In a global competition between governing philosophies, democracies seem to have lost both the narrative and the reflexes to fight. Two decades of increasingly urgent warnings from political scientists should have triggered a broad strategic reckoning; instead, the erosion of democracy is often treated as a domestic pathology rather than a global struggle reshaping the international order. In an age of renewed ideological rivalry, only one side appears to recognize that a contest is underway.

It wasn’t so in the last bipolar era. American historian Gary Gerstle argues that the Cold War’s ideological pressure forged a rare political consensus in the US: that governments had a mandate to raise living standards and fulfill the promises of the New Deal. This theory explains why President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, presided over incredibly progressive taxation policies. Gerstle explains that Eisenhower knew the Cold War had two fronts — one military and one ideological — and that at the heart of the ideological battle lay the question of who could provide a better life for their citizens. This defensive posture, and the civic architecture which supported it, collapsed along with the USSR in the 90s. Today, as democracies confront aggressive interference from authoritarian regimes, the response begins and ends with an all-too-familiar statement of concern.

The nature of the threat

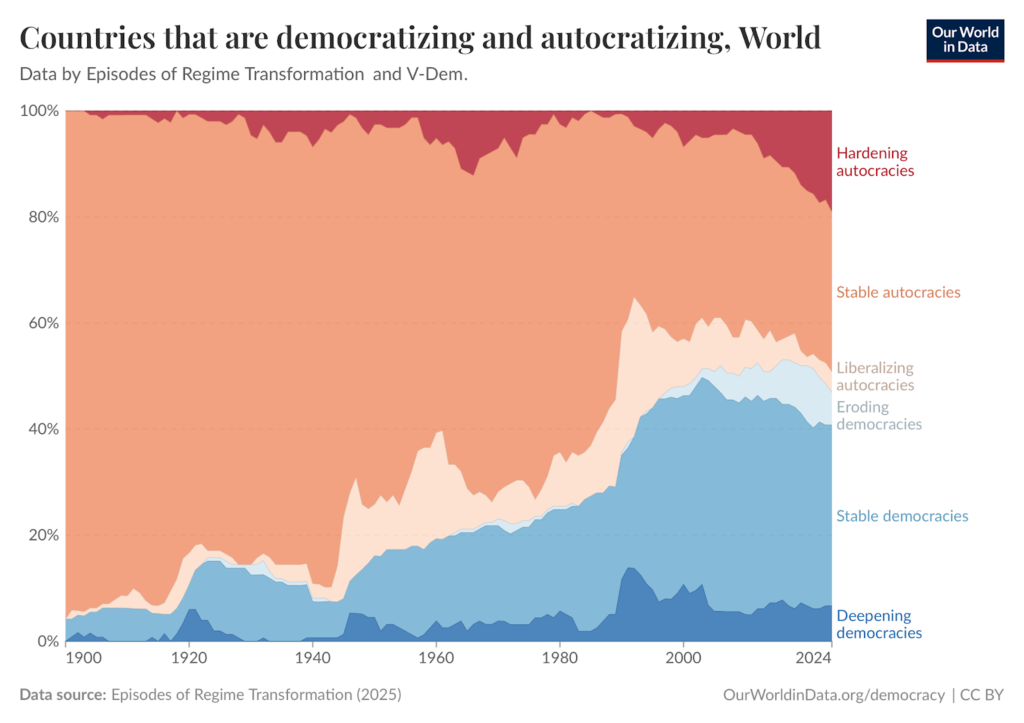

While democracies have historically demonstrated superior results for their citizens, every major democracy-tracking index shows marked and longstanding democratic decline. Some scholars attribute this decline to opportunistic actors who exploit democratic systems for personal gain, arguing that “[b]acksliding is less a result of democracies failing to deliver than of democracies failing to constrain the predatory political ambitions and methods of certain elected leaders.”

Others claim that the erosion of democracy is overstated, or even illusory. Revisionist scholars argue that claims of global backsliding reflect coding bias, not reality. It’s true that when the data is aggregated and viewed over a century, it is actually autocracies that have lost the greatest market share.

A more nuanced and accurate understanding would be that the threats facing democracy have evolved, becoming harder to quantify: “open-ended coups d’état, executive coups, and blatant election-day vote fraud are declining while promissory coups, executive aggrandizement and strategic electoral manipulation and harassment are increasing.” This creates a dual challenge: these subtler forms of backsliding are harder to mobilize against because they appear technical or subjective, and they are often legitimized by democratic institutions, leaving few democratic mechanisms of recourse.

Changing democratic views

The mainstream debate around democratic backsliding often fails to consider both the data on the actual state of democracy and the data on public opinions of democracy. This is where the outlook worsens considerably. Democratically elected leaders with authoritarian tendencies are, after all, chosen by discontented democratic publics. Politicians may be transient, but the deeper social forces eroding trust in democratic institutions are more enduring, and far more difficult to reverse.

Across multiple domains, research points to a toxic interplay of internal and external forces that are weakening democracies from within while amplifying tensions between them. One indicator of this erosion is the Edelman Trust Barometer, which measures trust in four key institutional pillars — government, business, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the media. Strikingly, business now ranks as the most trusted institution, surpassing NGOs, the media and especially government. It is also the only institution rated as both competent and ethical, while government ranks lowest on both dimensions, followed closely by the media (a well-known vulnerability in democracies, exploited by autocratic states through influence operations).

This collapse in confidence is not recent; trust in political institutions across advanced democracies has been on a steady downward trajectory since the 1960s. Today, only 22% of Americans trust the Government, compared to 77% in 1964.

One grim but plausible interpretation of this long decline in trust is that democracy may have a kind of political “shelf life” — a point after which public sentiment turns against the entire governing class, with no major actors viewed as capable agents of meaningful change. This dynamic leaves democracies increasingly vulnerable to nonkinetic interference by foreign adversaries, a risk underscored by troubling polling of Western youth that reflects a waning faith in democracy as a governing ideology.

The youth crisis

Youth are prime targets for foreign information operations because their political views will determine the future viability of democratic systems, yet their attitudes are still forming. Having, with few exceptions, no lived experience of authoritarianism, they tend to evaluate democracy through outcomes (e.g., housing, jobs, climate policy), which makes them particularly receptive to narratives that frame governance models as interchangeable. They are immersed in polarizing, algorithmically-determined information environments that privilege emotion, identity and grievance over deliberation or compromise.

At the same time, they are disproportionately exposed to the policy failures of mature democracies — housing scarcity, labor market issues, climate crisis and declining socioeconomic mobility — providing fertile ground for narratives that recast real grievances as evidence of democratic exhaustion. Weaker adherence to norms and greater openness to disruptive forms of political action further reduce the social and psychological barriers to democratic youth disengagement. From a foreign adversary’s perspective, information operations targeting youth are a low-cost, long-horizon investment. It is not necessary to persuade them to embrace authoritarianism, only to stop believing that democracy can solve their problems.

Surveys consistently show that younger generations are increasingly disengaged from democratic norms. According to one study, less than two-thirds of young Americans exhibit even a “passive appreciation” for democracy, while roughly one-third express “dismissive detachment.” The authors concluded that, overall, Americans appreciated democracy in principle but not in practice. Similarly, in Europe, a July 2025 poll found that 39% of young Europeans believe the EU is not particularly democratic, nearly half do not understand how EU institutions work and over half think the EU is a good idea that is poorly implemented.

In the UK, the picture is more alarming still. One poll found that 52% of Gen Z in the United Kingdom believe their country “would be a better place if a strong leader were in charge who does not have to bother with parliament and elections,” and 33% agreed that “the UK would be a better place if the army were in charge.” Reducing the possibility that this was an anomalous or erroneous result, another poll found that 27% of youth in the UK would rather live in a dictatorship than a democracy, while only 57% declared a preference for democracy over dictatorship. (Interestingly, the authors of that poll were just happy to see democracy supported at rates over 50%, and warned against “catastrophizing.”)

This tracks with global trends of youth radicalization. Across the countries surveyed in the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, a majority of young adults (18–34) now express support for at least one form of “hostile activism” to drive political change, including the intentional spread of disinformation or the threat or use of violence. Youth support for political violence is rising worldwide, and there is no ready-made policy solution to combat this trend.

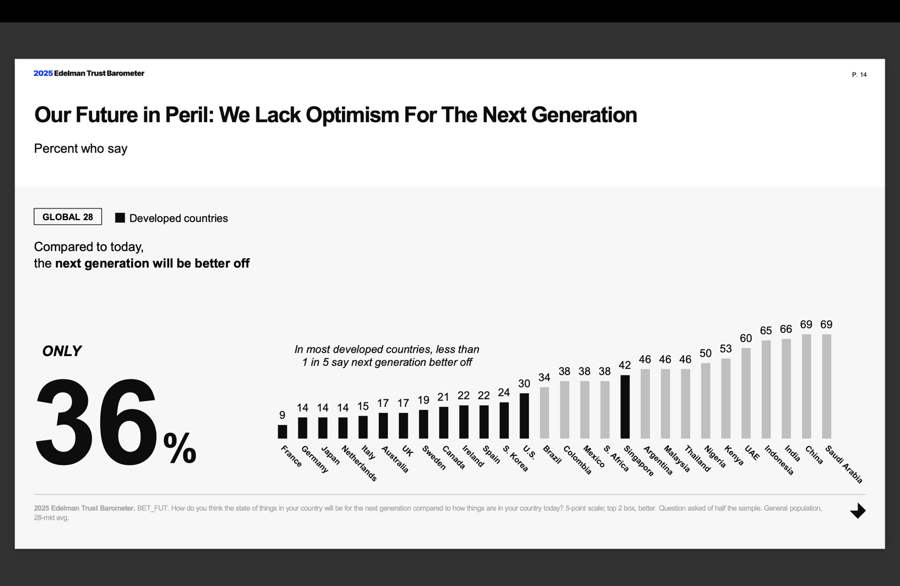

The Trust Barometer also offers a possible explanation for why the “kids aren’t alright” — a collapse in optimism. Democratic and developed societies no longer believe that the next generation will be better off. This sentiment appears irrespective of geography, but correlates strongly with governing ideology. The most pessimistic countries include democracies like France (9% affirmative response) and Japan (14%), while China and Saudi Arabia were tied for most optimistic, with 69% answering affirmatively.

The authoritarian angle

These are just some of the pressures affecting democracies — but are autocratic states faring better? Polls only show a moderate rise in international perception of the principal authoritarian countermodel, China, while US favorability has cratered, meaning Beijing improved in standing primarily by comparison. China will likely continue to be held back in international esteem by its multitude of government abuses, but domestically, the picture is harder to measure.

Chinese trust in government is consistently reported at exceptionally high levels, sometimes even above 90%. As with all social science results from a tightly controlled authoritarian society, data from China should be viewed cautiously. At least one study has shown that these high ratings may be vastly inflated by methodological issues and fear of retribution. At the same time, China has become known for its comprehensive information operations, which aim to promote the legitimacy of its political model. While these have sometimes faltered abroad, they dominate the domestic information sphere, where they have very little narrative competition.

But authoritarian rule makes it harder to shift the blame for policy errors, and Beijing is unlikely to undo the damage from its most serious mistakes anytime soon. After wiping out over a trillion dollars in market value through tech-sector crackdowns, the Chinese government unintentionally engineered a historic property-sector crash and bungled the cleanup, offering a steady stream of centralized planning failures.

An even more intractable problem is the legacy of China’s draconian population-control policies, which have left the country with a rapidly aging society, a shrinking workforce and skewed gender ratios. Adding to this list of “grey rhinos” — high-impact risks that are plainly visible yet persistently unaddressed — is the mounting local-government debt crisis, a stark illustration of China’s underlying fiscal fragility.

It’s starting to show. The Chinese government contends with growing protests and other signs of widespread public discontent, often related to economic issues. Its cat-and-mouse game with dissidents has reached surreal levels, both online and in real life, indicating deep regime paranoia. Optimism that the next generation will be better off dropped by 13 percentage points in the past year. However, it’s unlikely that these domestic issues place any meaningful check on the ability of China and its authoritarian allies to conduct successful information operations undermining Western democratic sentiment; in fact, the worst possible interpretation of China’s internal issues would be to discount it as a foreign threat.

The legitimacy gap

Still, the central question remains: if no alternative model has historically delivered better outcomes for human welfare, why is democracy losing in the court of public opinion? Part of the answer lies in the diminishing returns of maturity. In rising powers, citizens experience rapid, visible improvements, but in advanced democracies, progress is typically incremental and appears stagnant in comparison. Economic woes are now at the top of voter concerns in democracies, illustrating how past democratic gains have been eclipsed by the rising costs of housing, education and healthcare.

At the same time, autocracies are learning the skill of performative reform, tightly managing narratives to align with social norms and working to obscure their failures, while liberal democracies continue to air every flaw in public. Autocrats have remembered the failures of the Soviet glasnost, but populations in established democracies have forgotten the deprivations of life under dictatorship.

Compounding both dynamics is a polluted and contentious information environment. Here, democracies are under attack at the point of their most severe disadvantage: openness and tolerance of dissenting viewpoints are both key democratic characteristics and a boon to those who strategically promote disinformation. The result is a growing legitimacy gap: even as democracies continue to offer a better system overall, fewer and fewer citizens believe the system works.

The international impact

Global confidence in US leadership is falling fast, most dramatically among core allies. In April 2025, Ipsos polling showed the United States’ global influence dropping below China’s for the first time, with China continuing to gain ground. This declining trust in US leadership is weakening alliance cohesion, disrupting economic coordination and creating more space for authoritarian influence internationally. Allied publics are especially susceptible to exploitation; adversaries seeking to fracture alliances will find it far easier to amplify well-founded doubts about US reliability.

The same policy shifts are also making Western allies more likely to implement a competitive industrial agenda against one another, even if it means forgoing collective gains. In an example of the prisoner’s dilemma, a lack of trust amongst allies may result in the bloc as a whole failing to achieve what it might have. If allies no longer believe the United States is reliable, they will hedge — including, as Canada recently demonstrated, by diversifying toward Chinese systems and markets despite the risks involved. This is particularly concerning in strategic sectors where China is making extraordinary advances, such as shipbuilding, aeronautics and missiles, putting its defense exports in a stronger market position. Lower alliance trust also raises the cost of coalition-building, undermines sanctions alignment, and complicates nuclear and deterrence planning.

The West’s soft power rests primarily on the belief that democracies can solve social and economic problems better than any rival system and deliver clear benefits for the populace. As confidence in that promise erodes, authoritarian states do not need to outcompete so much as fill the void. In this legitimacy vacuum, autocracies gain strength by default.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment

A sharp and timely analysis. The framing of legitimacy as a battle over perception rather than mere institutional performance is particularly compelling. The generational dimension adds real depth to the argument. An important contribution to the democracy debate. My compliments to Emma Isabella Sage.