Decolonization appears to have become the new buzzword, the new currency circulating within academic circles, with several universities in the UK and the USA increasingly talking about decolonizing their respective fields of study, such as sociology, geography, cultural studies, criminology, etc. While not questioning the intent of such discussions and networks and rather standing in solidarity with the spirit to make university spaces and disciplines more inclusive both in content and pedagogy, this essay seeks to interrogate and deconstruct the decolonial turn within academic spaces as well as in popular political discourses, to express caution.

It is noteworthy that the term decolonization within academic institutions generally and for pedagogic reforms specifically is often employed interchangeably to mean inclusivity, diversity, pluralism and representation, and while we endorse all these ideas as central to any process of learning, we submit that the erroneous usage of the term, interchangeably with these ideas and tenets is neither correct nor necessary. Scholars like Jonathan Jansen point out that the debates within the decolonial paradigm had already been richly conceptualized in the anti-colonial struggle writings (Frantz Fanon in Algeria, for example) and in postcolonial literature studies (Ngugi wa Thiong’o in Kenya, as a more recent example). The use of the term decolonization only creates another problem: all problems in universities and the broader society are collapsed under the conceptual umbrella of decolonization.

Defining the decolonial: An exercise in ground-clearing

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò delineates how decolonization was understood as “making a colony into a self-governing entity, with its political and economic fortunes under its own direction. In the 1940s, decolonization literally meant the evacuation of soldiers and state officials and the end of formal colonial rule of one country over the other’. Others seem to agree while differentiating decolonization from decoloniality.

However, with the recent academic discourse on “decolonization” (including the political appropriation of the term), the term has come to acquire a more expansive meaning, ushering in what has been identified as the decolonial turn. This new turn aims to challenge the Eurocentric episteme in the production of knowledge and reconstruct the native system of knowledge in formerly colonized countries and regions. Thus, epistemic reconstitution seems to be the objective for decolonization, and this is a welcome step forward in the direction of critical traditions.

The discussions emanating first from the modernity/coloniality network, with Escobar and Mignolo as representative authors of this intellectual current, there is a conceptual base on which all proponents of the decolonial turn converge, notwithstanding internal heterogeneities, which is that “coloniality” is constitutive of modernity. In other words, the framework of decolonization bases itself upon the idea of a monolithically colonial modernity. For instance, Mignolo’s critique of modernity starts from the basic premises of the theory of coloniality of power as formulated by Quijano. According to this theory, the “colonial matrix of power” comprises every single area of human experience. Political authority and governance, the economy, sexuality and gender, the relations between human beings and nature, and culture and knowledge are the five domains that, for analytical purposes, decolonial theorists (with slight variations) often highlight. As Mignolo articulates, “coloniality is constitutive, not derivative, of modernity. That is to say, there is no modernity without coloniality; thus, the compound expression is modernity/decoloniality. In this understanding, the ex-colony is considered as being forever under the yoke of colonization, such that every cultural, political, intellectual and social endeavor, every idea, process, institution and practice that retains the slightest whiff of the colonial past is called into question. Sometimes, even the coterminous existence of a reality in the colonial era qualifies for being dismantled and annihilated. As a logical corollary, then, any form of decolonization will be considered complete only after all forms of domination, rooted in or coterminous with the colonial past, are overturned. Two moves in this regard are noted: first, postulating coloniality as the essence of modernity; second, repudiating every single tradition and concept assumed to be Western or modern as “colonial.’

This approach then accords a totalizing primacy to the history of colonialism such that the experience of being colonized surpasses all other developments in history. This includes the very exercise of self-governance in the independent post colony whose first moment of exercising decolonial control over its internal affairs, it must be emphasized, was by asserting sovereignty, an intrinsic part of which included conscious decision-making regarding what had to be retained and what foregone from the centuries that preceded the establishment of the postcolonial, independent state.

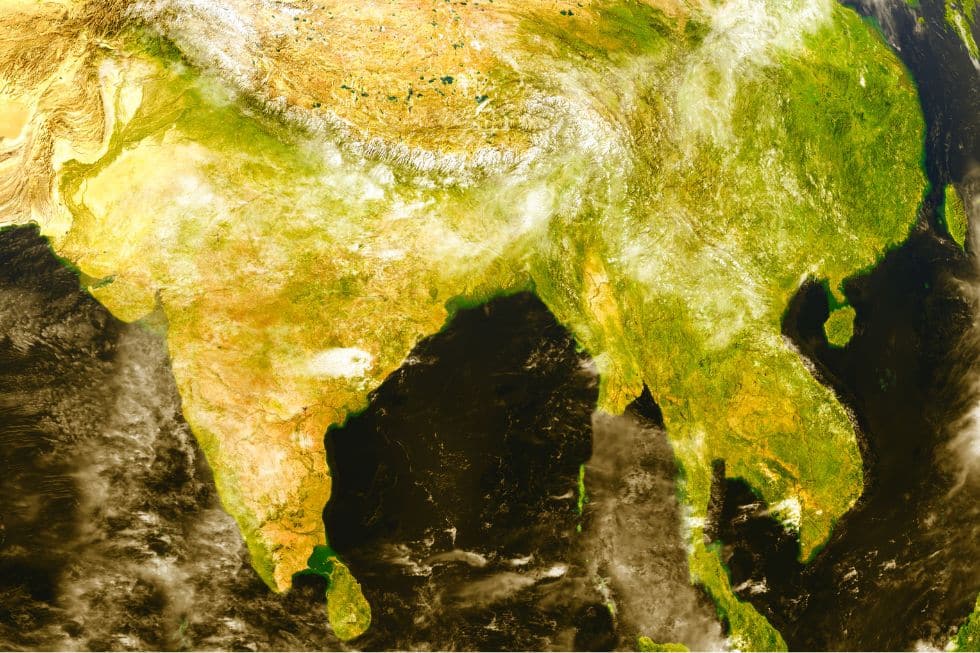

To decolonize, then, is to overcome that aspect of our colonial determination and “restore” or realize self-determination in the true sense. It is important to know what “the colonial” constitutes and conclusively state how the colonial past “determines” our present and in what ways. In doing this, it is often observed that the colonial is conflated with the modern, such that coloniality either corresponded with modernity or was itself the harbinger of modernity in the colonized states. Now, this is simply untrue for varied reasons. First, to go back to the idea of modernity on which this decolonial turn works itself out: the problem with this conception of modernity is that it ignores the tensions among multiple clashing political projects, traditions and social movements that have been an integral part of it, which have also left us emancipatory legacies that belong to the entire humankind and not only the “West” – and which were crucially forged through anti-colonial and other popular struggles, be it in Latin America or the Indian Subcontinent or elsewhere. Second, in contrast, colonialism, for the most part, and in most colonies where extraction formed the basis of the colonizer-colonized relationship, was inherently based on a denial of the principles and material conditions of modernity. There are several accounts of how British colonialism caused deindustrialization in India and led to a systematic flight of capital from the colonies. Rationality, self-governance, rule of law and capitalist modernization that form the tenets of colonial modernity were all deliberately denied to the colonies. Rather, the continued underdeveloped and culturally backward status of the colonized was integral to the sustenance and legitimacy of colonial rule, as it was based on the “rule of differenc.’. Modernity, then in many cases, supplied the anti-colonial struggles with a very effective ideological arsenal, and its language has been a lever for many emancipatory projects. Julián Harruch uses the case of Haitian revolution and independence revolutions in Spanish America to make this point, to which we can also safely add the case of Indian independence struggle.

The first question then is, has the decolonial scholarship furnished the criteria or yardstick based on which one may infer what qualifies as colonial and what does not? Or when does an object of enquiry assume enough content, in terms of determination, origin, causality, correlation, condition or influence linked to colonialism, to become a candidate for the decolonial paradigm? What are the markers to identify this? Further, we appreciate that the decolonial turn perhaps offers a correct diagnosis of why coloniality is deeply entrenched, arguing that its root cause of enduring strength lies in its inherent connection with modernity; but does that have to imply that the end of coloniality can only be attained through the end of modernity?

1. The promise of decolonization and methodological blunders

Next, decolonization is being used to talk about restorative justice through cultural, psychological and economic freedom, wherein colonization is seen more than mere territorial and political independence. Colonization, the story goes, continues culturally and psychologically by determining whose knowledge is privileged. Now if decolonization is about “an endless fracturing of the world colonialism created,” it is imperative for decolonial theory to rigorously reflect on what constitutes colonialism, the elements of its legacy, the factors and rationale for its continuing effects, but most importantly the normative positioning of the theoretical alternative ( that is, decolonial theory) towards each of these. The central contention we raise here is as follows: assuming that one accepts the continued influence and even existence of colonial forces manifested in institutions, practices and knowledge systems, are we to argue that despite a people or a nation choosing to retain traces of colonial residue in their legal or political systems or even socio-cultural practices, these should not be deemed as acts in sovereign self-governance?

Ming Dong Gu has pointed out, in the historical context of global colonialism, a conception of decoloniality that adequately reflects its real conditions cannot be divorced from the conditions of decolonization and its consequence – coloniality. Furthermore, historically speaking, was the force of colonialism so pervasive and totalizing, that no facet of the precolonial period could escape this absolutization? What explains the prevalence of pre-colonial and indigenous practices in parts of the world then, where colonialism was dominant? In other words, decolonial thinkers not only end up in errors on account of correlations and causality, but they also fail at the exercise of dis-entangling in terms of periodization and effect. Should we ossify the colonial logic, albeit in reverse, where North-South, West-Non-West are categories fixed in time, untenable to any change? Or to further extend the logic here, as an example, should we undo parliamentary democracy and related forms of polity and governance because the British colonial rule “exported” parliamentary democracy to the colonies and the colonies after independence chose to inherit it? What mode or form should decolonization entail here? What is further brushed away, is the tendency of decolonial thinkers to follow a linear trajectory of historical progression, despite professing otherwise, wherein the pre-colonial, colonial, post-colonial and decolonial can be neatly and impermeably separated, as if no socio-cultural exchanges could ever have taken place possibly. This denies the realities of human condition and social existence wherein history and culture constantly remain in active and diverse interaction in producing subjectivities, in the progress of knowledge and in reconstituting the normative foundations of social existence.

2. What is novel about the decolonial approach?

Further, if one is to ask what is novel about the decolonial paradigm or what is the intervention that it claims to make, there are no easy answers. While some scholars, in order to correct the limitations of decolonial theory, call for yet another return: return to the foundational aims of decolonial theory, which one of them states as: questioning unfair power structures for greater emancipation. The immediate point that must be considered is that there are several existing critical traditions that question the unfair power structures as their foundational aim and interrogate the colonial residuary forces that continue to inform the nature of the Indian state and the political or economic trajectory in the post-independent period. Postcolonialism is one, Subaltern studies another and Marxism has been there since long. To be more precise, it is particularly imperative for the decolonial approach to explain its contributions besides and interventions against the postcolonial approach. This is because the decolonial and postcolonial are adjunct approaches not only as anticolonial discourses but also because the “decolonial” has defined itself as a critique of the “postcolonial’. The authors of the work On Decoloniality, which some consider the most systematic account of decoloniality to date, have not merely vehemently denied but also regretted the conflation of decoloniality with postcolonialism. However, a lack of rigorous academic conversation between these (arguably) competing paradigms has led to several misconceptions regarding what they entail and to some extent has prevented decolonial theory from carving out a convincing niche for its intervention. To do justice to the significance of the decolonial as a response to the postcolonial paradigm, let us take a synoptic look at the criticisms levelled by the decolonial approaches against the postcolonial scholarship. They might be listed as follows. First, postcolonial scholarship while claiming globality is deeply embedded in anglophone legacy, the former British empire, thus falling prey to its own criticism of western literature. That is, the criticism goes, postcolonialism is essentially a “Eurocentric critique of Eurocentrism’. This criticism is levelled mainly through the geopolitical and historical blind spot in postcolonial literature which remains ambivalent on the position and significance of Latin America in the postcolonial discourse. In response, the decolonial approaches have been seen as expanding the historical and geographical scope of postcolonial literature. Postcolonialism’s inability to transcend Eurocentrism in “true” sense is also argued on the ground that the postcolonial approaches heavily deploy western canons, most importantly poststructuralist scholarship (such as works by Lacan, Foucault, Derrida). In response, decolonial approaches argue for “border thinking” through a delinking with the western canons. Lastly, the “post” in postcolonial scholarship is frowned upon by scholars of decoloniality as reflective of ambiguous political intentions. On each of these fronts, it must be argued, that decolonial scholarship has not necessarily clarified or put across a more rigorous theoretical alternative which renders decoloniality at best a progressive rhetoric. For instance, the very fact that the buzz of decolonization seems to have captured the university spaces in the UK and the USA says something about the motivations of scholars in speaking about decolonization in a predominantly white context that often does not truly echo the call for “border thinking’.

Furthermore, it is not really clear that in the academic conventions of knowledge contribution wherein new knowledge is considered credible when it engages with the existing canons of the discipline (even if it is to dismantle and call out the racial basis of such knowledge), how does “border thinking” facilitate academic discourse by existing besides and in isolation from the disciplinary canons which in most contexts would (unfortunately) be “Western” so to say. It is one thing to say that the knowledge paradigms of the non-west or erstwhile colonies be taken seriously, that the voices from the margins be recognized as legitimate knowledge production and another to say that these voices should stand on their own and alone. If the charge on western academia is of being an echo chamber, that cannot and should not be countered by another echo chamber albeit from a different geographical location. This runs counter to the very logic of how disciplines evolve, that is, through “critique’.

This is not just an analytical problem but also a normative one. Decolonial scholar, Aditya Nigam, argues that one of the reasons for the Hindutva appropriation of decolonization discourse in India is that the precolonial and the indigenous is dismissed by the “secular-modern,” thus ceding the ground to the Hindu right discourse that associates that past with Brahmanism and spiritualism, thereby, discouraging any productive discourse about the epistemic exclusions and “ontological depletion” caused by colonialism. While the point about ontological depletion is important, as postcolonial and anticolonial writings have highlighted, what remains contentious is whether the ontological “recovery” lies in turning towards the past. One must also ask whether critical traditions such as postcolonial and decolonial theories should not draw upon the critical canons of a given discipline (such as Marxist literature) either to build its claim or even to carve out its distinctiveness.

It may also be highlighted at this juncture, that even with respect to the Marxist tradition that forms a part of the ensemble of critical traditions interrogating colonization and the political economy of the postcolonial states, decolonial scholarship provides less to strengthen the theoretical form and substance of such a critical tradition but does err on the most obvious pitfall of the same. Marxist tradition has been criticized by all major traditions for its historical determination which in turn rests on a specific kind of structural determination. It is curious that such a charge has not been levelled against decolonial scholarship, the entire logic of which is based on the colonial (that is, historical) determination of the post-colonial (that is, the present). In Marxism, at least it is made intelligible why such a historical trajectory is charted out – as the tradition locates itself strongly within a material analysis, within political economy. Decolonial scholarship lacks fervour even on this front — it leaves us with historical determination of some sort, without any internal explanation for why the colonial history should necessarily impact its succeeding phase and the manner in which it does so. The theory lacks dismally on the front of explanation and seems to be more concerned with decolonization of knowing and knowledge than with the material means responsible for the colonial existence or with what brought about colonization in the first place. Furthermore, decolonial theorists portray Marxism as an essentially European form of thought, ill-fitted to the realities of the Global South. Some decolonial theorists go a step further and attribute the failure of many anticolonial movements in the mid-twentieth century to their leaders” misguided embrace of Marxism or socialism. If there is an exemplary exercise in reductionism and misreading – it is this. A cursory look at the works of scholars and thinkers like Aijaz Ahmad, Randhir Singh and Walter Rodney will be enough to rebut criticism of this kind.

Now, let us ask what does decolonization offer us in terms of an alternative vision of human existence or is there a theory of change on the offer for us: is it a return to the precolonial times? If yes, then the decolonial thinkers would need to present “evidence” to prove that the precolonial times are better suited to human emancipation and those times were one of human glory and splendor, as if recorded history of precolonial times is free from oppression, injustice and discrimination: caste system and sati system, among other systems of oppression, was not a product of colonialism even as the latter may be seen as transforming and in some instance aggravating the former! Is it a recovery of the indigenous ways of life, if so, then the question becomes: is each indigenous way of life by itself emancipatory? If yes, how, if no, then from where do we arrive at the parameters and standards to decide what qualifies as emancipatory indigenous practice, worthy of recovery and re-incorporation?

So now, if the decolonial scholarship is indeed at the very best a progressive rhetoric and is to be sympathized with as an ally in the anticolonial movement (considering its progressive political stance), then the political implications of such an approach gains an existential weight. That is, to fail politically would be to fail thoroughly. And it is in this light, that the recent right-wing appropriation of decolonial approaches gain paramount significance in evaluating the merits of decolonial theory and not just as an incidental misappropriation of a rigorous critical theory.

3. Interrogating the political canopy of decolonization: The case of India

Now we turn to the political appeals for decolonization, and the political canopy which it offers, particularly taking the example of India. In the Indian context, the call for decolonization, largely polemical, has given way to consequences visible in the right-wing appropriation of this discourse. This has taken many forms and directions: from name change or undoing of colonial buildings to repackaging of colonial laws, from changing the history syllabus in schools to vernacularization of schemes and policies, etc. The underlying idea serving their revivalist agenda is the cry for a “pure,” glorious, civilizational past, largely a Hindu India. One of the fallouts of a rather flimsy grounding and invocation of the “colonial” in decolonial scholarship spills over or becomes an easy shorthand for the right-wing discourse on decolonization as well, such that the right wing ostensibly constructs not just the British as colonizers, but the Mughals too. In fact, the sob story of colonization has now emerged as a dominant trope in constructing and maligning “the other” in opposition to which a purportedly true indigeneity and agency is claimed. This explains how the ruling regime in India could overhaul the criminal laws in the name of decolonization (owing to the institution of these laws during the colonial rule) while retaining the typical characteristic of a colonial state – wide-ranging, arbitrary power to the executive and dilution of safeguards for the citizens. Here is the problem: the view of history that the right-wing relies on to push its mission to decolonize, wherein this Indian history can be neatly divided into three distinct periods: ancient Hindu, medieval Muslim and the modern British – is in fact a view of history fermented by the British and therefore in many ways a colonial project. It is interesting how the Right seeks to push for decolonization based on the colonial understanding of history, uncritically.

Further, the Rightward shift in Indian politics was considered by many as the beginning of a real process of decolonization, simply because of the erroneous assumption that after the British left, India continued to be ruled by a tiny, westernized elite, under the leadership of Nehru, whose worldview and lifestyle were closer to the erstwhile colonial rulers than to those they ruled. In this light, then, how is one supposed to view the fact that independence was much more than the substitution of an elite for another; it involved a transformation of the constitutive rules of the political game, in this case through a constitution through which several marginalized sections could claim their rights and claim their stake in the country as citizens.

Drawing on the decolonial scholarship which argues that despite the end of colonialism, colonial structures of power have remained fundamentally unchanged and even strengthened in the past two centuries, this in a way implies that there is no qualitative difference between colonial India and postcolonial India, as this discourse conveniently conflates as well as separates the question of misgovernance by the postcolonial state and colonial governance as and when appropriate for political cum policy mileage and electoral mobilization. In other words, it is a dishonest cover-up of the missed opportunities vis-à-vis governance and all this, as it celebrates Independence Day and takes great pride in nationalist movements and the stalwarts leading the movement, some of them which it tries to appropriate also, while simultaneously dismissing the qualitative differences between the colonial and postcolonial India! One might ask – what is the celebration about, if the times then and now are essentially the same, let alone the point about risking anachronism! If one needs to learn how to have the cake and eat it too, perhaps this is the chance? Decolonization then denies the anti-colonial struggle and historical process that paved the way for self-governance, even if it implied a bad form of self-governance.

4. A theory on platter for the Right: Beyond the politics of appropriation

In India, therefore, a peculiar situation has arisen, wherein more than marginalized sections of the society, it is the Right wing that is aggressively pushing for decolonization in the popular discourse. It is here that the scholars of decolonization must pause and evaluate what it is that they have served on a platter to the forces of the right in India. The issue of what is alleged as “intellectual slavery,” which is more of a question in pedagogy, curriculum and institutions, than of slavery and colonial hangover, and needs to be buttressed further with more empathy than rhetoric. For instance, Anglo-American scholars’ enthusiastic projects of decolonization tend to lack any reference to scholars, activists, and thinkers from the “Majority World,” thereby continuing the “epistemological exploitation” and reproducing the colonial logic that denies agency and knowledge-producing capacities of the colonies. This is accompanied by, or rather is a symptom of a more fundamental weakness of the decolonial theory, which is, the ignorance of political economy and the substantive question of redistributional justice. This reaffirms the point made previously, that decolonial theory seems to negate all strengths of critical traditions, such as, here, Marxist tradition (namely, its rigorous material analysis), thereby subconsciously falling prey to its own proposition of disregarding “western canons” in search for “authenticity” — an exercise in analytical myopia and intellectual ignorance. Any proposals for inclusivity and diversity, which form the mainstay of the decolonial rhetoric in academic circles, need to be preceded by a commitment to the redistribution of global capital (which includes the knowledge capital). Anything less than that is but an exercise in obfuscation.

Further, what baffles the mind is how the Right packages its projects of homogenization, be it of a uniform curriculum, a language, a culture, a legal code in the name of decolonization, on a country which thrives on a diverse social fabric, while calling for a return to indigenous knowledge forms, which are equally diverse – this continues to escape all trails of logic! If anything, in the name of decolonizing, the Right in India could not be further from the exclusionary ideologies that drove colonialism to its extreme: Nazism and Fascism are a case in point.

Colonialism was not bad merely because it was a rule by a foreign power; it was bad because it withheld the fruits of modernity from the masses and unleashed a politics premised on exclusion based on race, religion and region: a ground which is also shared by the forces of the Right in India currently, all that in the name of decolonization. If decolonization had to be done right, the first target under question would be the existence of nation-states premised on borders and boundaries as a mode of organization, and the system of capitalist accumulation based on the exploitation of labour and nature, but no government of the day would risk this line of operation ever.

5. Conclusion

In essence, the decolonial paradigm finds itself trapped in a paradox. While purporting to offer a liberating framework for intellectual and societal transformation, its theoretical foundations remain shaky, prone to reductive causalities and ahistorical assumptions. Simultaneously, its political deployment has been co-opted by reactionary forces seeking to advance regressive, exclusionary agendas antithetical to the principles of emancipation and plurality.

The way forward demands a critical re-evaluation of the decolonial turn. Scholars must engage in rigorous self-reflection, addressing the conceptual and methodological limitations of their approaches. They must also confront the uncomfortable reality of how their rhetoric has been appropriated by forces that undermine the very essence of decolonization. Ultimately, the quest for true decolonization necessitates a nuanced understanding of history, a willingness to embrace complexity and a commitment to fostering inclusive, pluralistic societies. Failure to do so risks rendering decolonization a hollow buzzword, devoid of its transformative potential and susceptible to co-optation by the very forces it claims to resist.

[Economic and Political Weekly accepted an academically expanded version of this article for publication in its Perspectives section.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Commenting Guidelines

Please read our commenting guidelines before commenting.

1. Be Respectful: Please be polite to the author. Avoid hostility. The whole point of Fair Observer is openness to different perspectives from perspectives from around the world.

2. Comment Thoughtfully: Please be relevant and constructive. We do not allow personal attacks, disinformation or trolling. We will remove hate speech or incitement.

3. Contribute Usefully: Add something of value — a point of view, an argument, a personal experience or a relevant link if you are citing statistics and key facts.

Please agree to the guidelines before proceeding.