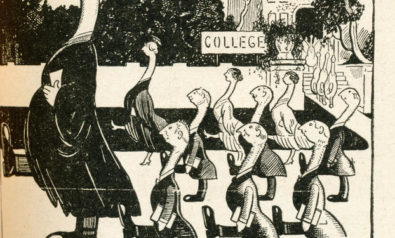

Free for all, free for all. Can top universities provide premium caliber education at no cost to the student?

Providing free, high-quality education to all may seem like an impossible ideal, but several elite institutions are betting that it is an idea whose time has come. Several aspects of free online education have already been given proof-of-concept: The University of Phoenix has demonstrated the viability of online eduction, albeit at a premium price. The popularity of Technology Entertainment Design (TED) Talks has shown that there is a mass audience for academic-style presentations. The Khan Academy has received support from many large foundations for its ability to provide basic education free through streaming videos. The question is, can these models be merged to provide a high caliber of university education at no cost to students? Powerful people are saying yes.

Three major players have entered the market early in the game, each with a slightly different strategy. Sebastian Thun, the man behind Google’s driverless car, left Stanford to establish Silicon Valley start-up Udacity. Then there is Coursera, headed up by Stanford University itself, which is also for-profit. Finally, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard have joined together to form the non-profit EdX. Excitement is running high over these projects. A coup at the University of Virginia (UVA) ended with the dismissal of its president, in part because she had not jumped on the free education bandwagon. She has since been reinstated – and UVA immediately joined Coursera. Other top universities have been lining up to join them; Coursera now boasts thirty-three, while EdX has turned away everyone but Berkeley. Yet it remains to be seen whether there is sufficient demand, adequate technology or long-term funding to support any model of free university-level education.

Sources of Demand

Pilot programs suggest that there will be no problem finding demand for elite post-secondary training. EdX’s March 2012 offering of Circuits and Electronics boasted an enrollment of hundreds of thousands. Early offerings by rivals Coursera and Udacity also attracted substantial numbers of students. However, these initial numbers cannot be extrapolated to later courses. Most early classes have been in the fields most likely to attract online attention – computer science and engineering. More importantly, pioneering professors like Sebastian Thrun or MIT’s Anant Agarwal are likely to be compelling instructors. It is far from clear that courses in other disciplines taught by a second wave of professors will attract as much attention.

Nonetheless, a general survey of market conditions indicates that there should be little problem finding an audience for free university eduction. In the United States and in Western Europe, tuition fees have risen faster than student willingness or ability to pay them. These students are a prime audience for free versions of university courses, even if they offer a lower level of certification. The rapid expansion of internet access in the developing world offers an even bigger potential market. In the past decade, countries like China, Brazil and Russia have seen the portion of their populations using the internet grow from 2% to 35-40%. Other large countries such as India and Indonesia have seen smaller but significant increases in the number of internet users. These countries also experience exceptionally intense competition to attend their elite universities. Free education initiatives are speculating that these massive untapped markets will provide hundreds of thousands, or even millions of customers for brand-name American education.

The Challenges of Structuring Online Education

The basic structure of online courses is the same as most university offerings, but with technology replacing teaching staff. Lectures are provided through streaming video, discussion sections occur on message boards, and problem sets are graded automatically. Each of these innovations has benefits and costs. Videos can be paused and re-watched if students miss a point, but the lecturer does not have the ability to respond to the student in realtime. Message boards are easily extensible without the cost of hiring teaching assistants, but they are also easily dominated by a few unregulated individuals. Most problematically, there are limits on what can be automatically graded. It is at this point that free online courses differentiate with high-priced versions, most of which hire teaching assistants and markers. Automatic grading has moved from an infancy of multiple choice to a difficult adolescence. Mathematics, science or language questions can have one right answer, and have long been automated; but questions in the humanities and social sciences are hard to evaluate as simply as "true" or "false". Even if there is a single correct response, there is the difficulty of assessing process – students may have arrived at the correct result through an incorrect or inefficient workflow. In computer science, student programs are now tested with multiple inputs to assess both their correctness and efficiency, but this system remains fairly inaccurate and is not yet possible in other disciplines.

Udacity, Coursera and EdX are all experimenting with crowd-sourcing as a solution to the assessment problem, but this offers its own challenges and limitations. Group-mediated message boards are one entrée into the potentials of the crowd; they allow and encourage participants to promote or demote questions and answers. Coursera and EdX are both considering having students read and rate their peers’ essays, but this is an even more unreliable process. Universities dedicate substantial resources to train Teaching Assistants to assess essays for argumentation and citation as well as content and use of language. It is unlikely that untrained participants would be able to provide a fair set of assessments. To this point, grading has been the limiting factor preventing the shift from expensive online courses that reach a few students to free online courses that reach thousands.

The critical question in determining the long-term viability of these courses is how they will fund themselves. No cost to students certainly does not mean no cost to universities. Udacity is most explicit about its funding model. It plans to educate students in computer-related areas, and then sell companies access to its newly-trained programmers. This seems like a winning business concept, but only for concrete and in-demand technical skills; it seems unlikely that many companies would pay for online-certified Proust scholars, especially when there are so many unemployed humanists with Ivy League diplomas. There are signs that free courses may provide other avenues for monetization. Despite offering a free version online, EdX’s Circuits and Electronics course prompted a world-wide run on its textbook – selling out all editions in all languages. The recent popularity of “free-to-play” games, where you play for free, but pay for upgrades, suggests the possibility of a similar model of free courses, with premium options like direct access to teaching staff or more “official” certification. There are also fringe benefits such as promoting a school’s “brand”, but without an inflow of capital, it seems unlikely that free courses will be supported by institutions in the long term. Ultimately, time will tell what solutions universities – and the market – are willing and able to support in the long term.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment