John F. Kennedy Jr. (JFK Jr.) was a symbol. A living heir to America’s most storied dynasty, the boy who saluted his father’s coffin on a rainy November day, the embodiment of lost promise and potential. From his first breath, born into a legacy both magnificent and merciless, JFK Jr. carried a mythology that did not ask for his permission.

His life — brief, luminous and tragic — became yet another chapter in the Kennedy family epic: a narrative of glamor and grief, triumph and ruin, that never seems to loosen its grip on the American imagination.

Now, three decades after the launch of George, the magazine he founded, and with a new TV series set to dramatize his relationship with Carolyn Bessette, the public gaze turns back to him; romantic, wistful and still insatiably curious. Such hunger is understandable. Myth, like art, consoles us. But it also simplifies and, in doing so, often obscures the more important truths.

There is something undeniably Shakespearean in Kennedy’s arc. A man born under the weight of history, haunted by an inheritance he neither sought nor could escape. He resisted the obvious path, veered away from politics, flirted with acting, practiced law and taught. And then, when he finally began to move toward the destiny everyone else had always imagined for him, the curtain fell.

Politics, reimagined

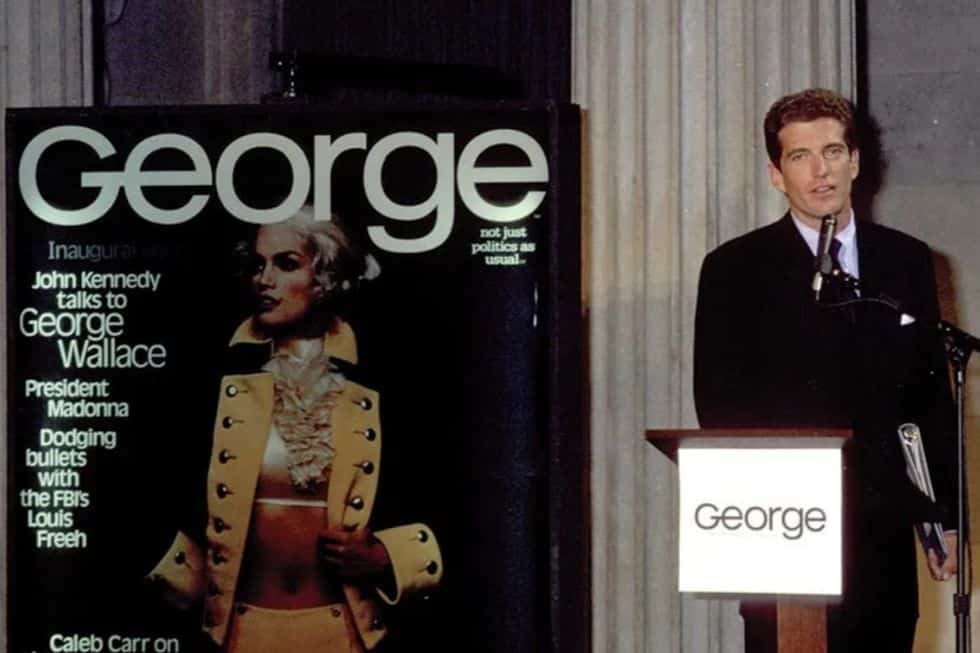

In 1995, John Kennedy Jr. did something fully unexpected. He launched a political magazine. But George was no ordinary publication. It wasn’t interested in dry policy briefs or op-eds for insiders. It was, instead, an audacious experiment in reimagining the political conversation entirely. He set out to do the unthinkable: merge politics with pop culture, to take two worlds long held apart and collide them with the energy of a tabloid and the earnestness of a civics class.

The first cover said it all — supermodel Cindy Crawford as George Washington, powdered wig and all. It was irreverent. It was provocative. It was brilliant.

The goal wasn’t just to humanize politicians, though it did that. The real ambition was to reinvent how people engaged with democracy; to invite the disengaged back into the conversation through a medium that didn’t talk down to them or shut them out.

Breaking the fourth wall of politics

Kennedy understood something that many of his critics — and many in power still — did not: that democracy cannot survive on solemnity alone. That in order for people to care, they have to be invited in. He wasn’t trying to dumb politics down. He was trying to pull it up. To meet people where they were, to make it feel vivid and relevant and, above all, human. In an era of sterile political coverage, George made politics feel alive again. Seductive, even.

Behind it all, there was something deeply personal. George wasn’t just a media venture but a personal dialogue with his past, with his legacy, with his ghosts. He filled its pages with stories that didn’t just cover politics but wrestled with the contradictions he’d inherited.

One cover featured Drew Barrymore styled as Marilyn Monroe — a silent, symbolic confrontation with an affair and a shadow that loomed large over the Kennedy name. He interviewed George Wallace, the segregationist who once stood in direct opposition to his father’s civil rights crusade. These weren’t editorial stunts. They were acts of reckoning.

What might have been

After Kennedy’s death, George couldn’t survive. And with it died not just a magazine, but the early promise of a new kind of political storytelling — one that treated voters not as passive consumers, but as participants. Its failure was existential. The culture wasn’t ready.

JFK Jr. represented the political figure who might have been: modern, sincere, unburdened by dogma. He stood at the edge of a new model of leadership, one grounded in charisma, clarity and care. And though he never reached elected office, he left something far more enduring than a title: the haunting awareness of what might have been. After all, sometimes, the most powerful legacies are the ones that never got the chance to disappoint us.

Presence beyond the last name

There’s a question Kennedy’s life forces us to ask: how can you belong to yourself when you seem to belong to everyone? In politics, that tension is constant. Public figures are expected to shoulder history, yet they are punished for not transcending it. Inheriting a legacy is treated both as a privilege and a disqualifier. Nepotism on one hand, myth-making on the other.

The only answer is authenticity. To be oneself, fully and without apology, is the most radical act in modern public life. Especially in an era where performance is mistaken for seriousness, and polish is mistaken for purpose. Kennedy was not interested in performative gravitas.

He understood something essential: that charisma is presence. It’s the invisible gravity in a room when someone walks in and makes people feel something — not fear, but connection. Possibility.

Everyone around him had an idea of who he should be; he was still trying to locate the person beneath their projections. That search lies at the core of human experience. And, in a way, it becomes political. Because politics, at its best, is not about power. It is about people. Their stories. Their contradictions. Their striving. Their hope. What we are brave enough to imagine and human enough to fight for.

[This piece was originally published in Greek in Athens Voice.]

[Casey Herrmann edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment