What America wouldn’t give to turn back the clock to February 23, 2022, and make a bold, controversial and possibly unpopular military decision that could have stopped the Russian invasion of Ukraine before it began. To act pre-emptively, decisively, even provocatively; to risk being accused of escalation, warmongering and sticking its cowboy boots where they don’t belong.

At that moment, equipped with credible intelligence assessments predicting the invasion, the world’s policeman froze up. The West now lives in the consequences of its appeasement and excessive caution: a grinding, gruesome war, millions displaced, a fortune spent in blood and treasure.

No one is yet in a position to conclusively determine how much the recent American strike regressed Iran’s nuclear program, but that might not be the final and best determinant of its effectiveness. The better question is, did it scare the right people?

The preparedness paradox

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Western democracies suffered from the preparedness paradox. This paradox occurs when preventative measures, preparations and mitigation efforts are so effective at preventing catastrophe that observers mistakenly conclude the preparations were unnecessary or wasteful.

Because nothing bad happened, people start to assume nothing would have happened even without the preparations — giving in to what I term a “causal oversight fallacy.” Ironically, as a result of this false sense of security, decision-makers often reduce preparedness, which can invite the very crises that the initial measures had successfully deterred.

The erosion of deterrence is far from the only example of the preparedness paradox that afflicts us. It can also be seen when, after decades of rigorous fire safety codes and few fatal fires, a city decides to reduce the stringency and enforcement of fire safety regulations, which was a causative factor in London’s Grenfell Tower fire, with its death toll of 72 people.

Since the West had not faced a total war for nearly a century, it increasingly viewed its armies as a vestigial appendage, allowing for attrition in pursuit of other goals. This perception diminished Western psychosocial readiness for war and led Western leaders to shun hard power, even in cases where all the alternatives proved ineffectual.

This is part of a broader failure on the part of democracies to adapt to modern warfare. Modern wars are (with few exceptions) not total in nature — the full force of either side is usually left to the imagination. For many decades, democratic states have rarely fought other states, and increasingly confront nonstate actors (the primary agitants in conflict for well over a decade). Counterinsurgency campaigns go against American warfighting psychology and that of democracies more broadly, which nonstate actors exploit to gain the psychological and political upper hand. As a result, Western forces often stumble into pitched battles — and leave without clear victories.

American deterrence has been further attenuated by its fleeting or fumbling shows of strength and humbled by its own extravagant signalling. The country suffers from a version of the preparedness paradox compounded by unusual political and cultural challenges around future threats. Recent events, such as the Texas floods, demonstrate that even awareness of a threat doesn’t guarantee it will be prioritized. This is why, although Russia’s invasion of Ukraine logically should have startled the West into a full awareness of the need to prevent wars by preparing for them, deterrence still floundered right up until the strike on Iran.

Executive power and politics

Two of the most controversial leaders in the democratic world — Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and US President Donald Trump — orchestrated this strike, heightening the public perception of caprice or executive overreach. Both leaders have destabilized democratic norms in different ways and to varying degrees, leaving a track record of democratic backsliding, broken promises and legal transgressions. Both are so hated by some constituencies that any major action they take will elicit criticism.

For Netanyahu, Iran has always been the career-defining threat — a rallying cry across his decades in politics. From 1996 to the Israeli airstrikes, which “softened the target” at Natanz, his escalation against Iran was, if not entirely predictable, unsurprising. While over half disapprove of Netanyahu himself, Israelis overwhelmingly support the recent military actions against Iran.

Trump is a different case entirely. His past actions — such as withdrawing from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018 without a better plan, repeatedly undermining NATO and oscillating on US troop commitments — have measurably harmed US credibility abroad. He aligned with a heady anti-interventionist base during his campaign, promoting an “America First” agenda that seemed to abdicate America’s role in anything foreign (unless there was a dollar to be made). Yet in this case, he chose bold action over bluster, domestic fallout be damned.

Given the noxious nature of the politicians involved, would I and others in my field have dared to offer such a full-throated defense of the decision to strike Iran if the results had been less agreeable? In a perfect world, yes; in reality, probably not.

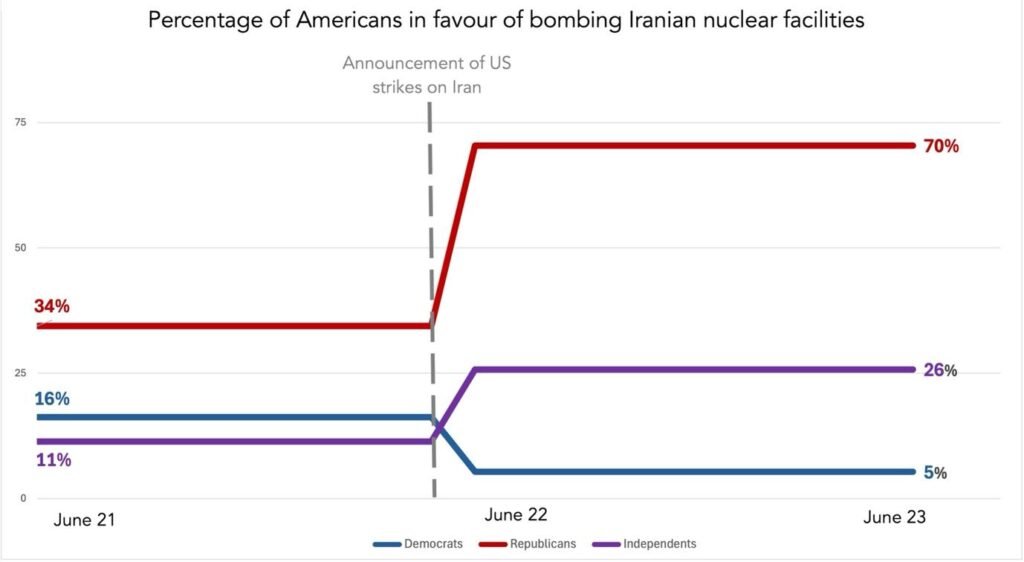

To the torment of statisticians the world over, humans tend to misinterpret the outcome of events to form unfounded beliefs about the underlying probabilities at play (a phenomenon known as outcome bias). Success doesn’t negate the risks involved — and failure wouldn’t have automatically discredited the decision. In this case, the people who took the action, and the action’s perceived success, seem to be having an outsized impact on public perception (see fig. I), while the underlying strategic calculus falls by the wayside.

These fluctuations in public opinion may hamper efforts by America and other democracies to reestablish deterrence, rein in rogue states and chart a coherent strategic course. Recognizing that kinetic operations may not always go smoothly — and that even successful ones can provoke fierce criticism — creates a strong internal deterrent for risk-averse politicians within any democratic nation (worsening the underlying status quo bias). The lack of political will among traditional politicians to address the gradual disintegration of a credible deterrence posture, demonstrated by the fact that only an extremely unorthodox US leader acted against a significant and long-standing threat to national security, stands as a warning to the democratic establishment: democracies have ignored deterrence at their peril.

Rather than taking this as a moment for recalibration and self-reflection, the democratic orthodoxy has lashed out with a willful strategic blindness. Opposing politicians acted cynically, even hypocritically partisan, and while the War Powers Vote had an understandable motive (reining in a painfully unpredictable and power-hungry executive), it demonstrated an outrageous lack of consideration for the safekeeping of broader American strategic objectives. From a deterrence perspective, the worst possible move after a provocative action is to reduce the perceived risk of retaliation in the mind of the target.

Troublingly, 63% of Americans polled afterwards said that Trump needed congressional approval for the strikes. Still, at the same time, 56% said that Iran having a nuclear weapon would be a threat to the security of the United States. The problem: there is no mechanism for Congress to debate and approve strikes when the success or failure of those strikes depends entirely on maintaining secrecy and catching the target off guard.

Debating and publicly approving a strike would render it moot because Iran would immediately relocate its most essential stocks and components away from the targeted locations. This action would also significantly increase the likelihood of casualties on both sides, and create the perception that Iran and America were going to war, which would, ironically, set both on course for an actual war. Congress is many things, but an effective architect of deterrence posture is not one of them, and assigning it that responsibility would be disastrous.

The broken link

There is another problem hiding in plain sight: something is very wrong inside the body of the United States security apparatus. Watching America decide to strike was like watching an animal walk with a dislocation — the US intelligence community being the dislocated appendage.

In the weeks leading up to this strike, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard testified before Congress that Iran was not actively on the path to a nuclear weapon. Gabbard, the lead anti-interventionist in this Trump cabinet, has used her brief and controversial tenure to undermine the independence of the analytic process and shape intelligence products to political ends.

Chosen by a president with a profound distrust of the intelligence community, Gabbard was unleashed on the world’s most vaunted spy agencies with a mandate that would slowly destroy their credibility. But then, in a strange case of a flawed process yielding a correct outcome, Trump ignored that assessment altogether (and Gabbard later publicly reversed her position).

Even if the recent assessments were not irreparably contaminated by the environment in which they were produced, American intelligence has a checkered history with Iran. The 1979 Islamic revolution blindsided the US so badly that it left its embassy staff directly in the morass, resulting in a humiliating 444-day hostage crisis.

There is an uncomfortable possibility that looms that, in the shadow of the Iraq weapons of mass destruction (WMD) intelligence failure — which erred in the opposite direction — the intelligence community once again overcorrected, exercising excessive conservatism in its assessments of Iran. It would have been reckless to do nothing on the hope that the American analysts got it right this time, especially since, if that had been the case, the rest of the world would have been horribly wrong.

Prior to the strike, the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) had issued a series of increasingly urgent assessments, warning about rising uranium enrichment levels, restricted inspector access and suspicious activities at undeclared facilities. They ultimately declared Iran noncompliant in June 2025. Key allies such as France had also issued warnings, along with multiple security-focused think tanks. In private intelligence briefings, assessments were reportedly sharper than what was being publicly released, particularly after Iran stonewalled the IAEA and missile test activity intensified.

Even in a typically fractured information environment, American intelligence assessments leading up to the strike seemed oddly out of sync. They relied more on assertions of Iran’s benign intentions than sober assessments of its rapidly advancing capabilities, despite a clear trend in the Iranian nuclear program’s troubling history and the fact that there are no civilian uses for uranium enriched to these levels.

The strategic case for a strike

Since Iran has never been a nuclear power, it is impossible to know how it would behave with such dangerous weaponry, but its past behavior offers cause for concern. It is very likely that in considering the scenario of a nuclear Iran, many beyond the Middle East fall prey to normalcy bias, assuming that things will continue as they always have, with Iran as a state sponsor of proxy militias, terrorism and cybercrime around the globe, but not an existential threat to anyone but its neighbors.

According to the preponderance of analyses (and of course, the revised American assessments), this strike occurred during the last narrow window before the strategic calculus would have shifted irreversibly. In this case, the radiation was contained; not so if Iran had crossed the nuclear threshold. Delaying a strike until that point would have magnified the risks exponentially, forcing a choice between effectively setting off nukes in Iran or risking them detonating in Israel.

The alternative to military action against Iran — diplomacy — had long since become a euphemism for a meaningless political circus. For over two decades, the world has debated whether to tolerate, delay or dismantle the regime’s forays into nuclear science, while Iran made a mockery of negotiations. By 2023, Iran was already producing an approximation of weapons-grade uranium. There was no question that Iran had amassed enough highly enriched uranium (HEU) to build multiple bombs in a matter of weeks.

The repercussions of America’s strike in the late hours of June 21st extend far beyond the Middle East. America’s willingness to return after two decades of draining conflict in the region must have surprised many adversaries. For Russia, still entrenched in its costly and grinding invasion of Ukraine, the strike flies in the face of its narratives about the West’s frailty and impotence. It might afford a second chance for Trump to make good on his seemingly abandoned campaign promise of ending that war.

It will be extremely difficult to reverse Putin’s entrenched position, but in Beijing, which has not yet committed itself to a specific timeline for its long-anticipated land grab, this unpredictable American hard-power projection may delay a possible invasion of Taiwan. In one of the many ironies of the moment, this bombing recalls, however imperfectly, the aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki — not in scale or devastation, but in effect.

In August 1945, the willingness to use overwhelming, paradigm-altering military force recalibrated the global balance and ushered in the Pax Americana (the period of relative peace, from circa 1945, in areas where the United States has exerted significant influence). Imagine if even a fraction of that effect could have been achieved not by using nuclear weapons, but by preventing their creation. While this dark comparison may be loathsome, it is also instructive: overwhelming force remains the only mechanism to deter a truly committed adversary.

If America’s strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities achieves a long-term strategic goal, it will probably derive from the reintroduction of an almost anachronistic element into the global security equation: the looming threat of American power projection against state actors. Deterrence only works when it is credible, and true unpredictability (as opposed to Vladimir Putin’s theatrical nuclear brinkmanship, which Trump is now mimicking) can be a powerful tool for creating uncertainty in the minds of adversaries, confusing or frightening them into restraint.

There is much to be gained by reigniting the fear that America might actually use its tremendous military might, not in flailing off-brand counterinsurgency campaigns, but in the kinds of theaters it was built to dominate.

[Kaitlyn Diana edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment