US President Donald Trump has done something no adversary of the United States ever managed: he has pitted the Atlantic alliance against itself. What was once assumed — a permanent American commitment to Europe’s security and to a liberal order it largely designed — is now openly in doubt. At Davos this week, Trump delivered a characteristically erratic speech that careened from topic to topic, insulting his hosts, threatening European economies and leaving allies with the impression that the United States is no longer a predictable partner but a volatile actor that might turn on them at any time. The spectacle underlined a disturbing reality: the sheriff no longer enforces the law, except his own.

The core of the Western Alliance since 1949, Europeans and Canadians find themselves faced with a new harsh reality, sandwiched between two hostile or unreliable powers, Russia and the United States. In such a scenario, a passive Europe might degenerate into a mosaic of fiefdoms: some under Russian influence, some under American pressure, some drifting toward China. Canada has already begun to rebalance in that direction. Faced with that prospect, Europeans — and especially Germans — will reluctantly choose rearmament. They will become “normal” powers again.

How would Germany, specifically, behave if the Atlantic alliance erodes or collapses under the strain of Trumpist nationalism and willful unpredictability in Washington? How would Berlin recalibrate its alliances and buffers, its place inside — and eventually beyond — the European Union? To answer that, we have to go back to the last time Germany confronted an unpoliced, anarchic system of great-power rivalry: the decades before the First World War.

A historical pattern emerges

Historians of Germany will recognize a pattern in what we are witnessing today. For three decades after German unification in 1871, Otto von Bismarck played the role of an unsentimental manager of order: a ruthless tactician in war, but once his aims were achieved, a conservative balancer who tried to prevent the system from blowing up. His successor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, was the opposite — impulsive, vain, narcissistic and prone to grand, erratic pronouncements that frightened friends and emboldened rivals. He wanted every day to be his birthday, one wag quipped.

Today, the contrast between the relatively steady — some would say too weak, but in any case — order-preserving foreign policy of the Obama and Biden administrations and the unpredictability of Trump’s rhetoric and statecraft looks eerily like that earlier shift: from Bismarck to Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Bismarck, the Prussian statesman who created the first unified German nation-state in the 1860s and 1870s, offers a blueprint for how a rising power behaves when it feels insecure — and what it does once it has secured itself. Between 1864 and 1871, he engineered three short, brutal wars: against Denmark to seize Schleswig-Holstein; against Austria to push it out of German politics; and against France to complete unification and proclaim the German Empire at Versailles. These wars were not mindless aggression but calculated moves to solve what Bismarck saw as Germany’s structural vulnerability: a fragmented nation in the middle of Europe, surrounded by stronger imperial powers.

After 1871, Bismarck declared that the new Germany was a “satiated” power. Having achieved unification and key territorial gains, he pivoted from conquest to preservation. His greatest fear now was encirclement: a coalition of hostile powers aligning against Germany. He responded with an elaborate web of alliances and treaties to freeze the system in place. In the 1860s, he used force to create a power; in the 1880s, diplomacy to preserve it. The lesson is clear: rising powers fight to secure their position; if they are prudent, they then try to declare the game over. But the game never ends.

When Bismarck falls, someone else sits in his chair.

Wilhelm’s gambit

When Wilhelm dismissed Bismarck in 1890, the logic of German foreign policy shifted. The Reinsurance Treaty with Russia lapsed. Naval competition with Britain became an obsession. Colonial adventures, Balkan crises and the Wilhelm’s own erratic public outbursts replaced Bismarck’s cold calculation.

Wilhelm’s bombastic and often irrational statements — the famous Daily Telegraph interview and the two Morocco Crises were only the two best-known examples — alarmed allies and adversaries alike and convinced many that Germany was unpredictable and dangerous. Historians now see Wilhelm’s mixture of insecurity, vanity and impulsive rhetoric as a major factor in the chain of miscalculations that led to 1914.

The result was not a master plan for world domination, but something more banal and more dangerous: anarchy unmanaged. Arms races accelerated, alliance commitments hardened and each crisis was “resolved” in ways that preserved the appearance of peace but eroded trust. When the heir to the Austrian throne was assassinated in Sarajevo, there was no trusted arbiter, no accepted enforcer of rules. The dominoes fell in the dark.

This is what international relations theorists mean by anarchy. Kenneth Waltz, in his book Theory of International Politics, does not use the term “anarchy” for chaos but for the structural fact that there is no world government, no global police. States exist in a self-help system. Hedley Bull, in The Anarchical Society, made the same point more gently: there is an international society of states, but no sovereign above them. Without a superordinate authority, states must balance, arm and pre-empt to survive. Miscalculation is built into the environment.

Germany’s insecurity in such a world was not imaginary; it was the central fact of the European order. Once Berlin believed that Russia was mobilizing and that France would join, Bismarck’s nightmare — a two-front war against an encircling coalition — moved from theory to calendar. War became thinkable, and therefore likely.

From a purely foreign policy perspective, Hitler’s incorporation of German-speaking territory into the Third Reich up until 1938 looked Bismarckian. Had he stopped there and announced that Germany was satisfied in terms of any further demands, he would possibly have gone down in history as a second Bismarck, this time establishing a Pan-Germanic state, rather than a smaller Germany under Prussian domination. But his fanatical racism and megalomania led to a rebalancing of other powers against him, the destruction of Germany and all the accompanying horror of World War II.

The postwar bargain

The generation that designed the post-Second World War order — American diplomat George Kennan, US Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, US Secretary of State Dean Acheson, European statesman Jean Monnet, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer — understood the structural problem that had produced 1914 and 1939. Europe by itself could not solve “the German problem”: how to keep the central power rich, integrated and secure without allowing it to dominate the continent.

The solution was an audacious two-level bargain. At the European level, Western Europe built institutions — the Coal and Steel Community, the Common Market, the European Union — to bind Germany into a web of mutual dependence and make war between France and Germany “not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible,” as French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman put it.

At the transatlantic level, the US did something no previous great power had done: it stationed large combat forces permanently in Europe and promised, in effect, to risk nuclear war for allies whose territory it did not covet. Through NATO, Washington offered a hierarchical but broadly benevolent order. The United States would act as the security provider of last resort, the de facto police force of the North Atlantic area.

In Waltz’s terms, the system remained anarchic — there was still no world government — but the presence of a dominant, relatively benign hegemon softened anarchy for its friends. Smaller and medium powers did not have to arm to the hilt. They did not need to carve spheres of influence because American naval predominance and liberal economic rules underwritten by Washington secured access to markets, sea lanes and raw materials.

Germany, in this system, could afford to be “abnormal.” It could renounce nuclear weapons, keep defense spending modest, and cultivate an identity as a “civilian power” and “trading state.” It built cars, machines and chemicals rather than aircraft carriers and ballistic missiles. The postwar “economic miracle” depended on that order, and so did political normalization. The Germany we know — democratic, export‑driven, allergic to nationalism — is a product of the US‑dominated liberal order, not a timeless essence of the German soul. The question is how long such an abnormality can survive if the order that sustains it decays or turns hostile.

Trump and the rebirth of Wilhelm II

Enter Trump — and, as Davos reminded Europeans this week, a US that increasingly resembles Wilhelm’s Germany: still powerful, but led by a man whose impulses and public statements are so erratic that no one can be sure what he will do next. Trumpism’s challenge is not merely that an American president insults allies or demands more European defense spending.

The deeper challenge is that Trump rejects the very logic of the post-1945 order. He sees alliances as protection rackets. He does not believe in a community of democracies or in “the West” as anything more than a slogan. He has repeatedly praised authoritarian leaders, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, and treated the EU as an economic enemy. Tariffs on European steel and aluminum, threats against German cars, the talk of “taking” Greenland from Denmark, and now an unhinged Davos performance in which he hectored and threatened Europeans are not isolated episodes. They signal a worldview in which might makes deals, not rules. Like Wilhelm II’s outbursts, Trump’s speeches are not just embarrassing; they are structurally destabilizing, because they make it impossible for allies to take American commitments at face value.

If a president toys with letting Russia “do whatever the hell they want” to allies that do not spend enough, muses about withdrawing from NATO or treats Article 5 as optional, he effectively breaks the alliance, whether or not he formally leaves it. Even if a future American president signals a return to the era of the Pax Americana, the memory of how quickly that commitment can be broken will not fade. Waltz’s abstraction — anarchy — ceases to be a seminar concept and becomes a lived condition. If Germany no longer believes in the permanence or good faith of the American security guarantee, it must relearn the lessons of Bismarck and Wilhelm II. It must ask how to survive in a world with untrustworthy great powers to its east and west.

Economic relations and hedging

The Davos meetings underscored this new mood from another angle as well. In a widely noted intervention, former Bank of England governor and now Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney argued that international economic relations can no longer rest on a simple community of “shared values.” Instead, he suggested, they are becoming layered and differentiated: at one end, deeply integrated ties with genuinely like-minded partners; at the other, arm’s-length, heavily transactional relationships with states whose values diverge. If the US is no longer a reliable, value-based partner, Carney implied, Europe and Canada will have to treat it much as it has historically treated authoritarian or quasi-authoritarian powers: cooperate where necessary, but hedge, compartmentalize and never entrust vital interests entirely to Washington’s goodwill.

In the near term, German responses will be constrained by history, law and political culture. The Basic Law, the trauma of the Nazi past and decades of antimilitarism still matter. No one in Berlin will announce a German bomb tomorrow. Instead, the first phase of adjustment will occur within the EU and NATO, even as the spirit of those structures changes.

We already see the outlines. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Chancellor Olaf Scholz proclaimed a Zeitenwende, a turning point, and announced a €100 billion fund to modernize the Bundeswehr (the German armed forces). Germany has promised to meet NATO’s 2% of GDP benchmark. German industry is rapidly expanding arms production. Berlin is knitting itself into a denser web of cooperation with Poland, the Baltic states and the Nordics. With Finland and Sweden now in NATO, a northern and eastern security belt is forming with Germany as a central hub.

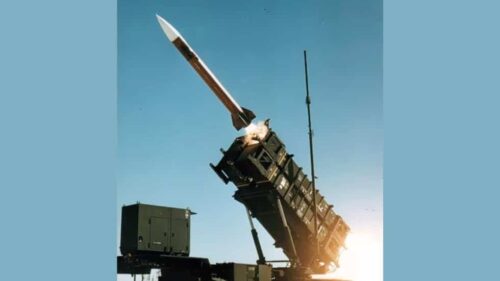

All of this happens under familiar EU and NATO logos, but the underlying strategy is shifting. These arrangements are less about reinforcing an American-led “European pillar” and more about hedging against American withdrawal or caprice. A serious turn to self-reliance implies large conventional forces for territorial defense, deep stocks of ammunition and fuel, integrated air and missile defenses, and indigenous capacity in critical technologies such as cyber, space and AI so that the United States cannot simply cut Europe off.

If pushed far enough, Germany, Britain, France and Poland may feel compelled to consider nuclear options — whether through an explicitly “Europeanized” French deterrent or, eventually, German participation in nuclear decision-making independent of Washington. In this first phase, Germany remains formally inside the post-1945 order, but it is already behaving like a middle-sized military power preparing to act in an anarchic system.

Domestic politics and polarization

Foreign policy, however, does not emerge from theory alone. It is filtered through domestic politics. Here, the German picture is troubling. On the far right, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has grown from a protest party into a major force, vying in some polls for second place and now the strongest opposition in the Bundestag — an echo, structurally if not (yet) morally, of the Nazi Party’s leap in 1930. On the far left, parts of Die Linke and other groups remain deeply suspicious of NATO and the United States, often rationalizing Russian behavior. They oppose arms deliveries to Ukraine and demand negotiations that would, in practice, freeze Russian gains.

What is striking is that both extremes converge on a pro-Putin, anti-American position. The AfD criticizes sanctions on Russia, opposes military aid to Ukraine, and demands the removal of US troops and nuclear weapons. Segments of the left insist (ahistorically) that NATO expansion “provoked” Russia and present distancing Europe from Washington as the path to peace, while treating China’s cynical “peace plans” with naive and unwarranted seriousness. These forces remain minorities, but if Trump or a Trumpist successor continues to insult Germany, impose tariffs and flirt with Russian power, they will grow. Every act of American bullying confirms their narrative that the US is not a benevolent hegemon but a predatory empire.

For a time, Germany will try to square the circle: remaining in the EU and NATO while building the capacity to act alone if necessary. But there comes a point where form and substance diverge too far. If Washington openly questions Article 5, withdraws troops, weaponizes the dollar against German industry, and leaves Europe squeezed between Russian aggression and American caprice, Berlin will face brutal choices. It can cling to a hollow alliance and hope for a better US president. It can push for full European strategic autonomy with Germany at its core. Or it can act as a semi-detached middle power, hedging between blocs, cultivating ties with Russia and China, and building unilateral capabilities — possibly including nuclear ones — to ensure it cannot be coerced.

None of these options is attractive. All are worse than the post-1945 arrangement in which Germany could be both powerful and constrained, rich and modest. That is precisely the point. The liberal order, for all its hypocrisies, made possible a world in which Germany did not have to be a “normal” power — and in which its neighbors, and Americans, did not have to worry about German ambitions, because Germany had no structural incentive to develop them. The death of that order does not bring justice or freedom. It brings back normality — and normality for Germany has twice meant catastrophe for Europe.

Trumpism’s misguided strategy

Trump and his advisers believe they are correcting a historic imbalance. Their story is simple: America has been exploited by rich allies who free-ride on its defense while undercutting it on trade. Force the allies to pay up, threaten them with abandonment, bully them with tariffs, and they will finally behave.

That story is naïve. It misunderstands alliance politics: states do not accept permanent dependence on an unreliable protector. If they fear abandonment more than entrapment, they rearm and realign. It underestimates the structural consequences of American withdrawal: German and Japanese rearmament in response to Trump is not burden-sharing but the emergence of potential counterweights. Japan’s main concern is defending itself against China, with the First Island Chain as its central focus. But the uncertainty Trump has created has accelerated its militarization efforts.

The Trump doctrine ignores domestic blowback by humiliating and endangering both Germany and Japan. In doing so, the US strengthens precisely those forces that want to end the Atlantic alliance and align with Russia or China. And it miscalculates the long-run costs to the United States itself.

For three-quarters of a century, America has purchased unprecedented influence, security, and prosperity at a remarkably low price by underwriting an order in which Germany and Japan were rich, disarmed and firmly anchored in the West. To throw that away for short-term posturing is not realism. It is vandalism.

The great achievement of the American-led order after 1945 was that Germans, and their neighbors, did not have to think in Bismarckian terms: buffers, spheres, deterrence. The great danger of Trumpism, amplified in Davos and elsewhere, is that it makes such thinking rational again. We still have time to choose otherwise. Americans can decide that the modest costs of sustaining a liberal order are far lower than the enormous costs of confronting a rearmed Germany, a resentful Europe, a rising China and a revanchist Russia all at once. Germans can decide that rearmament should happen inside a revitalized Atlantic framework, not in a lonely space between hostile empires.

But to make those decisions honestly, we must stop pretending that Germany will remain forever what it has been since 1945: a gentle economic giant that declines to act like a power. In a world where the sheriff holsters his badge or, like Wilhelm II, fires wildly to impress the crowd, there are no such giants. There are only states, some large, some small, all arming as best they can. If we insist on dismantling the order that made an abnormal Germany possible, we will get the normal Germany that history teaches us to expect. And then we will discover, too late, that the world we walked away from was not a burden but a bargain.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment