For a brief period during the pandemic, the labor market suspended one of its most consequential price signals: physical presence. Productivity was judged less by hours spent in a chair than by outputs delivered. That shift did not eliminate discrimination, but it weakened one of its most efficient conduits. When presence stopped being mandatory, many women, especially those with young children, experienced what amounted to a quiet wage increase. Roles that had previously required elaborate logistical coordination suddenly became viable.

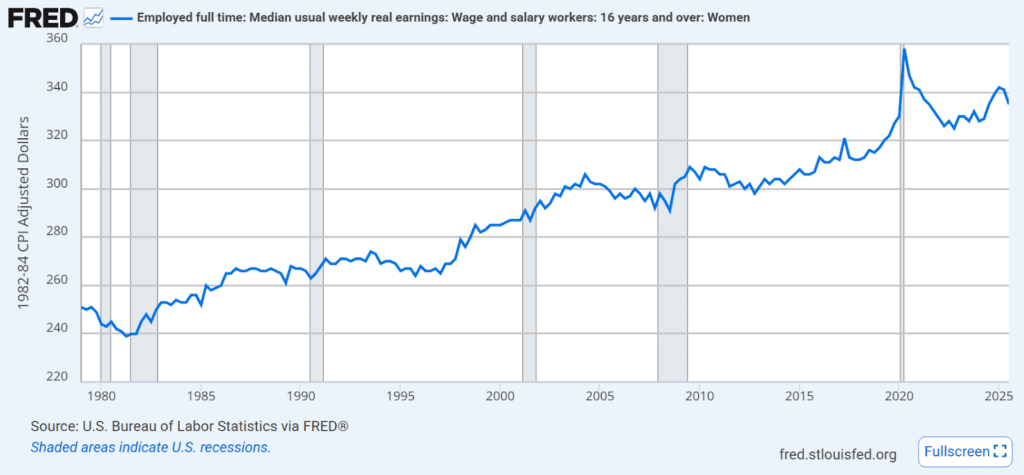

That repricing is now being reversed, which is already visible in earnings data. Real weekly earnings for employed women aged 16 and over have flattened, and in some periods declined, even as aggregate employment has remained resilient. As firms intensify return-to-office mandates, the gender pay gap in the United States has begun to widen again. Women working full-time earned about 81 cents for every dollar earned by men in 2023 — the widest gap since 2016 — and recent earnings growth has tilted decisively toward men.

This has prompted a natural question at The Wall Street Journal: Is the return to the office partly to blame?

When presence becomes a premium

The emerging answer is subtler than a simple indictment of offices. The issue is not location, but pricing. Physical presence has been repriced — and the burden of that repricing is falling unevenly. The contemporary gender pay gap is less about exclusion from work than about the terms on which work is offered: who must be where, when and at what cost.

Although these effects appear most clearly in gender-disaggregated data, the underlying mechanism is broader. Return-to-office mandates reprice caregiving and presence constraints that were previously absorbed by families and communities, with gender serving as the primary incidence channel rather than the root cause.

Strikingly, these dynamics fit squarely within an incidence — the party that ultimately bears the cost of a formally neutral rule once behavioral adjustment occurs — and institutional-design framework rather than an ideological one. Formally neutral workplace rules determine outcomes not by intent, but by who bears their economic burden. In this case, return-to-office mandates interact with pre-existing care constraints, revealing a broader institutional failure: the systematic mispricing of flexibility and caregiving time.

Firm-level decisions about presence impose external costs that are not internalized — slower human-capital accumulation, reduced matching efficiency and long-run fiscal drag — while the benefits of coordination remain privately captured. Framed this way, the argument is not anti-market, but pro-market. When care and flexibility are mispriced, productivity falls, the tax base erodes and valuable human capital is wasted.

Family and community structures historically mitigated these constraints by expanding the feasible set of work–family arrangements. Extended households, shared childcare and geographically rooted communities reduced coordination costs and allowed both parents to remain economically engaged. As these structures weakened through suburbanization, geographic mobility and career-driven sorting, the obligation to care did not disappear, but the infrastructure that made care compatible with economic freedom did.

As a result, caregiving now operates as a long-duration constraint on labor-market matching. Its costs are not always monetary; they appear as lost mobility, reduced risk-taking and diminished role reversibility — economic losses that remain largely invisible in conventional productivity or GDP metrics.

Japan provides a particularly clear illustration of this mechanism. While norms of family responsibility remain strong, three-generation households have largely dissolved — not because obligations disappeared, but because colocation did. As a result, both childcare and elder care now operate as long-duration constraints on labor-market participation and mobility. Importantly, the growing reliance on adult children for parental care has shifted substantial burdens across generations and cannot be regarded as a positive or sustainable solution. Nor does a simple return to three-generation coresidence constitute an unambiguous remedy: Such arrangements often entail significant psychological and emotional costs, including stress, role conflict and reduced autonomy, which themselves affect well-being and labor-market behavior.

Surveys of adults in multigenerational living situations by Pew Research Center and ImPossible Psych Services find that a substantial share report stress as part of their daily experience, rather than only benefit, underscoring that shared households can impose emotional and boundary challenges even as they provide care support. Psychosocial research on work–family conflict further shows that overlapping caregiving and work roles generate measurable stress and role conflict, which affect well-being and behavior.

Therefore, the economic cost of these arrangements is not limited to direct expenditures. Rather, it appears as reduced geographic mobility, narrower job matching, slower career progression and lower risk-taking over the life cycle. These constraints disproportionately affect prime-age workers precisely when returns to experience are most convex, helping to explain the coexistence of high human capital and persistent gender- and age-based labor-market segmentation. In this sense, Japan highlights how the breakdown of informal care infrastructure transforms family responsibility into an economically binding constraint, even in the absence of explicit discrimination.

A repricing, not a retreat

Standard labor statistics can obscure what firm-level evidence increasingly reveals. Women are not leaving the workforce en masse. Instead, constraints are forcing a reallocation within it — first across roles and hours, and increasingly across participation margins. Faced with the withdrawal of hybrid options, women, particularly mothers, are more likely than men to switch jobs, decline promotions or accept lower-paying roles that preserve some control over time.

Flexibility has become a priced attribute. Those who need it most are paying through slower wage growth.

This distinction matters. A worker who is willing to forgo approximately 5–10% of wages in exchange for remote work has not exited the labor market; she has been repriced within it through a compensating differential for flexibility.

The adjustment appears first in flows — job switching, promotion take-up, occupational sorting — and only later in stocks such as annual earnings. By the time the pay gap becomes visible in aggregate data, the underlying decisions are already sunk.

In economic terms, this is an incidence problem. Although the rule is formally neutral, its economic burden falls on those with the least flexibility to adjust, so identical requirements can produce systematically unequal outcomes. A rule that appears neutral — be in the office — functions like a tax whose burden depends on constraints outside the workplace. Where childcare is scarce, commutes are long and household norms allocate care disproportionately to women, the tax falls asymmetrically.

Why presence bites harder now

Two structural features of today’s labor market amplify these effects.

First, the cost of care has risen faster than wages across advanced economies, while supply has failed to keep pace with demand. These constraints bind most tightly during early-career years, when earnings trajectories are most sensitive to interruptions.

In effect, parents of young children face an effective inflation rate well above headline consumer price index — which measures overall price changes across consumer goods and services, including volatile items such as food and energy. This is because childcare costs have risen far faster than general inflation and absorb a large share of household income.

When firms require physical presence, households with young children face a sharply asymmetric choice set: Someone must absorb the added coordination costs. Empirically and traditionally, that burden falls more heavily on women.

This is not a story about preferences or “opting out.” It is a constraint story. Presence requirements function like a regressive tax — a tax that creates a larger burden on lower-income taxpayers compared to middle- or higher-income ones — on households with young children. They are highest when income elasticity is greatest. The tax does not appear on pay slips, but it is visible in behavior.

Second, pay growth in high-skill occupations is convex. Returns accelerate with seniority, responsibility and access to leadership tracks. When advancement requires continuous visibility while flexibility is confined to junior roles, small differences in availability today translate into large earnings gaps tomorrow.

Remote and hybrid work briefly severed this link. Coordination was decoupled from location, allowing workers to remain fully engaged without bearing the full time and care costs of presence.

Rolling back flexibility restores the old mapping — and with it, the old penalties.

From micro trade-offs to macro drag

It is tempting to frame these outcomes as individual choices. That framing is misleading. When experienced workers accept lower pay for flexibility, firms lose output, governments lose tax revenue and households lose lifetime income. Aggregated across sectors, the effect becomes macroeconomic — particularly in aging economies already facing labor shortages.

Historically, families and communities absorbed many of the coordination costs associated with work and care through extended households, geographic stability and shared informal support. As these structures weakened, the obligation to care did not disappear, but the institutional mechanisms that made care compatible with full labor-market participation did.

The repricing of presence therefore reallocates costs that were once social and intergenerational onto individual households. These costs surface first as wage penalties and career slowdowns, but ultimately appear as lower fertility, weaker community attachment and reduced long-run labor supply. Gender differences reflect where these costs land, not why they arise.

Global benchmarks help clarify the pattern. Across high-income countries, gender gaps in education and health are near parity, while gaps in economic participation and earnings persist. The problem is not human capital, but institutional conversion: how effectively economies translate capability into opportunity.

The return-to-office episode illustrates how quickly that conversion can deteriorate when flexibility is treated as a discretionary perk rather than as economic infrastructure. Where childcare systems, parental leave and bargaining institutions anchor flexibility, its pricing is stable. Where they do not, firms can reprice it unilaterally — and abruptly.

Measuring the wrong margin

Participation and educational attainment are measured meticulously. Schedule control, commute penalties and the wage cost of flexibility are not. As a result, inequality migrates to margins that conventional indicators underweight.

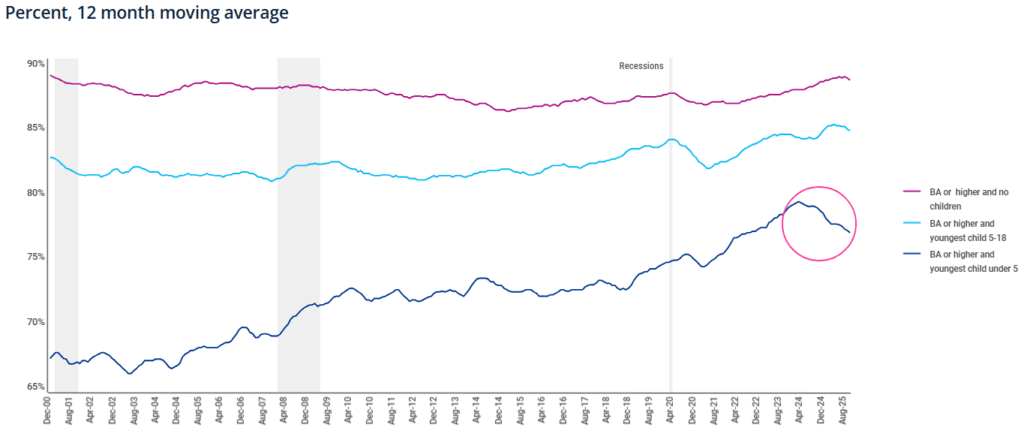

The graph below sharpens the diagnosis. Among prime-age women with a college degree, labor-force participation has risen since late 2023 for those without children and for those whose youngest child is school-aged. Only one group shows a sustained decline: women whose youngest child is under five. This divergence rules out broad demand shocks or white-collar layoffs as the primary driver. Instead, it points to a binding constraint that operates precisely where return-to-office mandates and childcare costs interact. Presence is repricing participation at the margin where care is least substitutable.

The COVID-19 pandemic did not create a new labor market. It revealed that physical presence had long been mispriced, and briefly demonstrated that this price was institutionally chosen, not technologically fixed. The return to the office is therefore not simply a return to normalcy; it is a return to a clearing mechanism that preserves participation while gradually eroding parity.

The central question is whether modern labor markets price time, care and presence in a way that allows families, productivity and equality to coexist. When those inputs are mispriced, formally neutral rules can sustain employment while systematically reallocating costs onto households and caregivers.

Presence itself is not the villain. The problem is pricing it poorly. In a high-skill, high-coordination economy, how work is organized matters as much as who works. Getting the price of presence right is no longer a marginal workplace preference — it is central to productivity, equity and long-run economic growth.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment