Over the past decade, street protests in Iran have erupted repeatedly. At times, economic crises have served as the main trigger; at other moments, political repression or regional tensions have pushed people into the streets. Yet despite the changing causes, the overall pattern has remained strikingly consistent: demonstrations that spread rapidly, a surge of nationwide anger and ultimately a forceful state response that suppresses the unrest. This recurring cycle raises a central question — not only about the depth of public discontent in Iran, but also about why these protests have so far failed to produce lasting political transformation.

In the early days of the new year, the Islamic Republic of Iran found itself in one of its most fragile periods in recent history. Fresh protests had once again erupted across several cities, reflecting a familiar pattern of public anger triggered by economic hardship, political repression and regional tensions. International sanctions imposed over the past decade have severely weakened the country’s economy, while soaring inflation and rising living costs have directly affected the daily lives of large segments of society. When these economic pressures intersect with long-standing political restrictions, street protests cease to be extraordinary events and instead become a recurring form of social expression.

In the early 2000s, demonstrations tended to revolve around more limited demands, particularly women’s rights, compulsory veiling and individual freedoms. Today, however, under the shadow of economic collapse and regional conflict, protests have taken on a far broader and more pervasive character.

Economic pressure and the expansion of social unrest

One of the most extensive waves of nationwide protests since the 1979 Revolution erupted across Iran in November 2019, marking a significant escalation in public dissent. As the economic impact of Western sanctions became increasingly visible, the government’s decision to sharply raise fuel prices triggered simultaneous demonstrations across multiple provinces. Within days, protests spread to dozens of cities, with anger no longer directed solely at economic policies but increasingly at the political system and its decision-making structures. University students also joined the demonstrations, further amplifying their scale.

The authorities responded with force. Reports from human rights organizations indicated widespread use of lethal violence by security forces in cities such as Shiraz, Isfahan and Kermanshah. According to Amnesty International, at least 321 people were killed by security forces during the November 2019 crackdown. President Hassan Rouhani publicly framed the unrest as a major security challenge, blaming “organized subversive elements” and foreign adversaries, a response that underscored how seriously the state viewed the protests as a threat to internal stability.

A crisis of legitimacy and state violence

Allegations surrounding state violence during the 2019 protests extended beyond the streets. According to international human rights organizations and eyewitness accounts, authorities attempted to underreport the number of fatalities, imposing strict controls over hospitals and morgues. Some reports claimed that families of deceased protesters faced pressure or financial demands in exchange for retrieving the bodies of their relatives.

In January 2020, protests entered a new phase as different social groups joined the unrest. Taxi drivers and shuttle operators took to the streets over fuel price hikes, soon followed by railway workers protesting low wages and farmers struggling under mounting economic pressure. The protests thus evolved into a broader social movement centered on livelihood concerns rather than on political or cultural demands alone.

A further turning point came with the downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane by Iranian air defense systems, killing 176 people. The authorities’ initial denial and subsequent admission of responsibility deepened public distrust toward the state. Protest slogans increasingly reflected anger not only toward government policies but toward the highest political and religious authorities themselves.

Women, identity and a new form of protest

In September 2022, the death of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, after her detention by Iran’s morality police, reignited nationwide protests. The incident brought long-simmering grievances over compulsory veiling and women’s status in public life sharply into focus. Although the protests followed a different trajectory than those of 2019, they persisted well into 2023 and coalesced around the slogan “woman, life, freedom.”

This time, the regime faced direct challenges on the terrain of women’s rights and individual liberties. Women removing their headscarves in public spaces, particularly in Tehran and other major cities, imbued the protests with strong symbolic power. With support from Kurdish and Azeri communities, the women-led movement rapidly spread across the country, further broadening the social base of dissent.

Why political transformation has yet to occur

Despite the persistence and scale of popular unrest, Iran has yet to witness the emergence of a political alternative capable of uniting disparate social groups and challenging the regime’s hold on power. Protests organized largely through social media remain fragmented and leaderless, lacking the centralized authority that Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini was able to exert even from exile in 1979.

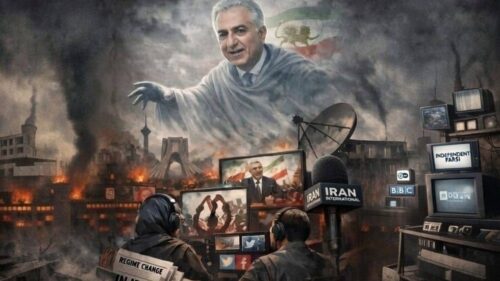

Prince Reza Pahlavi, the son of the former shah and a figure occasionally highlighted within opposition circles, enjoys visibility particularly among segments of the Iranian diaspora. However, he has struggled to establish a strong connection with domestic opposition movements. His political stance is widely perceived as overly aligned with the West, detached from Iran’s everyday social and economic realities, and burdened by the legacy of his father’s authoritarian monarchy — factors that generate caution rather than enthusiasm among broad sections of the population.

Similarly, while Azeri communities and the Kurdish minority — together comprising a significant share of Iran’s population — harbor deep dissatisfaction with the clerical regime, they remain equally distant from the idea of restoring the former monarchy. This disconnect between diaspora-based opposition figures and diverse domestic constituencies stands out as one of the most significant structural weaknesses of Iran’s anti-regime movements.

A narrowing circle, an enduring search

Today, Iran’s clerical regime remains in power, yet it is undergoing a steady process of erosion. Economic collapse, escalating protests over freedoms and women’s rights, ethnic tensions and mounting pressure from Israel, the United States and Western governments are collectively straining the system. Recent experience suggests that protest movements lacking organizational cohesion and unified leadership tend to fade in the short term. However, a regime that relies primarily on coercion to sustain its authority faces growing difficulties in maintaining long-term social control.

Limited and pragmatic support from actors such as Russia and China may provide Tehran with temporary strategic breathing space. Nevertheless, as economic vulnerabilities deepen and internal tensions intensify, preserving this balance becomes increasingly challenging. The overall picture points to a slowly but steadily tightening circle around the Iranian leadership.

Taken together, these developments suggest that the demand for freedom, dignity and justice in the ancient land of Persia is not a fleeting political outburst but a profound and enduring social aspiration. While the costs and trajectory of this struggle remain uncertain, history repeatedly calls into question the durability of political systems sustained primarily through repression. In this sense, the words of Iranian sociologist Ali Shariati resonate far beyond Iran itself:

“In a country where only the state is allowed to speak, do not believe a single word that is said.”

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment