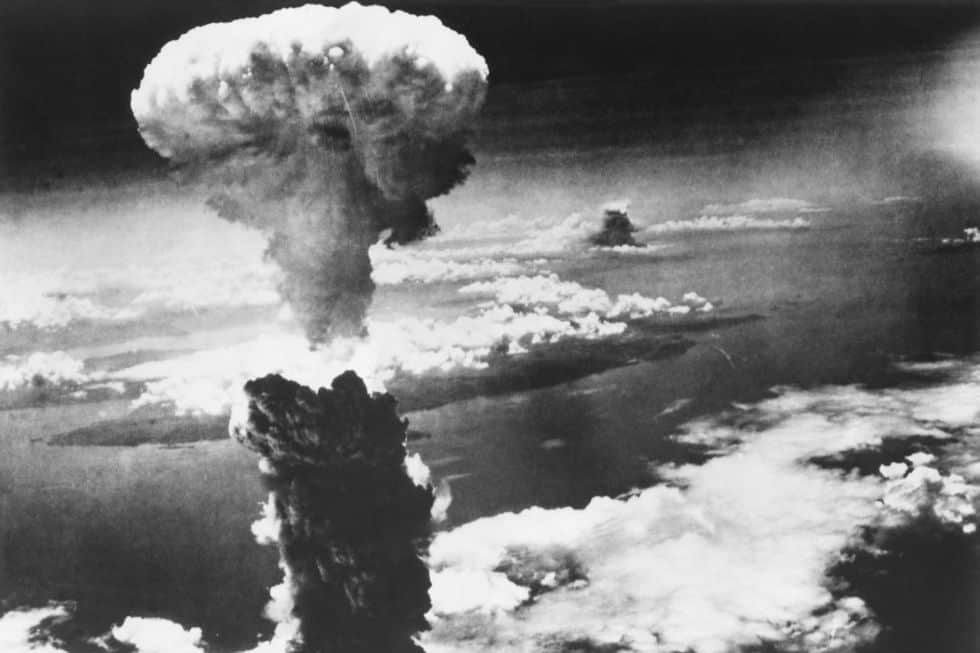

The dropping of an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, was a key event of the 20th century. The obliteration of Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki — with a total of over 100,000 immediate deaths and an even greater number of victims suffering from radiation — raised fundamental ethical and moral questions that are still controversially debated. At the same time, the destruction of an entire city by a single bomb revolutionized modern warfare, as it ushered in the age of nuclear deterrence.

With the “absolute weapon,” as American strategist Bernard Brodie put it as early as 1946, the primary goal of armed forces should no longer be to win wars, but to prevent them. However, many observers consider a strategy of war prevention based on the threat of nuclear annihilation to be incompatible with the moral and legal principles of proportionality or the protection of non-combatants in war. The central criticism, however, is that the system of nuclear deterrence forces all of humanity to live in a constant state of fear.

Given such fundamental questions, the atomic bombings of 1945 are no longer just about the political or military decisions made at the time. The answer to the question of whether the use of the bombs was justified also determines whether one fundamentally approves or rejects the system of nuclear deterrence as a means of preventing war. It is no longer possible to view these events independently of such ideological considerations.

The nuclear debate: Traditionalists vs revisionists

To this day, historians and political scientists continue to engage in a bitter dispute over the events of August 1945. “Traditionalists” argue that the bombs brought about Japan’s rapid surrender, thereby sparing the United States an invasion of Japan that would have cost the lives of many thousands of American (and Japanese) soldiers. Hence, Former US President Harry Truman’s decision to drop the bombs was the right one. Only later did the ethical dilemmas arising from the bombing become fully apparent.

“Revisionists” argue that the bombing was unnecessary, as Japan would have surrendered soon anyway. They claim that it was the Soviet Union’s entry into the war, rather than the bombs, that made Japan’s surrender. Moreover, the US only used the bomb to impress Stalin with a display of power and to conduct the post-war negotiations from a position of strength. Although this alternative interpretation of events has found many adherents, it remains highly problematic, as it replaces missing evidence with bold speculation and, above all, judges the actors of that time with the benefit of hindsight.

The struggle between traditionalists and revisionists continues, as it has become a battle for America’s past. However, in one important respect, international politics follows the traditional view of the events of that time: the system of mutual nuclear deterrence that emerged after the Soviet Union acquired the bomb in 1949 is based primarily on the horror of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The fear of a nuclear inferno shapes international politics by injecting caution. Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s 1955 observation that in the nuclear age “safety will be the sturdy child of terror, and survival the twin brother of annihilation” remains true today.

The dimensions of nuclear deterrence

Nuclear deterrence does not come about solely by the cautionary images of bomb victims or the mere existence of the bomb itself. To deter an opponent, the defender must threaten reprisals that the potential attacker perceives as credible. It also requires that a nuclear arsenal must remain intact and undestroyed during a surprise attack. Generations of scientists, mostly from the US, have therefore endeavored to explore the phenomenon of nuclear deterrence in all its dimensions.

While the first analyses following Hiroshima focused on the strategic implications of nuclear weapons for international relations, the scope of deterrence research expanded significantly in the 1950s. Using game theory and behavioral psychology, researchers investigated how rationality — the functional condition of nuclear deterrence — is reflected in political and military decisions. During this period, they also developed the conceptual foundations of nuclear arms control.

In the early 1970s, a new field of research emerged, focusing on case studies of nuclear crises and the decision-making processes of political and military elites. These more empirically and historically oriented studies showed that some earlier deterrence works were far too abstract to reflect complex realities. By highlighting the different interests and emotions of the actors involved, this field of research raised awareness of the need to consider cultural differences as well as the risk of misperceptions. Above all, however, it brought into sharper focus that nuclear deterrence is not a panacea: it may be able to prevent some, but not all conflicts.

The next steps for nuclear deterrence

Today, countries are working on extending the concept of deterrence to space, cyberspace or hybrid warfare. However, as the growing number of cyber and hybrid attacks demonstrates, the deterrence paradigm, let alone its nuclear dimensions, sits uneasily with non-military threats. A stronger focus on resilience may offer greater security benefits.

The next step for deterrence research is already becoming clear, however: How to organize nuclear deterrence in a world with three or more major nuclear powers. For example, China will soon have caught up with the nuclear arsenals of the US and Russia, turning nuclear deterrence into a complicated equation with many unknowns.

Deterrence research will always face accusations that it ultimately maintains a dangerous and immoral system that deliberately accepts mass murder. For decades, the orthodox school of thought, which views nuclear deterrence as a strategy for preventing war, has been accused of being a closed community that refuses to question its assumptions. Furthermore, the critics say that the nuclear weapons discourse employs emotionless language that feigns rationality, reducing nuclear mass murder to mere “collateral damage” and thus obscuring the terrible consequences of its policies.

Continued debate and a search for alternatives

Since the beginning of the nuclear age, critics have attempted to expose nuclear deterrence as a misguided approach. Arguing that the mere existence of nuclear weapons will eventually result in their use, they have put forward a host of arguments why the abolition of these weapons is the only rational conclusion.

However, thus far, at least, all the alternatives suggested by deterrence critics have had no lasting political impact. This lack of longevity is due less to resistance from the nuclear technocracy than to the alternatives’ analytical weaknesses: they sound convincing in theory, but fail in reality.

One such example is the argument that nuclear weapons could be abolished by changing societal norms, as was the case with slavery. However, such comparisons are flawed, as not all norms are equally strong. Abolishing slavery was a moral goal in itself, whereas abolishing nuclear weapons is not. As long as people believe that such weapons provide security, they will require more than a shift in societal attitudes for their abolition. Nations will need to establish alternative means of security that they can all agree upon — alternatives that currently remain elusive.

The idea of outlawing nuclear weapons is equally oversimplistic. Although the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which stigmatizes nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence as illegal, came into force in 2021, it remains ineffective, as none of the nuclear powers or their allies have signed it. The anti-Western stance of some of its prominent supporters and some flawed treaty language had made the Treaty questionable from the beginning. Numerous nuclear threats accompanied Russia’s assault on Ukraine, further marginalizing that project.

Some critics of deterrence have sought to push an entirely different line of argument. They argue that the bomb is simply irrelevant and, hence, they can abolish it without any loss of security. However, in their attempts to demonstrate the irrelevance of nuclear weapons, they employ dubious logical leaps and implausible interpretations of historical events.

Above all, real-life events, such as Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the recent destruction of many of Iran’s nuclear installations by the US and Israel and the debate on the reliability of the US “nuclear umbrella” for Europe, have brought home that the theory of irrelevance is, well, irrelevant.

There are even more perspectives to criticize nuclear deterrence, from investigative reporting on accident-prone nuclear infrastructure to highlighting the “systemic injustice” of the nuclear deterrence system, such as the insufficient attention given to the health problems of people living near former nuclear testing sites.

Each of these approaches has some validity: Exposing nuclear safety shortcomings serves as a constant reminder that the nuclear enterprise must adhere to the highest safety standards, while emphasizing the long-term effects of nuclear testing shows that nuclear weapons carry hidden costs that go well beyond what the official defense budgets list.

Yet none of these criticisms have been powerful enough to effect a major change in the national security and defence policies of Nuclear Weapons States, their allies, and possibly many more that expect at least some indirect protection from nuclear deterrence.

80 years later

80 years after Hiroshima, the debate about the wisdom of dropping the atom bomb continues. Yet, the system of nuclear deterrence that emerged after 1945 has become a major element of international politics.

Critics will continue to point to the moral and conceptual flaws of nuclear deterrence and demand the abolition of nuclear weapons. However, they are unlikely to prevail against the view that, to quote Thomas Schelling, a non-nuclear world would be “a nervous world”, as each crisis could compel countries to (re-) acquire a nuclear capability. “The urge to preempt would dominate; whoever gets the first few weapons will coerce or preempt.”

Nuclear deterrence remains a major factor in international politics, as long as mankind has not found a better way to prevent war, even though it is not foolproof. Even 80 years later, the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continue to induce restraint in international relations.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment