Standing in the Rose Garden last April, flanked by American flags, US President Donald Trump declared war on free trade. Nine months later, the most striking feature of that declaration is not how much commerce has collapsed, but how quickly it has rerouted. Trade did not stop; it flowed around obstacles. As a DHL Express company executive observed, trade “will find its way” — behaving, in effect, like water flowing around obstacles under high-tariff regimes.

That image of water seeking a new channel captures the first-order reality of the Trump administration’s trade policy. Tariffs have risen sharply, and the costs are landing where economists would expect: higher prices for tariff-sensitive goods, stress on firms reliant on imported inputs, and an implicit tax on households and businesses. Yet the system has adapted. The US is buying less directly from China, but more from Chinese-owned factories operating in lower-tariff jurisdictions such as Vietnam. Mexico has emerged as an unexpected winner. And Beijing’s leverage over rare earth minerals has spurred new efforts to secure alternative supply — an industrial-policy subplot nested inside a tariff story.

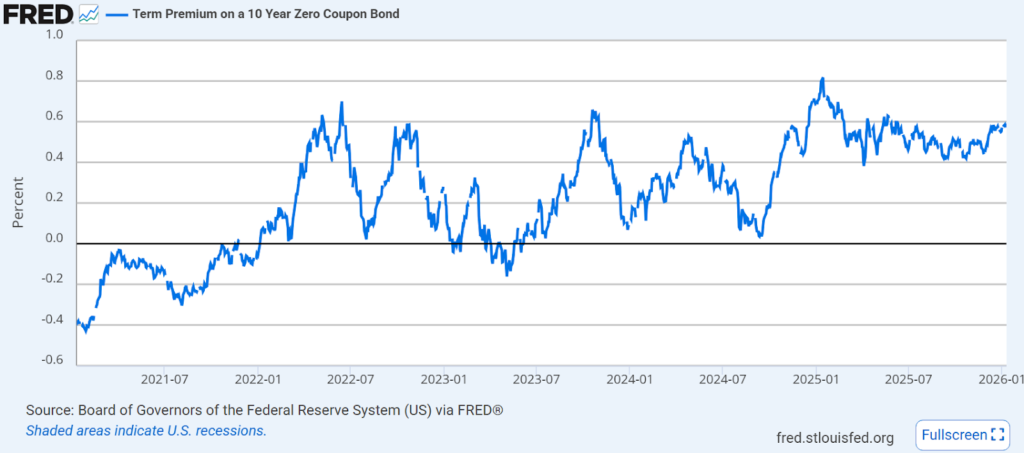

The second-order reality is more subtle: Trade policy uncertainty also influences the US Treasury market through financial market sentiment. Asset-manager commentary from institutions such as BlackRock and Amundi emphasizes that tariff escalation can increase macroeconomic uncertainty, raise bond market volatility and affect term premia. In this environment, investor demand for duration becomes more cautious, implying an indirect but economically meaningful link between trade policy uncertainty and Treasury yields beyond mechanical supply-and-demand effects.

Understanding the Treasury channel requires starting with the obvious, then moving to the consequential. Obviously, tariffs raise revenue. Consequentially, the Treasury market is where America prices its future, and where policy uncertainty becomes a term premium that households and businesses end up paying.

CAPTION: Term premium on a ten-year zero-coupon bond. Via Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

The direct economics: inflation, an implicit tax, and revenue

Tariffs are blunt. When imposed broadly, they raise costs across wide swaths of the economy. A tariff on an imported refrigerator is not just a tax on the foreign producer; it becomes a higher landed cost for the importer, which becomes either a lower profit margin, a higher price for the consumer or a combination of both.

Tariffs can also lift the price of domestic substitutes: If imported steel becomes more expensive, domestic steel producers can raise prices too, even if their cost base didn’t change as much. For consumers, the effect shows up in specific aisles: higher prices for furniture, toys and clothing; higher prices for some foods like beef, bananas and coffee; and price pressures that spread unevenly across regions and income groups.

For firms, tariffs are less a doctrine than a daily problem to be managed. One small but telling example comes from the trade-law trenches. Dan Harris, a Seattle lawyer who recently began working on tariffs, now advises importers on how to legally reduce duty exposure. The methods are not dramatic — restructuring contracts, separating allowable costs, adjusting declared values within the rules — but they absorb time, capital and attention that would otherwise be spent on production or expansion.

This logic repeats across supply chains. A buyer who purchases an injection mold outright avoids embedding that cost in the tariff base of every imported unit. The decision is rational and lawful, yet it underscores a broader pattern: tariffs redirect effort toward avoidance rather than efficiency. The same dynamic appears in Vietnam, where factories have seen sudden order surges as US buyers shift away from China — only to face capacity constraints and renewed uncertainty as tariffs spread. Supply chains adapt, but the adaptation itself is costly, unstable and rarely conducive to long-term productivity growth.

Channel one: treasury supply — deficits, issuance, and tariff “cushions”

The US budget deficit is large by historic standards — 6.2% of GDP in recent readings, roughly double the average pace from 1980 through the pre-Covid-19 pandemic era. Bigger deficits mean more Treasury issuance. If all else is equal, more supply requires either more demand or higher yields to clear the market.

Tariff revenue can, in principle, reduce the borrowing needed at the margin. Customs receipts have risen sharply in the high-tariff world, creating what some policymakers see as a fiscal cushion. But the margin matters: If tariffs generate tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars in annual revenue, that is meaningful — yet it is not transformative against structural deficits driven by entitlement spending and debt service costs.

The more important issue for markets is not just how much tariff revenue is collected, but how reliable that revenue is. Tariff receipts are unusually exposed to legal risk (court challenges to executive tariff authority), negotiation risk (trade deals that reduce rates or carve out exemptions) and macroeconomic risk (recessions or demand shifts that shrink import volumes). As the Bipartisan Policy Center explains, tariff revenue fluctuates with trade policy, legal outcomes and import behavior, making it an inherently volatile source of funding rather than a stable offset to deficits.

That volatility matters because bond markets price expectations and risk, not static arithmetic. Even when tariff revenue rises into the tens or hundreds of billions of dollars, it remains small relative to structural deficits driven by entitlement spending and rising interest costs. PBS NewsHour shows that claims of tariffs meaningfully stabilizing the fiscal outlook break down once the scale of federal spending and borrowing is considered.

Treasury yields therefore respond less to the existence of tariff revenue than to uncertainty around the longer-term fiscal path. When investors believe deficits may widen — because tariff revenue falls short, spending rises faster than expected or borrowing needs surprise to the upside — they demand higher compensation to hold long-dated debt. Because Treasury yields anchor mortgage rates and corporate borrowing costs, that repricing quickly tightens financial conditions across the economy.

Tariffs may reduce borrowing at the margin, but by introducing uncertainty into revenue projections, they can also raise risk premia — offsetting part of the perceived fiscal “cushion.”

Channel two: treasury demand — foreign buyers and trade relationships

If supply is one side of Treasury pricing, demand is the other — and trade policy influences demand most clearly through foreign investor behavior.

Foreign investors hold roughly one-third of the US Treasury market, making their portfolio decisions central to US interest rate dynamics. During periods of tariff escalation, Council on Foreign Relations reports often raise concerns about a potential “sell America” trade, in which foreign official institutions reduce exposure to US assets as trade relationships deteriorate. Historically, however, such fears have rarely materialized in abrupt form. Even during episodes of trade conflict, foreign holdings of Treasuries have often remained stable or increased, reflecting Treasuries’ role as the world’s deepest and most liquid pool of safe collateral. In an environment of global uncertainty, investors typically prioritize liquidity and capital preservation, even when they are uncomfortable with the policy environment generating that uncertainty.

The more relevant risk, therefore, is gradual erosion at the margin. Central banks and sovereign wealth funds rarely engage in headline-grabbing sales. Instead, they can diversify quietly over time by allowing maturing Treasury holdings to roll off and reinvesting incrementally elsewhere. Over years, these slow-moving adjustments can meaningfully affect demand conditions at the margin.

Trade relationships matter in this process. Reserve composition has historically been influenced by trade networks, with countries tending to hold reserves in the currencies of their primary trading partners. If US protectionism leads to sustained shifts in global trade toward alternative hubs, reserve portfolios may adjust gradually in parallel — without a single triggering event, but with cumulative effects over time.

From a market perspective, this distinction holds weight. Treasury demand remains deep and resilient, but it is not immutable. Persistent trade fragmentation can slowly reshape the composition of global reserves, subtly reducing marginal demand for US debt even in the absence of overt selling pressure. Such shifts are easy to overlook in the short term, yet increasingly relevant for long-term rate expectations and term premia.

Channel three: tariffs, inflation, growth and the yield curve

The third channel operates through the macro economy: how tariffs affect inflation and growth, and how those effects are ultimately priced into financial markets.

Tariffs tend to raise prices directly by increasing import costs and indirectly by expanding domestic firms’ pricing power. At the same time, they can weigh on growth by raising input costs, disrupting supply chains and provoking retaliation. The resulting combination, higher inflation risk alongside weaker or more uncertain growth, is precisely the configuration that markets associate with elevated macro risk rather than a straightforward demand slowdown.

Markets typically express this tension through the yield curve. When investors believe tariffs will push up near-term inflation while clouding the longer-term outlook for growth, productivity and policy stability, longer-dated yields can rise even as growth expectations soften. This reflects the role of term premia. The long end of the curve is not simply a forecast of future short rates; it also embeds compensation for inflation volatility, fiscal uncertainty and policy risk.

Recent market behavior reinforces this interpretation. Gold prices have continued to rise even as US yields remain elevated, signaling that higher yields are no longer being read as a clean indicator of safety. Instead, both gold prices and long-term Treasury yields appear to be responding to the same underlying force: a rise in uncertainty and risk premia. When yields increase because investors demand additional compensation for fiscal, geopolitical and policy risk — rather than because growth prospects are improving — the opportunity cost of holding gold becomes less binding. In that sense, gold is not competing with Treasuries on yield, but reacting to doubts about their reliability as the world’s unquestioned safe asset.

Geopolitical shocks can accelerate this dynamic. Recent US military actions involving Venezuela briefly pushed gold prices higher, not because they altered global trade flows in a material way, but because they reinforced perceptions of geopolitical fragility layered on top of trade and fiscal uncertainty. Such episodes matter less for their direct economic impact than for what they reveal about market psychology: When policy and geopolitical risks stack, investors demand protection that sits outside sovereign balance sheets.

This framework helps explain why JP Morgan’s bullish outlook for gold remains intact even without aggressive Federal Reserve (or Fed) easing. As long as term premia stay elevated, central banks continue to diversify reserves and geopolitical flashpoints remain unresolved, higher US yields do not suppress gold prices. Instead, they reinforce incentives to diversify away from US financial assets altogether. In that sense, gold’s rise toward $5,000 per ounce by late 2026 would not represent an anomaly driven by temporary fear, but a new equilibrium consistent with a more fragmented and risk-conscious global financial system.

The implications extend beyond gold. The same uncertainty that lifts demand for alternative stores of value also pushes up term premia in the Treasury market. Long-term yields rise not in anticipation of stronger growth, but as compensation for volatility and unpredictability. That repricing feeds directly into higher borrowing costs across the economy, tightening financial conditions even when the underlying trade shock itself appears manageable.

For households and firms, this channel is where trade policy becomes tangible. The ten-year Treasury yield anchors borrowing costs across the economy, including mortgage rates, auto loans and corporate financing. If tariffs contribute to persistently higher term premia, it results in a durable tightening of financial conditions, often outweighing any localized employment gains associated with reshoring or import substitution.

Higher yields also feed back into public finances. Rising interest rates increase government debt service costs, tightening the fiscal constraint and reinforcing deficit dynamics over time. What begins as a trade policy shock can therefore reappear as a budgetary one, amplifying longer-term sustainability concerns.

Globally, higher US yields tend to transmit tighter financial conditions abroad through capital flows and exchange rate pressures, increasing stress in more vulnerable economies. In that sense, the macro consequences of tariffs are not confined to domestic prices or output; they propagate through global financial channels.

For these reasons, Treasury yields are not merely an economic statistic. They are a strategic price — summarizing how trade policy, inflation risk, fiscal dynamics and global financial conditions intersect in real time.

Trade is like water… but it hides risks

The industry stories from the tariff era are familiar by now: lawyers building compliance playbooks, factories booming in Vietnam, Mexico benefiting from trade diversion, grocery importers cancelling shipments, governments accelerating rare earth strategies. Together, they reinforce the comforting saying that trade behaves like water: Block one channel and it simply flows around the obstacle.

That metaphor is only half true. Trade does reroute. The world does not stop trading because one country raises tariffs. But rerouting is not costless.

It can be inflationary, as supply chains move to higher-cost locations. It can lower productivity by fragmenting production networks built for efficiency. It can shift bargaining power across firms, workers and countries. And most importantly for markets, it raises uncertainty.

In financial markets, uncertainty comes with a price. In the Treasury market, it appears as a higher term premium — the extra return investors demand to hold long-dated US debt when the economic and policy outlook feels less predictable. That premium does not stay in the bond market. It is transmitted directly into mortgage rates, corporate financing costs and global capital flows.

Because US Treasuries are the benchmark asset of the global financial system, changes in their pricing ripple outward. What begins as a trade policy shock can become a broad tightening of financial conditions, shaping investment decisions at home and exporting stress abroad.

This is where trade policy becomes strategic. As economists Emmanuel Farhi and Matteo Maggiori argue in their model of the international monetary system, the global role of US debt rests on credibility — the belief that American public liabilities are safe, liquid and insulated from short-term political shocks. That credibility allows the United States to borrow cheaply and at scale.

Paradoxically, a policy framed as strengthening national power, if mishandled, can weaken the foundation of that power. Tariffs may redirect trade. But if they also raise uncertainty and risk premia, they can quietly erode the credibility and attractiveness of US debt — the asset on which American economic power ultimately rests.

The trade war’s hidden front is the bond market

The trade war has not broken global commerce but redirected it. Firms and countries are adapting quickly — routing around tariffs, shifting production footprints, building new compliance strategies and rebalancing trade relationships. That adaptability is real and will likely persist.

But adaptation carries costs, and the most important costs may not appear on a customs receipt. They may appear as a higher term premium in the Treasury market — a subtle repricing of US policy uncertainty that raises borrowing costs for households, businesses and the federal government itself.

This year and beyond, the most strategic way to think about tariffs is as a variable that interacts with Treasury supply, Treasury demand and the Fed’s inflation calculus. A trade policy that treats the Treasury market as an afterthought risks turning a tariff shock into a bond shock. In an economy built on the benchmark of US yields, a bond shock becomes everyone’s problem.

If “trade is like water,” then Treasuries are the riverbed. Policy can redirect the flow, but if it erodes the bed, the flood will not stay contained.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment