakananai’a, the name for this moai, once stood at Orongo, the island’s ceremonial village, where it became associated with the tangata manu ritual that was an annual competition to secure leadership without war.

To the indigenous people of Rapa Nui, the moai in general and Hoa Hakanaia’a in particular embody peace. For many, the removal of Hoa Hakanaia’a in 1868 by a British expedition feels like the theft of a relative. “Allowing the British to hold onto this piece of our history,” says Rapa Nui’s mayor Pedro Edmunds Paoa, “is like keeping our family away from us.”

The British case for retaining foreign cultural treasures

By law, the British Museum cannot return objects in its collection to their original sites. The return of Hoa Hakananai’a, aside from being unlawful, could set off a wave of global repatriation claims. Laws aside, such a case would run the British Museum dry. As any visitor to the museum knows, this venerable British institution is “home” to thousands of artifacts gained through colonial efforts or expeditions that mimicked the manner of the expedition that resulted in Hoa Hakananai’a standing in the British Museum.

Many cultures around the world see the possession of their cultural treasures in the British Museum as “theft,” and the Greeks have been demanding a return of the Elgin Marbles for decades. On December 4, 2024, a former advisor to the Greek government told the BBC that a deal to return the Parthenon Sculptures — what the Greeks call the Elgin Marbles — was “close” but, as of today, they still remain in the British Museum.

The British Museum not only makes a legal case for retaining foreign treasures but also a public interest argument. It argues that keeping the statues is in the world’s best interest. The British argue that their prized museum is a global public good where world heritage is preserved and shared. Anyone from around the world can visit the British Museum for free or see the museum’s treasures online. The Hoa Hakananai’a moai would not be accessible to the world were it to return to remote Rapa Nui.

Museums in richer countries, often former imperial powers, make this argument that foreign cultural treasures are better off with them. Were the treasures to return to their native lands, they might be damaged or destroyed. Humanity would lose them forever. These treasures might also be stolen and sold on the black market, ending up in private hands. Public access to these treasures would then be lost. Ironically, world heritage is best preserved in the British Museum or the Louvre, which have decades of expertise in preserving and displaying cultural treasures of the past.

If every great work of art remained in its cultural home, how could it be shared with so much of the world? How would people around the world have the chance to learn about a culture that they were unlikely to come in contact with?

The case for returning cultural treasures

The British argument for retaining Hoa Hakananai’a, the Parthenon Sculptures and the Amravati Marbles for global public benefit over time calls into question the very meaning of “cultural preservation.” Is a culture preserved if one of its symbols is looked after very well in a wonderful museum and kept in good condition? Or is a culture preserved when the symbol is part of a living tradition in the society where it is the warp and woof of the culture?

If Hoa Hakananai’a is just a historic stone statue, then the British Museum is perhaps the best place to preserve this wonderful art. If Hoa Hakananai’a is still a part of the culture of the indigenous people of Rapa Nui, then perhaps the arguments of rightful ownership, collective dignity and cultural perpetuation trump the legal and public benefit arguments of the British Museum. Hoa Hakananai’a is a moai venerated by the people of Rapa Nui in a way it is not by the most interested, invested and culturally sensitive visitors to the British Museum.

When colonization, slavery and disease nearly destroyed the Rapa Nui population in the 19th century, the moai remained steadfast symbols of identity. Losing Hoa Hakananai’a meant more than losing a statue — it meant losing a part of the island’s indigenous population’s survival story. There is an argument to be made that Hoa Hakananai’a is integral to the identity of the people of Rapa Nui.

A tricky and complicated issue

As you can see above, there are good arguments for both retaining and returning the Hoa Hakananai’a moai. That is why the remote islanders and the British have been disputing ownership for decades. Delegations have traveled back and forth from Rapa Nui to London, but the issue is unresolved. The British have made promises of collaboration, but Hoa Hakananai’a still remains in London.

Perhaps the answer is not as simple as “returning” or “retaining” Hoa Hakananai’a. Some Rapa Nui leaders have even floated the idea of keeping Hoa Hakananai’a in London as an ambassador, as long as the British acknowledge that it belongs to Rapa Nui.

The Rapa Nui community itself is divided over the moai’s fate. While many argue passionately for its return, others recognize that the British Museum may offer the best conditions for its preservation. On Rapa Nui, hundreds of moai remain exposed to wind, saltwater and rain. In the past, many fell and all have already suffered damage.

By contrast, Hoa Hakananai’a is protected, conserved and well-positioned in the British Museum to share Rapa Nui culture with a global audience. Some form of the status quo is perhaps the most sensible path forward. Cultural preservation takes multiple forms: The moai on Rapa Nui island embody ancestral presence, while Hoa Hankananai’a in the British Museum serves as the island’s cultural ambassador to the world.

The Hoa Hakananai’a debate points to a broader tension concerning the repatriation of cultural treasures. Colonial theft is an undeniable truth. Naturally, many people want to right that wrong and return these treasures to their native lands. Some play the morality card and try to guilt descendants of their former colonial masters or imperial adventurers into returning these treasures.

Yet the practical question of returning these cultural treasures is more complex. If every piece of art, sculpture or cultural artefact taken during the height of the European empires were repatriated, global museums would be stripped of their collections. More importantly, millions of people would lose access to cultural traditions that differ from their own. As pointed out above, these artifacts may be destroyed or end up in private collections, with the public losing access to them forever.

In the case of Rapa Nui, the return of Hoa Hakananai’a would not significantly affect the island’s tourism economy. Tourists can and do visit the hundreds of moai still guarding Rapa Nui’s shores. The return would certainly deprive millions of British Museum visitors from around the world to learn about a culture that they might never have heard of or ever explored.

The operative question is not simply whether Hoa Hakananai’a should stay or go, but what does cultural preservation truly mean today? Is heritage best preserved when artifacts remain in their place of origin, fulfilling their intended spiritual role, or when they are safeguarded and shared with the world? In practice, both approaches matter — Rapa Nui can retain its sacred moai and spiritual traditions, while Hoa Hakananai’a extends the island’s cultural reach far beyond its shores.

In the case of Hoa Hakananai’a, the best solution is what some islanders themselves suggest. The British Museum should continue housing the moai in its fantastic building in London, but the British government should acknowledge the indigenous islanders’ ownership of the statue. Until the British Isles and Rapa Nui island can come to an agreement, Hoa Hakananai’a remains a symbol of a larger, unresolved question: Who has the right to control cultural treasures — global museums that house them, or the communities that created them?

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment