The International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s External Sector Report (ESR) 2025, published last year on July 22, delivers a stark warning: After more than a decade of narrowing global current-account imbalances following the financial crisis, these imbalances widened significantly in 2024. According to the ESR, global current-account balances expanded by approximately 0.6% of world GDP, marking a reversal of the previous downward trend. Adjusted for the extraordinary shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, the swing appears even more substantial. Rather than a fleeting blip, the IMF suggests this may herald a structural shift in how savings, investment and trade flows interoperate.

The scale of the analysis adds weight to the finding. The ESR covers 30 of the world’s largest economies, representing about 90% of world output. It concludes that much of the 2024 widening reflects what the IMF calls excess imbalances: external positions that deviate meaningfully from what country fundamentals and policy settings would warrant. Thus, the concern is not merely that surpluses or deficits exist, but that their magnitude and persistence signal underlying distortions in saving and investment behaviors.

To strengthen causal clarity, it is worth noting that these spillovers arise through interest-rate channels, exchange-rate movements and global liquidity cycles that amplify the asymmetry between surplus-driven capital exports and deficit-driven capital absorption.

Macro-financial risks reemerging

This resurgence of economic divergence reawakens familiar risks that have long characterized global macro-financial cycles. Economies with sustained current-account deficits remain vulnerable to abrupt reversals in capital flows, sudden increases in borrowing costs and the pressures of forced adjustment. Conversely, economies with persistent and sizable surpluses may inadvertently suppress global interest rates, channel excess savings abroad and weaken aggregate demand in deficit economies. These opposing dynamics reinforce each other: Liquidity constraints in deficit nations coexist with excess savings in surplus economies, magnifying volatility and mispricing of risk.

The IMF’s ESR 2025 stresses this dual-risk framework, warning that “delaying macro-economic adjustments to correct post-pandemic domestic macro-imbalances could result in continued current-account divergence in major economies.” Moreover, the report emphasizes that “such rapid and globally sizable increases in excess current-account balances can generate significant negative cross-border spillovers,” underscoring that imbalances on either side of the external ledger contribute to systemic fragility and threaten the cohesion of the international monetary system.

The IMF research, notably under the direction of IMF Chief Economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, reinforces this perspective by demonstrating that external surpluses are not inherently the “safe side.” His paper shows that large, persistent surpluses can depress global equilibrium interest rates, entrench savings gluts and exacerbate liquidity traps in an interdependent world economy. In this framework, creditor nations export their safe-asset status and, in doing so, inadvertently heighten global fragility. This finding directly aligns with the IMF’s concern that systemic risks arise not only from deficit economies, but equally from those with sustained surpluses.

A structural break, not simply a rebound

The year 2024 marked not a cyclical rebound but a structural inflection in global current-account dynamics. What distinguishes this episode is not only the magnitude of the widening but its asymmetric composition and global reach. Major surplus economies — particularly China and parts of East Asia — expanded their surpluses, while major deficit economies, led by the United States, deepened their shortfalls.

The IMF’s ESR 2025 estimates that about two-thirds of the widening in global current-account balances was “excessive,” meaning inconsistent with countries’ structural fundamentals or cyclical positions. When these excess balances are excluded, the underlying widening falls to roughly 30% underscoring how far the current trajectory diverges from equilibrium drivers such as demographic trends, fiscal stances or commodity prices.

Although the pattern resembles the mid-2000s surpluses and deficits, today’s environment differs crucially — China’s reserve accumulation is smaller relative to GDP, macroprudential regulation is stronger and global capital is shaped more by risk-management frameworks than by unregulated financial intermediation. These differences caution against overly direct comparisons while still supporting the argument that the widening is structurally driven.

The composition of these shifts reveals the extent of renewed structural divergence. China’s external surplus expanded by about 0.24% of global GDP, the US deficit deepened by 0.20% and the euro area added roughly 0.07%; together, these factors account for the majority of the global imbalance. This pattern evokes the mid-2000s configuration, when Asian and commodity-exporting economies accumulated surpluses as the US ran record deficits — a prelude to the global financial crisis. Although today’s context differs — our current world is marked by subdued trade elasticity, altered capital flows and evolving reserve accumulation motives — the reemergence of excess balances suggests that global saving and investment asymmetries have again become entrenched.

The policy implications are sobering. The ESR 2025 cautions that raising tariffs or erecting trade barriers, though politically expedient in deficit economies, does little to narrow external gaps and may instead distort resource allocation, dampen productivity and intensify inflationary pressures. Durable adjustment will require deeper rebalancing: fiscal consolidation and higher household saving in deficit economies, coupled with stronger domestic demand and financial liberalization in surplus economies. The 2024 widening thus represents a structural reassertion of global asymmetry, one that challenges both the resilience of the international monetary order and the credibility of its adjustment mechanisms.

A structural break in the global balance

The year 2024 marked a turning point in the world economy, a structural rupture in the global balance of payments. The sharp widening of global current-account gaps revealed deep-seated asymmetries: Surplus economies expanded further, while deficit countries fell deeper into shortfalls. This divergence reflected enduring mismatches between national saving and investment patterns rather than temporary business-cycle fluctuations. Data from the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) Tracker show that these disparities accounted for a significant share of world GDP, with surplus and deficit economies drifting further apart in 2024 — an imbalance shaped more by structural saving-investment behavior than by short-term trade trends.

At the root of these imbalances lie persistent domestic distortions. In surplus countries, precautionary saving remains elevated, social safety nets are underdeveloped and investment is overly concentrated in export-oriented sectors — constraining the transition toward consumption- and services-led growth. In deficit economies, dependence on external financing is reinforced by weak private saving and structural fiscal laxity — not in the sense of countercyclical stabilization, where temporary deficits play a productive role during downturns, but as a persistent feature of policy shaped by political economic constraints rather than macroeconomic necessity.

As highlighted in CFR’s commentary, the global pattern of imbalances increasingly reflects excess precautionary savings and limited policy adaptation in major economies. Europe continues to lag behind the US in productivity and investment dynamism, China’s consumption-driven transition remains incomplete and the US has delayed credible fiscal consolidation despite mounting debt pressures.

True rebalancing, therefore, requires structural reform, not external confrontation. Stronger social insurance systems could moderate excess saving; higher domestic investment could support innovation and productivity; and credible fiscal rules could anchor sustainability. Yet political responses have often moved in the opposite direction. The recent revival of tariffs and industrial policies in advanced economies represents a turn toward visible but misguided remedies. Such measures function economically as negative supply shocks — raising costs, discouraging investment and compressing real incomes — without improving the external balance. Protectionism, rather than correcting global asymmetries, risks amplifying domestic inefficiencies and undermining long-term welfare.

To avoid overgeneralization, it is important to distinguish investment-oriented industrial policy (which can raise potential output) from protectionist industrial policy (which typically functions as a negative supply shock). The latter is the source of imbalance-worsening dynamics.

At the multilateral level, policymakers have begun to acknowledge that external divergences are no longer adequately explained by bilateral trade flows, but by macro-financial incoherence across a fragmented global system. As capital flows become increasingly regionalized and supply chains realign, systemic fragility grows. Without coordination, what begins as national adjustment failure could evolve into global dislocation. To avoid this will require coherent fiscal, monetary and structural policies that recognize the spillovers of domestic choices on the international system.

The international monetary system, still anchored by the US dollar, remains stable but faces rising pressures. Its dominance is challenged by shifting geopolitical alliances, the proliferation of digital financial instruments and concerns over US fiscal sustainability. While confidence in dollar liquidity and institutions endures, global fragmentation risks raising transaction costs and financial volatility. The widening current-account imbalances of 2024 thus stand as a warning: Without domestic reform and renewed cooperation, the world risks turning structural distortions into systemic fault lines — testing both the resilience of the global order and the political will to sustain it.

The three pillars of domestic reform

While the IMF’s ESR Report diagnoses the reemergence of global current-account imbalances, the IMF–World Bank Annual Meetings helped to define the policy response. A consensus emerged around three domestic pillars: fiscal sustainability, public investment and productivity, and social insurance with demand rebalancing. Each pillar is supported by IMF analysis and cross-country policy assessments.

Deficit economies must restore fiscal space to reinforce confidence and resilience against shocks. The IMF’s Fiscal Monitor (Annual Meetings 2025) warns that “starting from too high deficits and debt, the persistence of spending above tax revenues will push debt to ever higher levels, threatening sustainability and financial stability.” The report stresses that fiscal consolidation and the rebuilding of buffers are essential to “prepare fiscal space to use in case of severe adverse shocks.” In practical terms, this means strengthening fiscal rules, prioritizing high-quality expenditure and improving tax efficiency. Fiscal frameworks that demonstrate medium-term discipline, rather than ad-hoc austerity, are the cornerstone for credible adjustment and reduced external vulnerability.

This distinction is important because excessive reliance on temporary or politically motivated fiscal expansions has historically weakened policy credibility, especially in high-debt advanced economies like Japan’s.

Surplus economies with ample fiscal capacity are encouraged to channel excess domestic savings into productive investment at home — particularly in infrastructure, digital transformation and green transitions. The IMF ESR 2025 notes that countries such as Singapore and Japan should “raise public investment and strengthen social safety nets to reduce external surpluses by lowering net saving in both public and private sectors.” Specifically, Japan is advised to “implement policies focused on structural reforms and fiscal sustainability through a credible and specific medium-term fiscal consolidation plan,” and to “shift the drivers of the economy to one driven by the private sector, raising potential growth through labor-market and fiscal reforms that support private demand, digitalization, and green investment.” Likewise, Singapore is urged to “execute planned high-quality and resilient infrastructure projects and continue strengthening social safety nets to help reduce external imbalances,” while “increasing public investment to address structural transformation brought by aging and the transition to a green and digital economy.”

Furthermore, the IMF Managing Director’s Global Policy Agenda (Fall 2025) underscores that “countries need to restore their depleted policy buffers” while pursuing “fiscal measures that promote medium-term growth through innovation and green investment.” Together, these recommendations imply that global rebalancing depends as much on the productive absorption of savings as on fiscal prudence — transforming surplus positions into engines of sustainable domestic growth.

Japan approach: responsible stimulus or fiscal risk?

Japan’s fiscal trajectory under Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi has emerged as one of the most revealing case studies in the post-pandemic evolution of macroeconomic policy. In sharp contrast to the consolidation trend prevailing across advanced economies, Tokyo has embarked on a renewed phase of large-scale countercyclical intervention — a fiscal package exceeding ¥13.9 trillion (approximately 2.4% of Japan’s GDP; $88.9 billion) aimed at alleviating cost-of-living pressures, accelerating real-wage recovery and revitalizing corporate reinvestment.

This deliberate pivot toward fiscal expansion is both pragmatic and experimental, reflecting Japan’s long-standing struggle with chronic deflation, rapid population aging and structural underinvestment in productivity-enhancing sectors. Yet these same structural forces that justify fiscal activism may also constrain its long-run effectiveness, raising questions about sustainability and market confidence. A central challenge is that Japan’s stimulus increasingly serves multiple objectives simultaneously — short-term support, structural transformation and political stabilization — which complicates the task of maintaining a coherent medium-term fiscal anchor.

The fiscal deficit for 2024 is estimated to be narrower than projected in the 2024 Article IV Consultation, as robust corporate earnings have buoyed tax revenues while pandemic-related transfers to households and small and medium-sized enterprises have been largely phased out. Nonetheless, the deficit is expected to widen moderately in 2025, reflecting new expenditures for defense, family-support measures and industrial-policy initiatives.

Given constrained fiscal space and mounting political pressures on the minority government, any additional expansionary measures must be fully offset through corresponding revenue gains or expenditure rationalization elsewhere in the budget. This offsetting requirement is especially important because repeated reliance on discretionary stimulus, without equivalent medium-term consolidation, risks weakening long-run fiscal credibility even if short-term financing conditions remain benign.

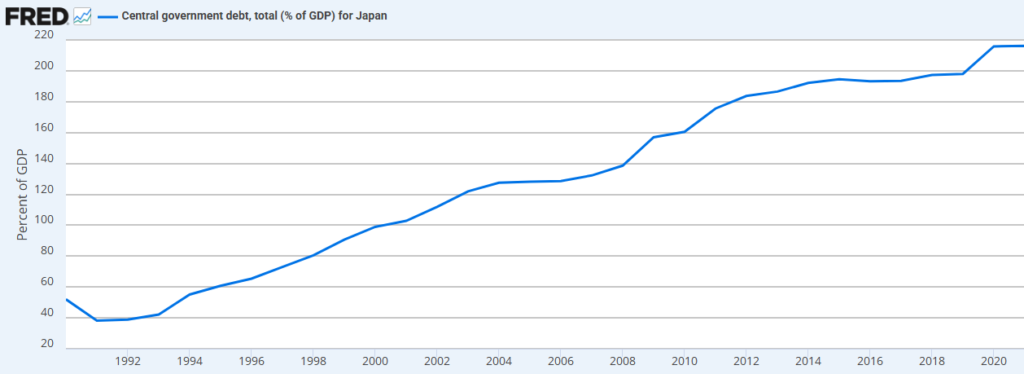

Public debt, while declining marginally in the near term as nominal GDP growth exceeds the effective interest rate, remains among the highest globally. In fact, it is projected to resume an upward trajectory by 2030. This rise is driven by a growing interest burden and escalating social-spending commitments related to healthcare and long-term care. Ensuring debt sustainability and restoring fiscal buffers will therefore require a credible and granular medium-term consolidation strategy anchored in durable institutional frameworks and transparent fiscal rules. The absence of such a framework increases the likelihood that future fiscal adjustments will be abrupt, procyclical or politically disruptive.

A coherent fiscal framework should prioritize:

- Expenditure rebalancing toward productivity-enhancing and socially efficient categories by eliminating poorly targeted subsidies, particularly energy subsidies, while safeguarding high-quality public investment. Enhancing the targeting and cost-efficiency of social security programs is indispensable to manage demographic pressures without eroding welfare quality.

- Revenue restructuring to strengthen equity and efficiency. Policy options include expanding taxation of financial income for high-income earners, broadening the property-tax base, streamlining income-tax deductions and gradually unifying and raising the consumption-tax rate. Any new deductions, such as the proposed personal-income-tax reforms, should be budget-neutral, supported by compensatory revenues or savings.

- Restricting reliance on supplementary budgets, whose repeated and partial execution dilutes fiscal discipline and transparency. Such budgets should be confined to genuine, unanticipated shocks beyond the scope of automatic stabilizers. Medium-term expenditure commitments, especially in industrial policy and the green transition, must be incorporated into the regular annual budget process.

As domestic interest rates normalize, the cost of servicing public debt is projected to roughly double by 2030, underscoring the urgency of a robust debt-management strategy. With gross financing needs expanding and the Bank of Japan (BoJ)’s balance sheet contracting, sovereign issuance will increasingly depend on renewed demand from foreign investors and domestic institutional holders. This shift in the investor base heightens the importance of maintaining fiscal credibility, as foreign participation tends to be more sensitive to perceived sustainability risks.

IMF perspective and the Takaichi strategy

The IMF’s evolving stance represents a subtle yet significant departure from its pre-pandemic orthodoxy. Rather than advocating procyclical austerity, the Fund now distinguishes between productive fiscal stimulus — which enhances potential output and facilitates structural rebalancing — and generalized expansion, which risks eroding policy credibility and market confidence.

In its working paper, economists Sam Ouliaris and Celine Rochon argue that Japan’s diminished fiscal multipliers stem from the persistent elevation of the debt-to-GDP ratio. Despite historically low interest rates, the accumulation of debt has deepened structural deficits and heightened the likelihood of future fiscal adjustment through higher taxes or expenditure restraint. This dynamic underscores a critical policy constraint: the efficacy of fiscal policy declines as debt-sustainability concerns become endogenous to private-sector expectations.

Consequently, stimulus is most effective when directed toward productivity-enhancing, innovation-driven investment that raises potential output and reinforces fiscal credibility over the medium term — rather than measures that merely boost transitory demand. This interpretation helps reconcile an apparent paradox: While Japan’s borrowing costs remain low, the marginal impact of new stimulus on growth is declining because private agents increasingly expect future consolidation.

In our interpretation of the same paper, we contend that the reduction in multipliers reflects not temporary cyclical weakness but structural saturation — the upward trajectory of government debt relative to GDP. Despite persistently low interest rates, it has expanded Japan’s structural deficit and increased the likelihood of eventual fiscal consolidation through reduced expenditures and higher taxation.

Japan, however, remains in a uniquely permissive financial environment. Exceptionally low government-bond yields, the predominance of domestic debt ownership and deep institutional trust confer an unusual degree of fiscal latitude. Yet, as the IMF warns, such conditions are not inexhaustible; they hinge on continued market confidence in future consolidation and structural reform.

Empirical studies reinforce these structural headwinds. Researchers Jiro Honda and Hiroaki Miyamoto demonstrate that population aging weakens the output effects of fiscal stimulus, as older households exhibit lower consumption multipliers and weaker labor-supply responses. Similarly, at the Baker Institute for Public Policy, economist Russell Green and I argue that Japan’s long-term stagnation stems from entrenched rigidities — persistent deflation, sluggish productivity and delayed institutional reform — that constrain the effectiveness of conventional fiscal responses.

These findings highlight the demographic and institutional limits of demand-side stimulus in an aging economy. These demographic limitations mean that stimulus measures relying heavily on household demand are particularly constrained in their effectiveness, reinforcing the urgency of more targeted, productivity-oriented investment.

Prime Minister Takaichi’s economic program, framed as “responsible and proactive fiscal policy,” thus blends near-term social relief with longer-term strategic investment. Her fiscal package integrates income transfers and energy subsidies with industrial support for semiconductors, defense technologies and innovation ecosystems, combining short-term stabilization with supply-side resilience. This approach partially aligns with the IMF’s three-pillar framework for sustainable fiscal policy:

- Strengthening aggregate demand through expanded social protection,

- Enhancing productivity via targeted public investment and

- Maintaining a credible fiscal anchor to ensure long-term debt sustainability.

Yet the alignment remains partial and fragile. The IMF emphasizes that durable fiscal credibility depends on a medium-term framework explicitly linking current stimulus to future consolidation. Takaichi’s strategy, by contrast, prioritizes growth-first sequencing — the conviction that economic expansion will itself generate the fiscal space necessary for subsequent discipline.

This sequencing creates a logical vulnerability: If growth underperforms, the fiscal anchor does not automatically tighten, leaving consolidation perpetually deferred.

Between resilience and reckoning

This divergence reveals a deeper philosophical tension. The IMF envisions discipline preceding growth; Japan is testing whether growth can restore discipline. Both perspectives seek the same macroeconomic equilibrium — a self-reinforcing cycle of wage growth, investment and productivity — but diverge in temporal logic. The IMF’s caution is grounded in cross-country evidence that prolonged fiscal expansion in high-debt contexts can erode market confidence. Japan’s experiment, however, suggests that with credible institutions and domestically anchored financing, fiscal activism may delay the limits imposed by debt dynamics.

In this sense, the “Japan Approach” is neither a repudiation of IMF orthodoxy nor an uncritical adherence to it. It represents a contextual reinterpretation — fiscal policy as an instrument of national resilience, calibrated to domestic realities yet framed within the Fund’s broader logic of credibility through productivity. Japan’s policy debate epitomizes the central dilemma confronting mature, high-debt democracies: whether fiscal sustainability can be achieved not through retrenchment, but through revitalization.

Absent credible medium-term consolidation and productivity reform, however, Takaichi’s growth-first experiment risks collapsing under its own weight. Should it succeed, it may offer a blueprint for reconciling stimulus with sustainability in advanced economies. If it fails — as structural evidence increasingly suggests — it will reaffirm the IMF’s enduring caution: that even Japan’s exceptional fiscal insulation cannot permanently defy the gravitational pull of debt dynamics.

Beyond Japan: global imbalances and the return of structural asymmetry

The revival of global current-account imbalances has once again become a defining feature of the post-pandemic economy. Despite the cyclical recovery seen across major regions, the world economy continues to exhibit deep structural asymmetries: persistent US deficits, renewed Asian surpluses and increasingly fragmented trade and capital flows. These patterns suggest that global adjustment will not occur spontaneously as the aftershocks of the pandemic dissipate. Instead, they point to enduring distortions in the distribution of savings, investment and demand — distortions that call for deliberate, coordinated policy action.

For economists and policymakers alike, the message is unambiguous: external-sector dynamics must be reintegrated into domestic macroeconomic frameworks. Fiscal sustainability, productivity enhancement, social insurance and financial stability are not discrete policy domains, but mutually reinforcing components of a single adjustment architecture. Neglecting imbalances risks not only abrupt crises, but also prolonged secular stagnation or, in the worst case, a fragmentation of the international monetary system that has underpinned globalization for half a century.

Correcting these imbalances demands more than short-term macroeconomic management — it requires patient, coordinated structural reform rooted in fundamentals rather than expedience. The 2024 BIS Bulletin underscores that trade protectionism and industrial policy realignment act as negative supply shocks, raising prices and depressing investment without materially improving external balances.

Thus, the task of global rebalancing is inherently collective. Surplus economies must expand productive investment and social spending to absorb savings domestically, while deficit economies must rebuild fiscal buffers and national savings without undermining growth. Exchange-rate flexibility can cushion shocks, but only structural reforms in innovation, human capital and infrastructure can sustain adjustment.

Global imbalances have returned, but their structural weight is heavier and their political management more fragile than in the past. The challenge now is to forge a credible and cooperative roadmap that addresses the roots of these distortions, strengthens international institutions and preserves the integrity of the global monetary order anchored by the US dollar. The time for complacency has passed; the window for collective action is narrow but not yet closed.

Japan’s path to resilience

The best prescription for Takaichi is to transform her current stimulus package from a short-lived, demand-support measure into a structured transition strategy designed to rebuild Japan’s fiscal and macro-financial resilience. This requires three mutually reinforcing pillars.

First, fiscal expansion must shift decisively toward targeted, productivity-enhancing investment — in semiconductors, digital infrastructure, human capital and industrial innovation — so that public spending raises potential growth rather than merely cushioning cyclical weakness. Researchers Koji Nakamura, Sohei Kaihatsu and Tomoyuki Yagi demonstrate that Japan’s productivity slowdown stems from two structural frictions: the inefficient utilization of accumulated technologies, capital and labor within firms, and weak reallocation of these resources across firms.

Fiscal policy should therefore prioritize investments that not only strengthen frontier technologies but also enable firms to reorganize production processes, adopt digital tools, upgrade research & development capacity and redeploy labor and capital more flexibly in response to technological and demographic shifts. By anchoring stimulus in areas that enhance both technological capability and resource mobility, Japan increases the likelihood that debt-financed spending today generates durable productivity gains and greater fiscal space tomorrow. This approach aligns with empirical evidence showing that productivity-oriented investment delivers larger long-run multipliers than generalized transfers or subsidies, particularly in aging, high-debt economies.

Second, Takaichi must introduce a simple, credible and binding medium-term fiscal rule that gradually moves the primary balance toward sustainable territory. Establishing such a framework is essential because Japan’s chronic deficits and rising debt burden have weakened long-run fiscal resilience, even as government bond yields have remained artificially low. Researchers Takeo Hoshi and Takatoshi Ito show that Japan’s low Japanese government bond yields are sustained by structural factors — high domestic savings, home bias among institutional investors and stable long-term expectations. Yet they warn that these conditions will erode as the population ages and the investor base contracts.

As demographic aging reduces national savings and risk tolerance, markets may reassess Japan’s fiscal trajectory, making policy credibility and transparency increasingly vital to preventing sudden increases in borrowing costs. A well-designed fiscal rule helps anchor expectations, mitigate concerns about future taxation and inflation and signal a commitment to gradual consolidation without imposing immediate austerity.

This approach is consistent with evidence that Japan’s fiscal policy has historically been insufficiently responsive to rising debt, as well as with international findings that credible fiscal rules can support orderly, growth-friendly consolidation without triggering abrupt austerity. By adopting a transparent and enforceable medium-term anchor, Takaichi can reinforce confidence in Japan’s fiscal management and limit the probability of a sudden rise in borrowing costs as structural conditions evolve.

Third, and most critically, any normalization of monetary policy must be paired with an explicit, institutionally coordinated strategy to resolve zombie firms — the structural legacy of decades of ultra-low interest rates. Researchers Ricardo Caballero, Hoshi and Anil Kashyap illustrate that zombie firms depress investment, productivity and the healthy reallocation of credit by tying up financial, managerial and human resources in inefficient firms that survive due to banks’ evergreening practices. With the BoJ gradually shifting toward a more normal interest-rate environment, these firms represent a major transmission risk: Even modest rate hikes could expose the fragility of heavily indebted, low-productivity firms, prompting bankruptcies, credit contractions and a sharp decline in business investment.

To prevent this outcome, a coordinated policy architecture is essential. The BoJ must adopt a gradual, predictable normalization path; financial regulators should provide targeted flexibility that facilitates restructuring rather than indiscriminate tightening and policymakers must expand programs supporting corporate restructuring, mergers, divestitures and the reallocation of labor and capital to more productive firms. Such an integrated strategy ensures that monetary normalization strengthens the business sector rather than destabilizing it, while accelerating long-delayed structural adjustments necessary to raise long-term productivity and growth potential.

Strategy, not complacency

The reemergence of global current-account imbalances marks not a cyclical deviation but a structural disequilibrium rooted in fiscal fragility and institutional asymmetry. Persistent excess savings in surplus economies and entrenched deficits in others reveal a deeper malfunction in global adjustment mechanisms — where fiscal policy, monetary credibility and capital-market integration have become progressively decoupled.

As economist Ricardo Reis emphasizes, modern macroeconomic equilibrium is sustained by institutions that internalize imperfections: fiscal authorities that anchor expectations, central banks that preserve credibility and financial systems that intermediate risk without distortion. When these stabilizing institutions erode, imbalances do not self-correct; they amplify through feedback loops of mistrust, inflation drift and policy inertia. In this sense, fiscal and monetary credibility have evolved into global public goods — forms of institutional capital whose degradation in one major economy transmits volatility across borders, destabilizing liquidity conditions and constraining the global supply of safe assets.

In particular, when fiscal authorities fail to provide credible medium-term anchors, private agents increase precautionary saving and shorten investment horizons, reinforcing the very imbalances policymakers attempt to correct.

This logic reframes global adjustment as an institutional equilibrium problem, not merely a policy coordination failure. The erosion of credibility in one jurisdiction increases precautionary demand for safe assets, compressing yields and propagating financial fragility elsewhere. Conversely, credible fiscal anchors and independent central banks generate positive externalities, stabilizing expectations and lowering the cost of global liquidity.

Hence, credibility today functions as an endogenous source of international stability, no longer confined within national borders. This point is especially vital for Japan. If domestic fiscal credibility weakens, the resulting rise in precautionary demand for Japanese safe assets could paradoxically depress yields in the short term while increasing long-term sustainability risks.

Correcting these distortions demands strategy, not complacency. Tactical stimulus or ad-hoc tightening cannot restore equilibrium. What Japan needs is patient, coordinated institutional reform that aligns domestic objectives with systemic coherence — strengthening fiscal frameworks, enhancing productivity and renewing the architecture of macro-financial governance. Adjustment, as Reis argues, is a deliberate act of institutional design, rebuilding the trust architecture that allows disequilibria to unwind without crisis.

The challenge before policymakers is therefore both intellectual and operational. To sustain globalization under stress, nations must reconcile short-term flexibility with long-term credibility, viewing fiscal prudence and monetary independence not as opposing doctrines but as complementary pillars of collective resilience.

The central lesson of this new era makes itself clear: Stability will not arise from market self-correction alone but from the credibility of the institutions that govern it — the very institutions that now constitute the world’s most fragile and indispensable public good.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment