Audrey Hepburn’s life, which came to an untimely end on January 20, 1993, was much more than a brilliant film career.

Audrey Hepburn’s philosophy of life was direct: never in flight before contemporary difficulties. Her vision was straight and simple — that of a humble utopia that began and percolated in her psyche, for a noble cause: the children of our world.

If gentle nature and great courage rarely manifest in one individual, she was a sublime exception. No wonder that she empathized with children — and they with her. She didn’t just work for the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), she was its “fair lady” with a heart of gold, a true friend, a powerful and eloquent advocate.

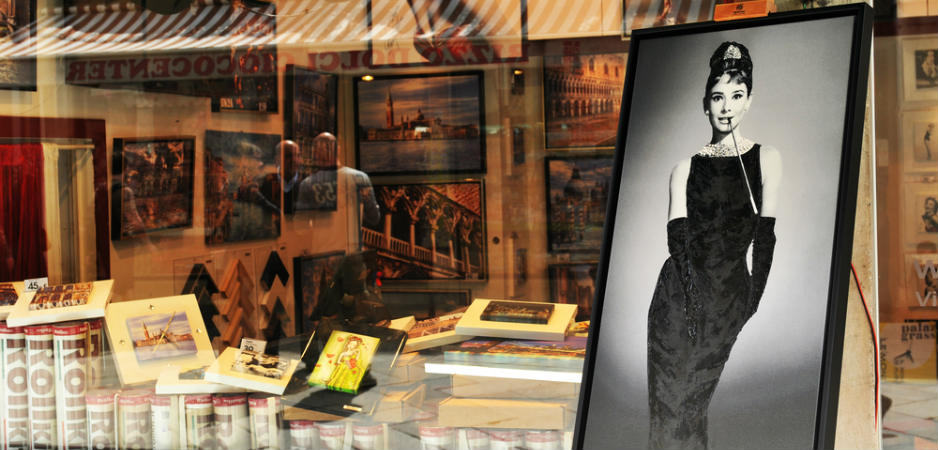

Hepburn’s identity was that of an elfin charmer, a brilliant Hollywood star whose allure was unlike anyone else’s. She was simply different — a pure magic on celluloid, endowed with a regal elegance, a romantic magnetism and a subtle transcendent quality. Hepburn — née Edda Kathleen van Heemstra Hepburn-Ruston, on May 4, 1929, in Belgium — was, in reality, far above the vain pursuits of traditional Hollywood beauty. In any given situation, she could be Holly Golightly — her famous role in the 1961 film adaptation of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s — fragile, exotic, liberated, loony bohemian. It was a mix that transcended all gloom.

Versatility was her forte. A trained dancer, Hepburn’s physical fragility was an unusual contrast with a certain ancient wisdom — an amalgamation that dazzled against her romantic leads, who were often men almost twice her age. In Funny Face (1957) she was 28, Fred Astaire 58; in Sabrina (1954) she was 25, Humphrey Bogart 54; and, in Love in the Afternoon (1957) she was 28, Gary Cooper 56. Hepburn was the perfect free-spirited Eliza Dolittle in My Fair Lady (1964); a natural princess in Roman Holiday (1953), where she played a royal heiress who pretends to be a commoner and falls in love with a newspaper reporter (Gregory Peck).

Her performance in Alfred Hitchcock’s Charade in 1963, alongside Cary Grant, delighted with elegance and histrionic finesse. In a characteristically humorous scene, Hepburn puts her finger inside Grant’s famed cleft skin and wonders, “How do you shave in there?”

Center Stage

Hepburn was synonymous with elegance, her diminutive frame and her pensiveness riveting the cinemagoer’s attention against the men on screen next to her. She was visually magnetic, possessing a certain quality of not being happy, yet happy at the same time. As Billy Wilder, who directed Hepburn in two films, recalled: “You looked around and suddenly there was this dazzling creature looking like a wild-eyed doe prancing in the forest. Everybody on the set was in love within five minutes.” This was, perhaps, the secret of her cinematic success in holding the center stage.

While Roman Holiday was a charming reverie, The Nun’s Story (1959) was all about convent life, and Wait Until Dark (1967) a suspenseful, adventurous medley, just as Breakfast at Tiffany’s was a blustery story of a naïve young girl sought by affluent, vacuous men. War and Peace (1956), where Hepburn played Natasha, was a stunning recreation of Russian history. This was her fabulous range, awesome repertoire and talent. As Alan Arkin, who “terrorized” Hepburn in Wait Until Dark, once said that “she has the ability to elevate every character she plays to a higher level than was originally conceived.” Hepburn lived her roles to the full, without ever overdoing or underplaying any facet of expression or character. If this wasn’t a triumph for creativity at its zenith, what is?

Hepburn was marvelous in Love in the Afternoon, where her puppy admiration for an aging playboy was no mere flirtation. Her portrayal was delicate, a visage of sheer brilliance. She’d do it all so effortlessly. More than anything else, Hepburn transcended Hollywood phoniness, not to speak of the less savory aspects often attached to her profession. As Robert Wagner (who appeared with Hepburn in the 1987 TV movie, Love Among Thieves) eulogized: “She was in the moment — always. Those close-ups of her when she looks and you see into her eyes, there is no diffusion. You are looking into her soul and spirit. She had a great soul and she had great spirit of life.”

Humanitarian Calling

Hepburn’s humanitarian work as a UNICEF, first as special ambassador and then as goodwill ambassador — a calling she sought out herself and remained devoted to until her death in 1993 — first took off with her mission to Ethiopia in 1988, where chronic drought had brought on a devastating famine. Hepburn made heartfelt pleas to the media, giving over a dozen interviews a day. She visited areas bereft of water, basic health-care facilities and sanitation. She made earnest attempts to use her fame to draw the world’s stoical insensitivity to the cauldron of human suffering that was Ethiopia. There was no rhetoric. Hepburn simply felt that it was her call — not just a role.

In 1989, she took part in Operation Lifeline in Sudan, ravaged by a bloody civil war. In the course of her mission, Hepburn visited dozens of refugee camps and witnessed first-hand the relief measures, including delivery of life-saving drugs and food packets. Hepburn’s dedication took her from the deserts of arid Africa to the muggy slums of Asia, to Bangladesh, Kenya, Guatemala, Venezuela, Vietnam, Somalia, among others — wherever there were children living in abject poverty, with no access to food, water or basic education.

Back in the United States, Hepburn testified in front of the House Select Subcommittee on Hunger in 1989, and again two years later to call for a boost in aid to Africa. Her dedication won her America’s highest civilian honor — the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Hepburn was also a posthumous recipient of the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, an Oscar given to an “individual in the motion picture industry whose humanitarian efforts have brought credit to the industry.” But honors and accolades were only secondary to Hepburn — her mission to help the needy, the deprived, the disadvantaged, especially children, irrespective of their color, faith or belief, was everything to her: “I have been given the privilege of speaking for children who cannot speak for themselves, and my task is an easy one, because children have no political enemies. To save a child is a blessing: to save a million is a god-given opportunity.”

Hepburn always thought that her own life had been much more than a fairy tale, saying that “I’ve had my share of difficult moments, but whatever difficulties I’ve gone through, I’ve always gotten the prize at the end.” With characteristic, quiet modesty she assessed the secret behind her great stardom: “I decided, very early on, just to accept life unconditionally; I never expected it to do anything special for me, yet I seemed to accomplish far more than I had ever hoped. Most of the time it just happened to me without my ever seeking it.”

Hepburn never made it big in the gossip columns — a great achievement. Her two marriages failed, yes. Yet her sparkling warmth and refined, dignified personality prevailed over the clutter of the yellow press. Even cruel cancer could not wobble her; she carried on spiritedly making this world a better place for those less fortunate than herself. When Audrey Hepburn died, on January 20, 1993, in Switzerland, aged 63, she left a void palpable across the world. This was the true apogee of her life — that of true respect bestowed on her with unequivocal adoration that would have meant far more to her than the Oscar nominations and statuettes.

Hepburn was ethereal — the Asteroid 4238 Audrey is named after her. But she was also real. She wore her badge of love and compassion with a purpose, and for a higher purpose too. There won’t be another like her again.

*[Update: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Audrey Hepburn had starred in On the Waterfront (1954).]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.