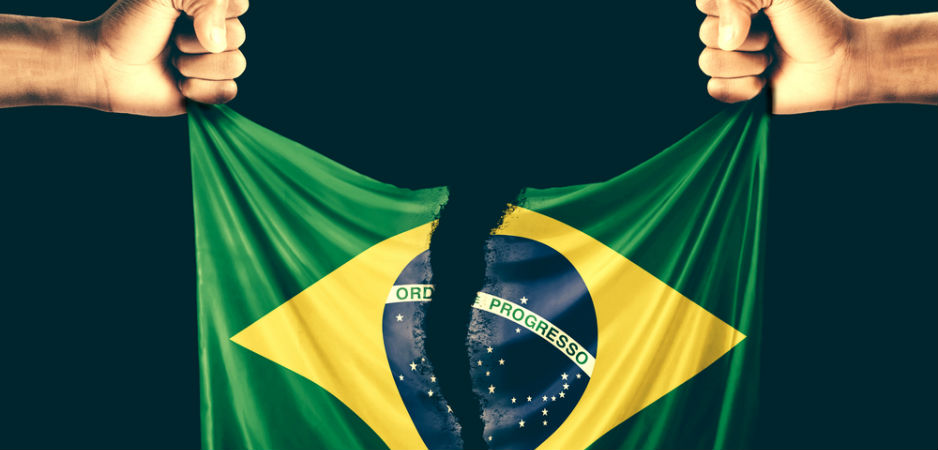

Historical and structural problems lead to corruption in Brazil.

In Brazil, two cars drive on a highway in opposite directions. When crossing each other, one of the drivers frantically flashes the headlights. This is a scenario that nearly every Brazilian will understand: It means that police are ahead. The message is something along the lines of: “In the next few minutes, it is imperative that you do not exceed the speed limit.” The general feeling is that the police are not there to ensure everyone’s safety, but rather serve as a nuisance.

On social media, I interact with roughly 6,000 friends and followers—whatever that means. It’s a way for me to observe the variety of social archetypes in the world. Intolerance and fury are abundant. Social media users serve as virtual watchdogs, monitoring the scandals of the current government. In principle, such harshness toward corruption is a good thing. But I try to invite them to reflect on their own behavior. Do they flash their headlights on the highway?

There is also a group of people who argue that if other governments and parties have done their share of wrong, then everything done by the current administration should be pardoned. If nobody was punished before, why start now? They want the same harshness—or lack thereof—but they forget that time doesn’t go backward. Their line of reasoning makes no sense either. One cannot justify a murder, for example, because Jack the Ripper came before them. In this profound relativism of wrongdoing lies an undeniable confession of guilt.

Where Does Corruption Stem From?

In the first document produced in Brazil, Pêro Vaz de Caminha, a Portuguese knight, announced to King Manuel I of Portugal the discovery of new land. He seized the opportunity to address the monarch and asked for a pardon of his son-in-law, who had been banished to Africa. Political patronage was present from the very beginning of Brazilian history. It came from the colonizing country. There was also strong corporatism, giving more participation in decision-making to certain interest groups than to others.

But historic fatalism cannot explain or justify the levels of corruption we see in Brazil. Unfortunately, corruption has become a much more complex phenomenon, and public indignation could grow. It is also much less acceptable than moral relativists would like everyone to believe. There are, of course, cultural roots that help explain corruption in Brazil. However, nowadays these reasons are mixed with deep structural issues.

First, it is necessary to understand the vicious cycle that rules our society: People do not trust Brazilian institutions, and without that trust, institutions match citizens’ worst expectations. There is nothing to improve when there is no hope of improvement. Cruel intentions and general inefficiency become the rule rather than the exception.

In his book, Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences, Norwegian social and political theorist Jon Elster once said: “Institutions keep society from falling apart, provided that there is something to keep institutions from falling apart.” In Brazil, there is little to keep institutions from falling apart.

On the highway, one driver warns another about the police because he doesn’t trust law enforcement, and there are legitimate reasons not to. Facing the inevitable interaction with the policemen ahead, the other driver has already internalized the strong possibility of having to bribe the officers. It is as natural as perverse. Corruption becomes an element of daily life, and nobody seems to realize how it contributes to broader problems.

Although not a general rule, corruption on an individual level is generally more tolerated even when people despise corruption in others. It’s as if those corruption cases reported by media were the only kind to exist, but they’re not. As for the policeman, why would he act in another way if the “system” is already like that—especially if he’s labeled a corrupt officer anyway? And if the people above him do the same thing, then why are his actions so bad?

In a way, this is what has happened to our political system. Of course, there are honorable people who work in Brazilian politics. But as time has gone by, political patronage has become a natural part of it. When the special assembly wrote a new constitution in the 1980s, politicians established what we refer to as the “Saint Francis logic”—for it is giving that we receive. The relationship between the government and congress became just that.

In every political system, it is admitted that the use of some “grease” is needed to lubricate the engines of power. But in Brazil, the system has a destructive appetite. And the excess of that “grease” threatens to make the system completely collapse. The incorporation of political patronage gave birth to a perverse order where clientelism is the rule and all kinds of schemes are admitted, affecting Brazilian society as a whole.

The Ruling Party

To accept that “it has always been like this” is ultimately admitting that “it will always be like this.” It is a mistake to share that atavistic belief, because believing this defines how politics works and how the economy is managed. Over the past decade, this is exactly what has happened in Brazil.

The Worker’s Party did not invent corruption, but it has incorporated it in some aspects of governance. It is regrettable that party members have built on corruption to the point of perfection. The distribution of executive jobs in state-owned companies and the corruption of public bid processes were treated as natural. There is no ideological program anymore, if there ever was one. Realpolitik has become natural.

The Worker’s Party did not invent corruption, but it has incorporated it in some aspects of governance. It is regrettable that party members have built on corruption to the point of perfection. The distribution of executive jobs in state-owned companies and the corruption of public bid processes were treated as natural. There is no ideological program anymore, if there ever was one. Realpolitik has become natural.

But there is a limit to everything. After all, the excessive use of a product can damage it. We cannot say with precision what really happened in terms of corruption in past administrations. When it’s carried out well, corruption is not particularly noticeable. But it does beg the question: Why did the Worker’s Party not investigate and punish the crimes its predecessors committed? After 14 years in office, the ruling party has exhausted both itself and the system. It has not done anything to reinforce the limits of what we can call “acceptable”—it has actually surpassed them.

The biggest mistake the party made was letting itself become engulfed by the idea that corruption is a natural nuisance. It did not push for much-needed reforms that could have led to the cultural transformation the party always called for. If the Worker’s Party was once the moralist of Brazilian politics, it now claims to be a victim of false moralists. The whip its leaders once held now seems too harsh to endure.

The removal of President Dilma Rousseff and her party from office would not put an end to corruption in Brazil. We must stop looking at corruption as something natural. That deafening demand becomes harder and harder to ignore. Neither radicalization, nor relativism can contribute to cultural change. We must have new, reformist leaders. The problem is that those leaders have not yet appeared. But maybe they’re out there, not knowing why other drivers are flashing their headlights.

*[This article was originally published by plus55, a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Photo Credit: Adao / NikoNomad / Shutterstock.com

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

We bring you perspectives from around the world. Help us to inform and educate. Your donation is tax-deductible. Join over 400 people to become a donor or you could choose to be a sponsor.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.