Siraj Davis compares the lives of Iraqi refugees in Syria and Jordan in a report, which ultimately indicates that the UNHCR and IOM still have a lot of work to do. Download the full report here.

Background

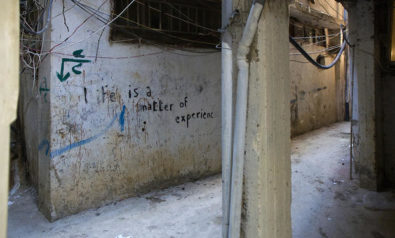

The following is an executive summary from a report involving interviews with Iraqi refugees in Jaramana, Syria and Hashemi Shemali, Jordan. It is not inundated with data but instead presents personal insight into the real-life stories behind the didactic statistics that are normally accumulated to depict lives of refugees. The investigation provides a few personal accounts of the ineffable tragedy Iraqi refugees have endured while simultaneously providing a conduit for all refugees’ complaints from Syria and Jordan.

There are a few imperious cases in Syria and Jordan which caught my attention. These examples represent what I found to be severe exemplifications of the harsh tribulations of Iraqi refugee life. I admit there are other cases which are worse but they were ignored because the pathway of their files seemed positive; the time length of waiting for relocation was not as considerable; the procedures and the conditions they endured did not seem as antagonizing; their stories were already published by other media; it was not easy to verify their stories; or they chose not to participate. Nevertheless, the ensuing examples allow enough detail to accomplish the objective of illustrating some of the major concerns regarding displaced Iraqis’ lives.

Case Studies in Syria and Jordan

In Jaramana, Syria, a single woman by the name of Umm Sandra Alan struggles to hold together a family comprising of an elderly sick aunt and her cat Sherry. She receives only 5,000 Liras from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), to pay a monthly apartment rent of 10,000 Liras. After her father recently died, she has no reason to return to Iraq and is inhibited to visit her aunt in Egypt by the Egyptian government. She works tirelessly at a salon for a mere 3 Liras per day. Her sick aunt comments about Umm Sandra Alan’s future, while being interrupted by her niece’s infuriated, yet innocuous, demands for her to be silent: “I want her to go, to be happy. I don’t want her [to] stay for me. Sometimes [I think it] is better if I died.” Umm Sandra Alan feels the UNHCR does not consider single females’ tribulations in the allocation of aid to Iraqi refugees.

In Jaramana, the kind and intelligent Iraqi refugee, Abu Adezar, struggles against severely deteriorating health while simultaneously waiting for his and his wife’s American visa. They had already been approved for travel to the US three years ago. A former oil engineer in Iraq under US occupation, he fears his return to the country will mark certain death by malevolent groups who may target him for perceived collaboration with the American forces. Abu Adezar’s mother, who is a US citizen, calls often, waiting to be reunited with him. When asked what he wants to say to the audience, he replies, “I want rights and a decent life. I can’t get it in my own country or here. I am not sure I will get them before I die. Do you want me to live without having what was taken from me? Is this the promise Americans told me of in Iraq before I had to run away for my life?”

In Jordan, Abu Omar resides, having fled Iraq in 1997 before the war. He waited until 2006 to finally be approved for relocation to another country; his total length of time residing in Jordan is 15 years. He lives on a limited income of 160 Jordanian Dinars with his wife and daughter, yet his medication costs 90 Jordanian Dinars. Abu Omar is lucky that a grassroots organization called Women’s Federation for World Peace has been helping him to pay for his medication and his daughter’s school expenses. His return to Iraq seems a dismal hope as his brother was kidnapped in Baghdad and is still missing, his aunt’s two sons have been killed, and his brother’s son was assumed dead for three years until appearing one day with both hands broken. This torment over the loss of family does not only affect him, but his wife too. His wife’s aunt and her aunt’s cousin and son were murdered in Baghdad. While waiting longer for relocation to a western country, his most apparent pain is the hardships his daughter has to endure. In regards to returning to Iraq, he retorts with a quick “no.”

Another refugee named Abu Saad, shares the life in Hashemi Shemali with Abu Omar. He has a son, a daughter, and wife who live with him. He left Iraq after his brother was kidnapped and his son threatened by affiliates of Al-Qaeda. His application for relocation to another country was accepted for consideration by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 2006. Despite having family members who are citizens in America, the UK, Australia, and Sweden, Abu Saad was unfortunately rejected by the IOM and UNHCR for resettlement in all western countries on October 6, 2011. After asking what to do next, he was told by a representative at the IOM to apply for a visa at any embassy in Jordan. He has no aid nor hope for relocation so he lingers with his family in Jordan, terrified of what will happen if they are deported back to Iraq.

Abu Amer is an Iraqi refugee in Hashemi Shemali that has been through trauma with the UNHCR in his process of awaiting relocation to the UK. He and his sick wife left Iraq after being threatened by the armed militias: the Sunni Jihad Army and the Shi’a Al-Mahdi army. His two sons, his daughter, and seven nephews are citizens of the UK. He registered with the UNHCR on August 26, 2007 and since then has been told several times by the UN agency that he would travel in a short time (such as within fifteen days). Each time has turned into a nightmare of waiting longer. His twenty filed complaints to the UNHCR including a sixteen page diatribe to the manager, have been answered with no responses — only a verbal altercation with a clerk at the agency. He is now still waiting for the elusive UK visa by the UNHCR.

There are other cases worth mentioning. One Iraqi refugee named Ali, was falsely accused of a lewd act against a minor and incarcerated. He used his passport for collateral in order to secure bail money. When he went to trial, he was found not guilty. The National Center of Human Rights and an independent lawyer in Jordan confirmed that the courts revealed that the plaintiff had used a false testimony against Ali. He is still without the financial means to ascertain his passport.

Another Iraqi refugee by the name of Raja was sent to the US to live in Boston, Massachusetts only to be returned to Hashemi Shemali, Jordan because it was discovered on her records that she was listed as a man.

Common Complaints

Traveling and residing with Iraqi refugees in Syria and Jordan provokes a plethora of testimonies that share synonymous problems which aggravate their lives. There are slight, but insignificant differences. It is important to consider the similarities in order to understand this social issue, consequently improving these lives.

The complaints by Iraqi refugees indicate that they feel the application process is flawed or corrupt. For example, Umm Sandra Alan asserts that her interviewer at the IOM hinted or suggested to her answers that seemed to imply Muslim against Christian violence or to purport that Saddam Hussein was a tyrant. When questioned repeatedly over a long duration of time about her certainty in regards to her negative responses to questions, Umm Sandra Alan replied “I am not going to lie.” Her interviewer retorted, “I am trying to help you go to America.”

Umm Sandra Alan, an Iraqi Christian refugee, stands by her testimony that she chose to be without guile instead of sacrificing her principles for fabricated freedom. Nevertheless, from Syria to Jordan there is a prevalent adage amongst Iraqi refugees that “those who lie, go… [and those] that tell the truth, stay.”

Corruption within the IOM and UNHCR is also another complaint. An Iraqi refugee in Syria named Abu Sabahprovides names of high ranking officials who accept bribes to push their relocation cases. Ironically, Abu Sabah was relocated after our interview much earlier than other refugees who have waited longer and with harsher backgrounds. Many other refugees, from Syria to Jordan, have stated that a couple thousand American dollars can purchase a visa from certain embassies. Moreover, an independent, discreet, and unfinished probe has revealed lower level collaboration in offers of relocation for money. The current status of this probe is that it is extremely difficult to penetrate the top levels of such fraud and also counterproductive to expose by risking splashes in the water from reeling in minnows, consequently scaring off the elusive and larger bass.

The UNHCR monetary aid to Iraqi refugees is also a set allocation despite rising prices. This has exacerbated the ability of refugees to survive. Worse, it has also augmented the number of refugees working illegally, consequently augmenting cases of abuse by employers. Xenophobia against Iraqi refugees has also proliferated as a result of refugees’ rising competition in a floundering job market, positions in schools, and migration into cheaper yet squalid neighborhoods. Ultimately, the limited nature of aid results in the former middle class of Iraq living like beggars.

Refugees also complain that the service and attention to each of their cases by the UNHCR and IOM are deplorable. They assert that both the UNHCR and IOM are lethargic in feedback, inattentive to details that may vet dishonest cases, and slow in processing files. Some refugees in Jordan went to such an extent as to state that if there is an interview with either the IOM or UNHCR on Tuesday, you are likely rejected and if on Saturday, you are accepted. The aforementioned exacerbates the stress refugees live through.

Immigration restrictions by governments where Iraqi refugees reside also prevent them from visiting family in neighboring countries. They are coerced to travel to Baghdad to risk danger and ascertain a visa from an embassy there. The reason for this impediment is countries want to deter growing refugee populations in their country by preventing overstays of visas.

For example, one refugee named Jenan in Jordan has a sister in Syria she has not seen for many years. She points towards her young children during our interview saying, “they have never met their aunt in their lives.” The fear of death in Iraq and lack of mobility is the equivalent of making their country of refuge a prison.

Although some scholars have stated that grassroots organizations fail in distributing aid in an egalitarian way because of a lack of resources, Iraqi refugees complain that some grassroots organizations do not distribute aid equally because of favoritism towards a select few that the organization’s heads have built close relationships with. From Syria to Jordan, many refugees in worse situations than those refugees intimately involved with grassroots organizations, have never heard of some of these organizations.

I witnessed at the Collateral Repair Project funded party in Jordan with a plethora of food and drinks, a decrepit female Iraqi with two bedraggled children arrive at the front door in a desperate state asking for succor. Yet, she was turned away by the head undeterred by the fact that this family had no food or nowhere to stay that night.

There are exceptions of course. Abu Omar, noted earlier in this article, states that out of all the organizations in Hashemi Shemali, the only one that served him objectively and consistently was the Women’s Federation for World Peace. Another refugee named, Abu Ahmad, concurs by dismissing some of the other grassroots organizations as “club house activities and cult like.”

Conclusion

The UNHCR, IOM, and grassroots organizations have provided minimal relief that does not suffice in securing the physical and mental welfare of Iraqi refugees. Worse, there are many instances of malpractice by these organizations which have exacerbated the lives of refugees.

Iraqi refugees need more financial aid. The lack of this aid has caused them to risk their own welfare via illegal employment in order to survive. In addition, the Iraqi refugees in Jaramana and Hashemi Shemali are living in penury without the security of affording education for their children.

These refugees also need rights or a status in a country. The lack of rights experienced in Jaramana and Hashemi Shemali compounds the issue of illegal employment by Iraqi refugees and consequent deportation or imprisonment. Finally Iraqi refugees need more efficient and organized aid agencies with more integrity.

Author’s Note

The devastation brought to these refugees’ nation has created a humanitarian crisis without an adequate response. When I ask Abu Omar about how people can help Iraqi refugees, his terse response was, “feel with us.”

I know what he means now after painful reminiscence from the plethora of stories I have collected. These souls sometimes feel they are the walking dead. I also understand their pessimism for every person who attempts to help them.

I am reminded every time I interview these beautiful, proud, resourceful, intelligent, and kind humans, of a famous poem by Edgar Allen Poe. All of the questions by interviewers are nothing more than the same repetitious raven squawking “nevermore” in the ears of an enervated people who languish because they have lost the life they loved in Iraq, their own Leonor.

Download the full report here.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.

Support Fair Observer

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

For more than 10 years, Fair Observer has been free, fair and independent. No billionaire owns us, no advertisers control us. We are a reader-supported nonprofit. Unlike many other publications, we keep our content free for readers regardless of where they live or whether they can afford to pay. We have no paywalls and no ads.

In the post-truth era of fake news, echo chambers and filter bubbles, we publish a plurality of perspectives from around the world. Anyone can publish with us, but everyone goes through a rigorous editorial process. So, you get fact-checked, well-reasoned content instead of noise.

We publish 2,500+ voices from 90+ countries. We also conduct education and training programs

on subjects ranging from digital media and journalism to writing and critical thinking. This

doesn’t come cheap. Servers, editors, trainers and web developers cost

money.

Please consider supporting us on a regular basis as a recurring donor or a

sustaining member.

Will you support FO’s journalism?

We rely on your support for our independence, diversity and quality.

Comment