Marta Jiménez, a hairdresser in Cuba’s eastern city of Holguín, covered her face with her hands and broke down crying when I asked her about US President Donald Trump’s blockade of the island — especially now that the United States is choking off oil shipments.

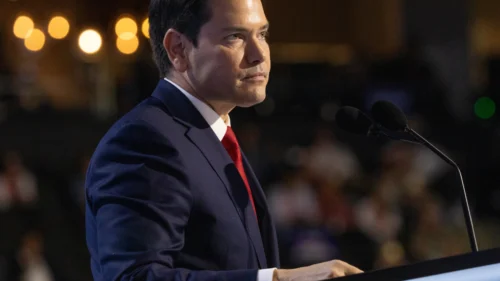

“You can’t imagine how it touches every part of our lives,” she sobbed. “It’s a vicious, all-encompassing spiral downward. With no gasoline, buses don’t run, so we can’t get to work. We have electricity only three to six hours a day. There’s no gas for cooking, so we’re burning wood and charcoal in our apartments. It’s like going back 100 years. The blockade is suffocating us — especially single mothers,” she said, crying into her hands. “And no one is stopping these demons: Trump and Marco Rubio.”

We came to Holguín to deliver 2,500 pounds of lentils, thanks to fundraising by CODEPINK and the Cuban-American group Puentes de Amor. On our last trip, we brought 50-pound bags of powdered milk to the children’s hospital. With Trump now imposing a brutal, medieval siege on the island, this humanitarian aid is more critical than ever. But lentils and milk cannot power a country. What Cubans really need is oil.

Cuban costs

There were no taxis at the airport. We hitchhiked into town on the truck that came to pick up the donations. The road was eerily empty. In the city, there were few gas-powered cars and no buses running, but the streets were full of bicycles, electric motorcycles and three-wheeled electric vehicles used to transport people and goods. Most of the motorcycles — Chinese, Japanese or Korean in manufacture — are shipped in from Panama. With a price tag near $2,000, only those with family abroad sending remittances can afford them.

Thirty-five-year-old Javier Silva gazed longingly at a Yamaha motorcycle parked on the street. “I could never buy one of those on my salary of 4,000 pesos [$166] a month,” he said. With inflation soaring, the dollar now fetches about 480 pesos, making his monthly income worth less than ten dollars.

Cubans don’t pay rent or have mortgages; they own their homes. And while national healthcare has deteriorated badly in recent years because of shortages of medicines and equipment, it remains free. This system is gasping but not abandoned. When my partner, Tighe, had an asthma attack, we went to the clinic and he was breathing in albuterol mist from a nebulizer within minutes. No insurance forms, no bill, just care delivered competently with a smile. That’s what health care looks like when it’s treated as a human right.

The biggest expense for Cubans is food. Markets are stocked, but prices are out of reach — especially for coveted items like pork, chicken and milk. Even tomatoes are now unaffordable for many families.

Holguín was once known as the breadbasket of Cuba because of its rich agricultural land. That reputation took a severe hit last year when Hurricane Melissa tore through the province, destroying vast areas of crops. Replanting and repairing the damage without gasoline for tractors or electricity for irrigation is nearly impossible. Less food means higher prices.

Production across the economy is grinding to a halt. Factories can’t function without electricity, and many skilled workers have given up their state jobs because wages are so low. Jorge, whom I met selling bologna in the market, used to be an engineer at a state enterprise. Verónica, once a teacher, now sells sweets she bakes at home — when the power is on. Ironically, while US Secretary of State Marco Rubio claims he wants to bring capitalism to Cuba, US sanctions are crushing the very private sector that most Cubans now depend on to survive.

Blame and survival

I talked to people on the street who blame the Cuban government for the crisis and openly say they can’t wait for the fall of communism. Young people told me that their goal is to leave the island and live somewhere they can make a decent living. But I didn’t meet a single person who supported the blockade or a US invasion.

“This government is terrible,” said a thin man who changes money on the street — an illegal but tolerated activity. But when I showed him a photo of Rubio, he didn’t hesitate. “That man is the devil. A self-serving, slimy politician who doesn’t give a damn about the Cuban people.”

Others put the blame squarely on the US. They point to the dramatic improvement in their lives after US President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro reached an agreement and Washington eased many sanctions in 2014–2016. “It was the same Cuban government we have now,” one man told me, “but when the US loosened the rope around our necks, we could breathe. If they just left us alone, we could find our own solutions.”

Cubans are only surviving this siege because they help one another. They trade rice for coffee with neighbors. They improvise, saying the phrase, “no hay, pero se resuelve” (“we don’t have much, but we make it work”). The government provides daily meals for the most vulnerable — the elderly, the disabled, mothers with no income — but it becomes harder each day as the state has less food to distribute and less fuel to cook with.

At one feeding center, an elderly volunteer told us he spends hours every day scavenging for firewood. He presented us with a chunk of a wooden pallet, nails and all. “This guarantees tomorrow’s meal,” he stated, his face caught somewhere between pride and sorrow.

Can Cuba endure?

So how long can Cubans hold on as conditions worsen? And what is the endgame?

When I asked people where this is leading, they had no idea. Rubio wants regime change, but no one can explain how that would happen or who would replace the current government. Some speculate a deal could be struck with Trump. “Make Trump the minister of tourism,” a hotel clerk commented, only half-joking. “Give him a hotel and a golf course — a Mar-a-Lago in Varadero — and maybe he’d leave us alone.”

Who will win this demonic game that Trump and Rubio are playing with the lives of eleven million Cubans?

Ernesto, who fixes refrigerators when the power is on, places his bet on the Cuban people. “We’re rebels,” he told me. “We defeated Batista in 1959. We survived the Bay of Pigs. We endured the Special Period when the Soviet Union collapsed, and we were left with nothing. We’ll survive this, too.”

He summed it up with a line Cubans know by heart, from the great songwriter Silvio Rodríguez: “El tiempo está a favor de los pequenos, de los desnudos, de los olvidados” — “Time belongs to the small, the exposed, the forgotten.”

In the long sweep of time, endurance outlasts domination.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment