US Treasury securities, with more than $33 trillion outstanding, comprise the world’s largest government bond market. Yields on those securities serve as benchmarks for interest rates around the world, setting the baseline for the cost of borrowing for everything from dollar-denominated borrowing by non-US governments to corporate debt. So, if the Treasury market is in trouble, its effects can ripple throughout the international debt markets and, therefore, the entire world economy.

How Treasury rates affect other rates

Since US public debt is widely regarded as a “risk-free” asset, it is taken as a baseline for pricing other, riskier debt investments.

Pricing of newly issued corporate bonds is usually expressed as a premium to US Treasuries. For example, if you are a BBB-rated US corporation, you currently would need to pay 1.6 percentage points more than the yield on 10-year US Treasury bonds, currently at 4%. Hence, the corporate bond would yield 5.6%).

The same applies to non-US governments issuing debt. Recently, the Philippines (rating: BBB+) sold new 5½-year debt. The bonds were priced to yield “T+144bps”, meaning “Treasury yield plus 144 basis points,” or 1.44 percentage points. Lower-rated State of Mongolia (B3, equivalent to B-) had to offer a spread of 4.25 percentage points over Treasuries for a total yield of 8.75%.

The yield premium over Treasuries is also known as the “spread.” Here you will find a table explaining the credit scale used by rating agencies.

The entire world’s debt is priced off Treasury securities. If the yield for Treasuries goes up by one percentage point, most borrowers of US dollars will see their yields increase by the same amount. With more than $300 trillion in global debt outstanding, a one percentage point increase in interest rates would cost borrowers $3 trillion (which is larger than the GDP of all but the top seven nations).

Given their importance, we need to understand how Treasuries are created, traded and treated.

How the sausage is made

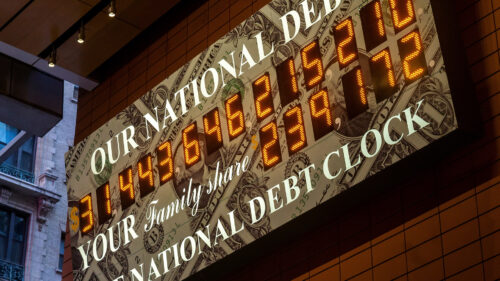

Treasury securities are born out of necessity—the need for the US government to raise funds. Since the government spends more than it raises in taxes, any shortfall must be filled by selling debt. For the 2022–23 fiscal year, the deficit amounted to nearly $1.7 trillion.

In addition to plugging the hole torn by deficits, the US government needs to refinance existing debt coming due — which is a lot. An astonishing 85% of Treasury debt issued in 2023 is due within one year or less. This leads to constant refinancing needs. 4-week Treasury bills, for example, need to be refinanced twelve times per year.

Despite the annual fiscal deficit being “only” $1.7 trillion, the gross financing needs for November 2023 alone added up to $2.37 trillion.

To figure out how much debt to issue, the Congressional Budget Office drafts a “Budget and Economic Outlook,” typically each January, and updates it in August. Treasury officials meet quarterly with the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, comprising senior representatives from banks, broker-dealers, hedge funds and insurance companies. The committee then issues a report to the Treasury Secretary with recommendations on debt issuance for the coming quarter, culminating in table with a recommended financing schedule. The Treasury department subsequentlyissues a tentative auction schedule. This way, market participants can anticipate future supply and plan accordingly.

Treasury securities come in three main categories, classified by time to maturity: Treasury Bills (one year or less, namely 4-, 8-, 13-, 17-, 26-, and 52-week), Treasury Notes (2-, 3-, 5-, and 10-year) and Treasury Bonds (20- and 30-year).

The bills do not have a coupon, or interest payment. Instead, are sold at a discount to their face value. For example, a 52-week bill would be issued at 95%, so that the ultimate yield would be 5.26%. All other Treasury securities carry a coupon.

All issues have a fixed rate, except for the 2-year note, which can be issued with either a fixed or variable rate.

In addition, 5-, 10-, and 30-year notes and bonds also come as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS). Unlike other Treasury securities, where the principal is fixed, the principal of a TIPS receives an inflation adjustment over time. For example, the latest 5-year TIPS has a coupon of 2.375%. On top of that, the principal gets adjusted for inflation in regular intervals, compensating the owner for the loss of purchasing power.

How Treasuries are sold

New Treasury securities are sold via auctions. Institutions submit bids, stating which minimum yield they are willing to accept. The Treasury then fills all bids, beginning with the lowest yields, until the entire auction amount is sold (i.e., it uses a Dutch auction). All successful bidders are then awarded the same final yield.

Indirect bidders do not have accounts with the Treasury and must submit their orders through primary dealers, who act as intermediaries.

Primary dealers are a select group of banks and financial institutions that are obligated to bid in Treasury auctions. If no other buyers show up, primary dealers will end up buying the entire auction. In theory, this could amount to $90 billion or more. However, in March 2020, the Federal Reserve introduced a lending program, the so-called “Primary Dealer Credit Facility,” where Primary Dealers can obtain loans against collateral (consisting of the Treasury securities they just bought). The amount of borrowing is unlimited, thereby eliminating the possibility of a failed auction.

This is an important piece of information to understand: US Treasury auctions cannot fail. The Federal Reserve will lend unlimited funds to private sector institutions to absorb any unsold securities. However, the Federal Reserve does not cover any price risk; if interest rates were to rise rapidly, bond prices would decline, creating losses for financial institutions holding them. This effect was seen in March 2023, when Silicon Valley Bank was brought down by losses on Treasury securities and other bonds usually deemed “high quality liquid assets.”

The secondary market

Buying a Treasury security in an auction is also referred to as the primary market. Once a Treasury security has been issued, trading in the secondary market begins.

Trading volume in the secondary market is impressive. According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, more than $840 billion worth of Treasury securities were traded daily during November 2023. On busy days, trading volume is likely to exceed $1 trillion, equal to 3% of the total amount outstanding.

On top of that, futures contracts on those bonds are being traded. A futures contract is a trade where the price between buyer and seller is set, but the settlement is made at a specified date some time later. Most futures positions are unwound before settlement.

The average daily volume for the most popular contracts (10-year, 2-year and 5-year) exceeded 13 million in November of 2023. Multiplying the number of contracts traded by their face value of $100,000, the total value of those futures traded amounted to more than $642 billion.

Maintaining this level of market liquidity is important because it makes sure that large buy or sell orders can be absorbed without much impact on price.

The repo market

If you are in a financial pinch and need to borrow money, you may go to a pawn shop. A simple promise to pack back the loan will not convince the store clerk. However, you can use a gold watch as collateral. The store clerk keeps your gold watch until you pay back your loan.

Treasury securities are considered the safest and most liquid investment. This makes Treasuries the perfect collateral for borrowing money.

After the 2008 global financial crisis, unsecured lending (without collateral) all but disappeared. Even banks do not trust each other anymore.

Borrowing money by using Treasury securities is called a repurchase agreement, or short “repo”. In a repo transaction, the borrower agrees to buy back the securities used as collateral at a later date. The repurchase price will be at a slight premium, compensating the lender for lost interest. The time frame for these transactions is usually very short, often overnight.

Here, too, the amounts involved are mind-boggling. In November, the average daily repo financing reached a stunning $5.2 trillion, comprising $4 trillion of Treasury securities.

As if this wasn’t enough, a reverse-repo market exists where the Federal Reserve lends out Treasury securities in exchange for cash, with a peak volume of $2.5 trillion.

Who owns Treasuries?

“Somebody” needs to own (and keep buying) US federal debt. A look at the the owners of Treasuries reveals that only two out of five groups are price-sensitive: foreign and domestic private institutions. The other three groups are the US government trust funds, the Federal Reserve and foreign official holders — central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

US government trust funds include like the Social Security and Medicare. These funds are “captive” buyers. They are obligated to invest in Treasuries, regardless of the price.

Central banks, including both the Federal Reserve and foreign central banks, are also insensitive to price. They acquire securities for reasons other than profit maximization. Their purchases are motivated by monetary policy (Federal Reserve) or exchange rate policy (foreign central banks).

Foreign entities hold $6.7 trillion worth of Treasury securities, of which foreign official accounts hold more than half. Among the largest holders by country are traditional export countries like Japan ($1 trillion) and China ($0.8 trillion). As most internationally traded commodities and goods are invoiced in US dollars, the exporter ends up with excess dollars. To prevent its exchange rate from appreciating, their central bank then needs to absorb those dollars.

This has important implications; as long as non-US nations produce more goods and services than they consume, they will have positive trade balances, and hence US dollar inflows (that often get absorbed by a central bank). As long as the US consumes more than it produces, a trade deficit implies more money leaving the US than coming in. In other words, the US is exporting Treasury securities. The export of debt is the mirror image of its balance of trade. Financial flows must match flows of goods and services.

According the Polish economist Kalecki, a nation’s economy consists of four sectors: households and corporations (the private sector), the government and the foreign sector.

If the foreign sector has a surplus, domestic sectors must have a deficit. This could be either the government, or the private sector, or both. In the case of the US, the large and growing trade deficit therefore requires a large and growing fiscal deficit.

Only if Congress stepped in and put the brakes on government spending would the fiscal deficit shrink. This, in turn, would force a reduction in the trade deficit. Such a reduction is characteristic of a recession, as US consumers are forced to cut consumption, a lot of which consists of imported goods.

Foreigners would then cut their purchases of US securities. But now, the need for foreign financing of US debt is reduced since the fiscal deficit was addressed.

The numbers may seem scarily large, but the Treasury market is far from being at the edge of a cliff.

[Anton Schauble edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment