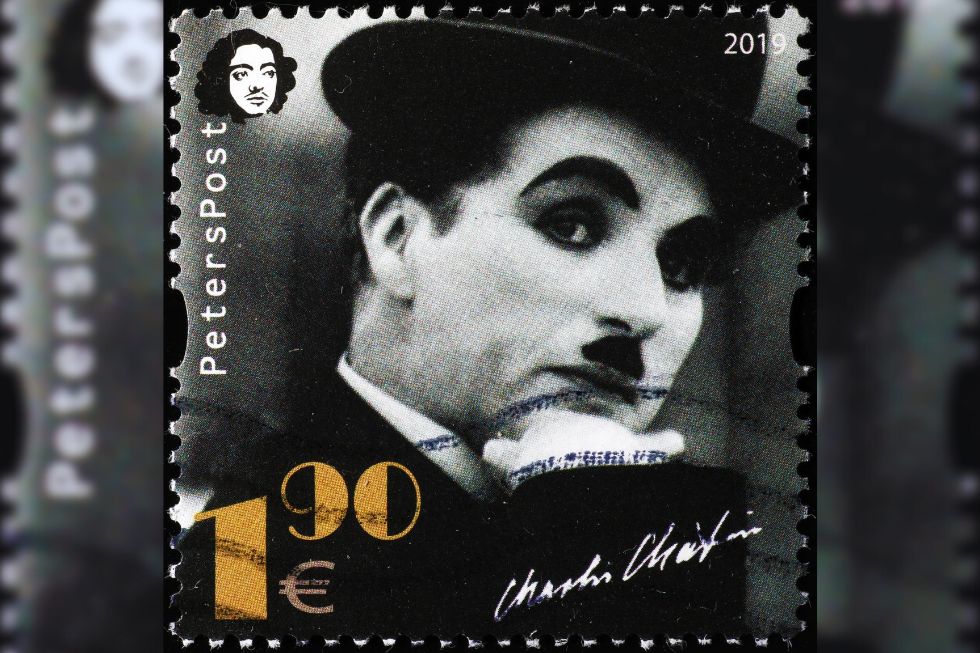

Every year, as December unfurls its lights and garlands down the streets, our subconscious first goes to the warmth of Christmas. Still, December 25 carries another resonance, more subtle, but just as powerful — it is the date on which English comic actor Charlie Chaplin died in 1977, at his Manoir de Ban in Corsier-sur-Vevey, on the quiet shores of the canton of Vaud in Switzerland. There is, momentarily, something singularly symbolic about this conjunction — Chaplin, who time and time again stood in for humanity, laughed at but hung tough, left us on the day that celebrates hope.

Living in Switzerland, I recently visited Chaplin’s World, the museum dedicated to his life and work, which is housed in the very mansion where he spent his final years. Wandering through light-filled rooms, observing every personal thing — photographs, film props and handwritten notes — I felt how alive the man remained behind the legend. There is nothing static about this place — each room tells a story of Chaplin, not as an untouchable icon, but rather as a passionate, sometimes tormented and very often ahead-of-his-time creator.

But what most impressed me was the coherence of his career. He was born poor in London, a music-hall actor prior to becoming an actor, director, composer and screenwriter. Chaplin was never just a figure of silent film — he was its most resourceful artisan, its most exacting poet. He invented not only a character but a universal language, understood by all. A language made of gestures and silences, capable of expressing social injustice, tenderness and the absurdity of the world, without a word being spoken.

The shadow of politics and the accusations of communism

Yet, the man who made the crowds laugh was also the target of suspicion and fierce political campaigns. In paranoid America in the 1940s and ‘50s, dominated by the specter of communism, Chaplin became a scapegoat. His politically engaged films — most notably Modern Times and The Great Dictator — irritated a certain conservative circle. An unwavering defender of the poor, denouncer of totalitarian regimes, his critique of industrial exploitation was enough to label him, in the spirit of the times, as a “left-wing sympathizer.”

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), under Director Edgar Hoover, opened a sprawling file on him, without ever proving any real adherence to communism. Congressional investigations followed, more for political suspicions and society gossip than for facts. The affair took a decisive turn in 1952. While traveling to London for the premiere of Limelight, American authorities revoked his re-entry permit. He, who had made America laugh for over three decades, was suddenly considered undesirable.

The blow was terrible, but Chaplin never let these accusations define him. Instead of an angry fight, he opted for silent dignity. He retired to Switzerland at the Manoir de Ban, where he lived with his family. There, surrounded by mountains and silence, he kept working-writing, composing and reflecting. Anyone who has visited the museum knows this strange feeling — one feels the exile, the peace, a life that is deliberately withdrawn but never extinguished.

A legacy greater than his films

What Chaplin leaves us today goes far beyond his films, brilliant as they may be. He bequeaths us proof that art can be popular without being simplistic, political without being partisan, universal without being abstract. Exploring his life at Chaplin’s World, I learned that his genius lay not only in his comedic talents but also in holding a mirror to humanity. The cracks of the world, yes, he knew, but also the beauty hidden therein.

The more Christmas draws near, while our societies are torn by injustice, exclusion and fear, Chaplin remains a beacon-profoundly discreet, profoundly tenacious. His laughter, tinged with melancholy, reminds us that it is always possible to combine humor and lucidity, poetry and commitment. He reminds us that one should never stop believing in human dignity — even when one is refused a visa, a place or the right to express oneself. Chaplin died on December 25, yet his work is born every day in those who still listen to him.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment