In the eighth century AD, a North African Muslim population composed of Arabs and Berbers, known as the Moors, invaded and conquered much of the Iberian Peninsula. That is, the current Spain and Portugal. The fact that Portugal expelled the Moors from its territory in 1249, while it took until 1492 for the Spaniards to attain the same, had fundamental consequences in relation to their respective possessions in the Americas.

In Spain, a continuum existed between the reconquest of its own territory from the Moors and the conquest of its new American lands. Indeed, the year 1492 represented the end of the former and the beginning of the latter. Meaning, the defeat of the last Moor enclave in Spain and the “discovery” of a new continent by a Spanish expedition headed by Columbus.

In just half a century

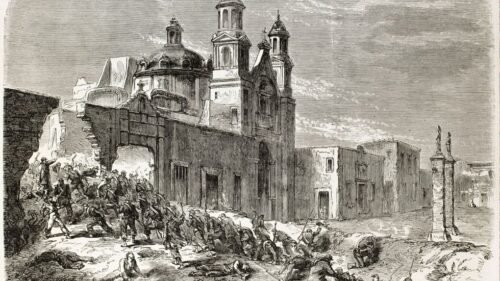

As a result, the spirit of mission that had animated the Spanish life during eight centuries (that of expelling the Moors) simply moved to the other side of the Atlantic. No other European country, without the sense of warfare mobilization and religious combativeness that prevailed in Spain, could have had the energy and the daring to take hold of such an enormous and inordinate geographical space in just a few decades. In just about 50 years, indeed, Spain subdued the indigenous populations, Christianized them, urbanized and populated the new territories, founded universities, put in motion a process of economic expansion and created its ruling institutions.

During that brief period, the Spanish conquerors defeated war-oriented indigenous populations throughout the continent. This included the mighty Aztec and Inca empires in current Mexico and Peru. Meanwhile, their missionaries thoroughly evangelized the native populations. For that purpose, they had not only to master the different indigenous languages but also their meanings and symbols, as this was the only way to make their teachings understandable. After attaining their religious purposes, though, the missionaries simply discarded such knowledge as an expression of paganism.

Urbanization had been an essential part of the Spanish Reconquest of its territory from the Moors. Indeed, every advance upon them had to be consolidated by building cities and towns within a concept of expanding frontiers. Not surprisingly, urban-minded Spaniards brought the same approach to the Americas. Towns and villages would become the tools for consolidating conquered spaces and for integrating the hinterlands to the coasts.

Populating the newly founded towns implied bringing women from Spain. Much has been written about the solitary nature of the Spanish conquerors as the leading cause for miscegenation, with indigenous women being the only females available to them. Undoubtedly, this is true, yet only to a certain extent.

Of the registered 45,327 Spaniards who came to America in the 16th century, 10,118 were women. In other words, there could have been around 20,000 married couples and around 25,000 single men. Moreover, during the first quarter of that century, a third of all the arrivals were women. This entails that half of the men had access to a Spanish wife. These Spanish couples would become the origin of the colonial gentry through endogamous marriages.

As early as 1538, the Spaniards founded the University of Santo Tomas de Aquino in the Dominican Republic of today. It was not only the first in the hemisphere but also among the first 15 within the Spanish world. This institution was followed in 1551 by the founding of the University of Mexico and that of San Marcos in Lima. When these universities came to life, a wide network of schools already existed throughout the region.

In 1545, the 20-year span in which the major mining discoveries in Mexico and Peru took place began. They were to become large-scale operations that put in motion numerous interconnected economic activities. Workers needed housing and stores, while mines required masonry, winches, ladders and huge amounts of leather. Mules and horses were required to move the bullion to mints and to the exporting coastal areas. Plantations and ranches had to be established to supply mining operations and the emerging adjacent towns. And so on, amid a flurry of action.

To administer these territories, the Spaniards created a centralized political structure. From Spain, the Council of the Indies was responsible for the whole, while in America, two main viceroyalties were created: New Spain (current Mexico) and Peru. These viceroyalties controlled smaller administrative units called audiences, which in turn had jurisdiction over governorships. From the beginning, a complex bureaucratic system was put in place.

Meanwhile

Nothing remotely similar happened in Brazil during the same period. This territory was granted to Portugal by a Papal Bull that divided the lands of the New World between the Spaniards and the Portuguese. The fact that Portugal had completed its war of reconquest 243 years before Spain was directly related to this. Indeed, there was no connection between the reconquest of their own territory from the Moors and the conquest and colonization of their American possessions. Moreover, while in the case of Spain an old sense of purpose easily switched from its own land into its newly acquired transatlantic territories, Portugal had ample time to define different priorities. Naval exploration and international trade represented these priorities.

Beginning in 1418, with the incorporation of the Azores and Madeira islands off the coast of Africa, the Portuguese continued south along the coasts of West Africa. Along this descendant route, they established a system of slave and ivory trading posts, without inland colonization. In the late 15th century, they had discovered a sea route to the East around the Cape of Good Hope. In 1510, they founded the colony of Goa on the western coast of India. A few years later, the Malacca peninsula (current Malaysia) became the strategic base for Portugal’s trade expansion towards South East Asia, China and Japan. Subsequently, it built fortified settlements in present-day Indonesia to control the spice trade. The Portuguese Empire of the East, with its capital in Goa, included possessions in all of the Asian sub-continents.

The Portuguese thus had a global reach unknown to the Spaniards (whose sole Asian possession was the Philippines, which became a simple extension of its American Empire through its galleon trade with Mexico, inaugurated in 1565). But whereas the Spaniards had their American possessions under a firm grip, the Portuguese were highly vulnerable in their overexpanded territories. Through a several-decade war between the Dutch and the Portuguese, in the 17th century, the former seized most of Portugal’s possessions in Asia.

A minor concern

While Portugal’s attention was elsewhere, Brazil was of minor concern to them. There, they replicated their experience on the western coasts of Africa: establishing isolated trading posts along the coast, without aiming to penetrate inland. These first five decades, in which Spaniards were making deep inroads into their own American territories, were a period of absolute neglect for Brazil. As a result, impoverished Portuguese male settlers were left to their own devices.

Through an old indigenous practice of incorporating strangers into their tribes through marriage, these settlers were assimilated into indigenous populations. Taking as many “wives” as possible implied, by extension, widening their network of relations with different local tribes. The result of this process was a polygamist society in which the multiple offspring of the settlers ended up being much closer to their native mothers’ way of life than to their European fathers’ way of life.

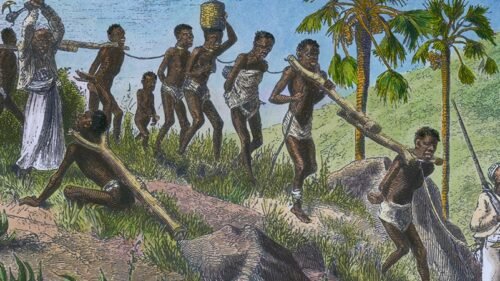

Speaking in the indigenous Tupi language and living under primitive conditions, the descendants of the first Portuguese settlers became a troop of rough adventurers, much closer to plunder than to production. Armed with rudimentary military tools, this amalgam of Europeans and natives transformed itself into a human-hunting society. Their aim, indeed, was to capture and enslave the natives with the purpose of selling them. This happened, basically, in the current state of São Paulo.

After depleting the coasts of their human prey, the Portuguese and their offspring began making inland raids that were to become more and more ambitious and predatory. Preceded by banners, they gathered into huge groups that, for extended periods of time, raided the inland territories. The enslaved indigenous peoples, for whom good prices were fetched, became their main commodity of trade.

The main buyers of this human merchandise were the planters of north-eastern Brazil. Indeed, another pole of Portuguese settlement took shape farther north along Brazil’s coast, where sugar plantations began to emerge. It was undoubtedly a more civilized society, where production and not plundering was the goal.

When France proclaimed its right to take possession of any nonoccupied part of Brazil, the Portuguese Crown was forced to react. In 1549, Portugal appointed its first Governor General in Brazil, with a base in Salvador de Bahia. With sugar exports later followed by precious metals generating increasing revenues, and Crown authorities exerting a larger role, Portuguese America became a much more structured society.

Eventually, it would end up catching Hispanic America in this regard. Moreover, at the end of the colonial period, Brazil surpassed its Spanish American cousins in terms of institutional strength and territorial cohesion. The reforms introduced in Brazil at the end of the 18th century, and the fact that the Portuguese Crown was forced to move there for more than a decade as a result of the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal, were responsible for it. Hence, while at the beginning of the colonial period, Spaniards greatly surpassed the Portuguese in providing structure to their American territories, by the end of that period, the Portuguese outshone them.

Utter lack of curiosity

What both Spanish and Portuguese had in common, though, was their utter lack of curiosity in relation to the indigenous populations that they found in America. The Portuguese were undoubtedly much harsher towards them than the Spaniards, whose laws protected indigenous people. However, the Spaniards’ behavior was more blameworthy. This is simply because they met with advanced civilizations far from Brazil, which was inhabited by primitive tribes. Civilizations, whose scientific advances (particularly in mathematics, astronomy and engineering) and many of their organizational and cultural traits merited to be preserved. However, all the knowledge that they represented was completely and systematically discarded and erased by the Spaniards.

Not surprisingly, nowadays, resentment against Spain is substantially bigger in Hispanic American countries than it is in Brazil towards Portugal. Brazilians, indeed, don’t have a quarrel with their colonial past, whereas much of Hispanic America does. This explains why, in the last few decades, the statues of Italian explorer Christopher Columbus have been taken down from their pedestals in many cities of Hispanic America. For several Latin American countries, this still remains an unresolved contention.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment