Populism has reemerged as a central force in the global political economy, disrupting longstanding assumptions about economic governance, institutional design and democratic accountability. Though rooted in diverse ideological traditions, contemporary populist movements, from the nationalist right in Europe and the United States to redistributionist regimes in Latin America, share a common logic: They reject pluralism in favor of a singular interpretation of the “people’s will.”

The conceptual complexity of populism

While people often use the term “populism” interchangeably with anti-elitism or demagoguery, rigorous conceptual definitions focus on its ideational structure. As historian Jan-Werner Müller argues, populism frames politics as a moral battle between a homogeneous, virtuous “people” and a corrupt elite. Anti-pluralist logic serves as its key feature; this belief opines that only the populist leader represents the authentic will of the people, rendering opposition illegitimate.

This framework allows populism to transcend traditional left–right divides. Latin America has seen left-wing populism oriented toward redistribution and anti-corporate rhetoric, while right-wing populists in Europe and the US focus on immigration, identity and national sovereignty. Despite divergent policy preferences, their common mode of governance — centralizing power, delegitimizing institutions and polarizing society — creates systemic challenges for democratic capitalism.

As Harvard University economist Dani Rodrik suggests, not all populist regimes are identical. They differ in whether they challenge political norms, economic orthodoxy or both. This yields a fourfold typology:

| Political Sphere | Economic Sphere | Regime Type | Examples |

| Constrained | Constrained | Liberal technocracy | European Union |

| Unconstrained | Constrained | Political populism only | Hungary (under Viktor Orbán) |

| Constrained | Unconstrained | Economic populism only | Ecuador, Argentina |

| Unconstrained | Unconstrained | Authoritarian populism | Russia, Turkey,Venezuela |

This typology helps explain divergent trajectories. Some regimes (e.g., Hungary) maintain macroeconomic discipline but erode political checks, while others (e.g., Venezuela) collapse under the weight of both economic mismanagement and democratic backsliding.

A quantitative lens

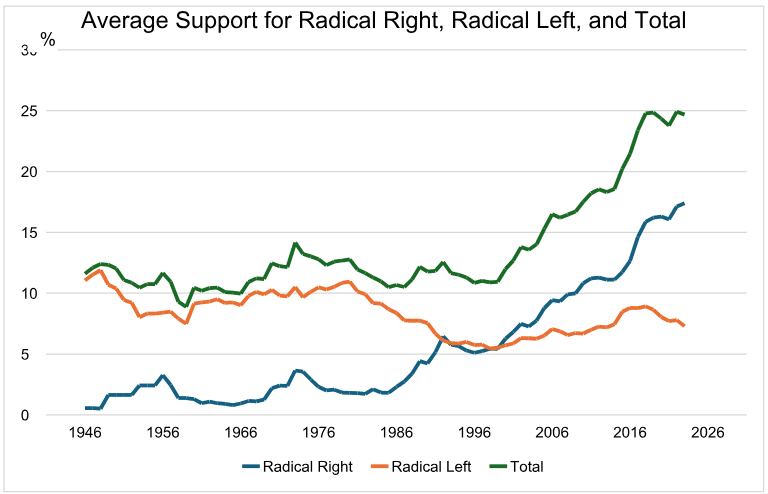

To capture the global proliferation of populism, researchers have developed metrics such as the Authoritarian Populism Index, introduced in 2016. This index quantifies the electoral strength of parties that demonstrate key populist characteristics — anti-elitism, anti-pluralism, nationalism and illiberalism — based on content analysis of manifestos, speeches and governance records.

The index acts as a barometer of democratic stress and reflects the increasing appeal of anti-institutional politics in response to perceived failures of technocratic governance. Its persistently elevated readings suggest that populism is not an episodic deviation, but a structural realignment in political demand.

Electoral backing for national conservative parties has followed an upward trajectory since 1990 and remains robust today. As of now, average support stands at 13.9% — only marginally lower than the 14.1% recorded in 2022. While public alignment with right-wing authoritarian or populist movements continues to strengthen, support for radical left parties has been on a consistent downward trend in recent years.

Populism and macroeconomic policy

Populism’s economic consequences show most clearly when viewed through the lens of “macroeconomic populism,” a term coined by economists Rüdiger Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards. This type of economic populism prioritizes rapid growth, redistribution and nominal wage increases while downplaying inflation, budget constraints and institutional credibility. Case studies from Latin America, such as President Salvador Allende’s Chile or President Alan García’s Peru, illustrate the recurring pattern: initial enthusiasm followed by macroeconomic instability, capital flight and ultimately economic collapse.

More recent empirical work by Kiel University members Manuel Funke, Moritz Schularick and Christoph Trebesch reinforces these concerns. Using a long-run cross-country dataset, they reveal that 15 years after a populist leader takes power, a country’s GDP per capita is, on average, 10% lower than it would have been under a non-populist regime. These outcomes are not due to ideology alone, but the erosion of institutions and economic policy discipline that populist governance typically entails.

Economists have historically favored the delegation of policy authority to independent institutions — central banks, regulatory agencies or international rules — as a safeguard against short-termism and political opportunism. Populists often view such constraints as illegitimate, arguing that they stifle the will of “the people.” This leads to the rejection of technocratic norms, discretionary fiscal excess and confrontational trade policy, all of which may produce near-term political gains but exact long-term economic costs.

Four pillars of populist constraint

In his July 2025 remarks at the Center for Strategic and International Studies-hosted event “Rebalancing and Reform: Betting on America,” World Bank Chief Economist Indermit Gill offered a prescient warning: Populism is not merely a political style or episodic reaction — it is a structural constraint on reform. Especially in an era of rising inequality, political mistrust and global fragmentation, populism impairs the credibility and functionality of institutions vital to long-term development.

Gill identified four pillars of populist constraint, which are:

- Populism as a structural constraint

Populism delegitimizes technocratic reform by portraying it as a betrayal of national sovereignty or elite collusion. Structural policies — such as pension reform, subsidy rationalization or trade liberalization — are rebranded as “anti-people,” making evidence-based policymaking politically toxic.

- Institutional bypass and hollowing

Populist leaders often undermine or circumvent institutions like central banks, anti-corruption agencies and statistical bureaus. The erosion of institutional autonomy reduces policy credibility, deters investment and accelerates clientelism and discretionary spending.

- Erosion of global cooperation

Populist governance amplifies distrust in international institutions (e.g., International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization) and often embraces protectionism and economic nationalism. These tendencies exacerbate global imbalances and reduce the scope for coordinated responses to shared challenges like climate change or pandemics.

- Technology as a limited counterweight

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, green energy, biotechnology and advanced communications (e.g., 5G) hold transformative potential, especially for developing economies. These innovations offer tools for accelerating growth, improving public service delivery and addressing systemic challenges like climate change. However, technological advancement alone cannot substitute for institutional resilience. In the absence of transparent, accountable governance, such technologies risk exacerbating inequality, reinforcing authoritarian control or being co-opted for political gain. Institutional integrity remains a prerequisite for ensuring that innovation contributes to inclusive and sustainable development.

Toward post-populist reform

We cannot overcome populism through elite denunciation or technocratic assertion alone. If it emerges from genuine grievances — economic marginalization, institutional dysfunction or democratic alienation — then the response must be substantive, not rhetorical. The political center must evolve to offer not just stability, but responsiveness and reform.

Economically, we must recalibrate market-oriented policies to address structural inequalities, stagnant mobility and regional disparities. Politically, we must embrace a renewed commitment to pluralism, institutional transparency and democratic norms — including the legitimacy of opposition, the peaceful transfer of power and the rule of law.

Economists and policymakers should not simply critique populism, but design policy architectures that are both inclusive and durable — policies that restore trust, deliver shared prosperity and reflect the lived realities of those left behind. In this respect, overcoming populism is less about countering its leaders and more about fulfilling the democratic and economic promises that have too often gone unmet.

Our goal is not to suppress populism, but render it obsolete. That requires addressing the failures — economic insecurity, democratic disillusionment and institutional erosion — that fuel its rise. A forward-looking agenda must make liberal democracy not only defensible in theory but effective in practice: capable of delivering dignity, accountability and opportunity to all. Only by bridging the gap between democratic ideals and lived experience can we build a political economy resilient enough to transcend the populist moment.

[Lee Thompson-Kolar edited this piece.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 3,000+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment